March school reopenings: how safe would teachers be?

Schools could start to return to full face-to-face teaching from 8 March.

The plan, outlined by prime minister Boris Johnson, was made alongside a declaration - once again - that “schools are safe”.

He added to this by saying that while schools “bring communities together” and “large numbers of kids are a considerable vector of transmission”, there is no “particular extra risk to those involved in education”.

This is a stance many in education would take umbrage with. After all, the issue of how safe teachers are when working in school is something that remains unanswered - despite it being one of the key questions asked ever since the pandemic began.

As teachers have repeatedly said, much of what is recommended in schools to keep staff and pupils safe is not possible: social distancing - particularly in primary - is extremely difficult, ventilation in old buildings is complex and protocols around drop-offs and pick-ups are tricky to manage.

As such, staff have felt incredibly vulnerable, particularly when schools were teaching 30 children in the same classroom for six hours. Going back on 8 March, even with millions of people vaccinated, will probably not change these feelings for many.

Certainly, the teaching unions have attempted over the past year to demonstrate the dangers. The NASUWT claimed that teacher Covid rates were 333 per cent higher than average; the NEU raised the fact that pupils were those with the highest infection rates during a period of 2020; and a joint statement from a number of unions also warned that January school openings put staff at “serious risk” of infection.

The government, though, has insisted the risk is low: teachers were told in August that they had ”no increased Covid death risk” compared with other workers, while Boris Johnson declared “schools are safe” at the end of last year, before sending everyone back for one day before implementing lockdown.

Coronavirus: the risk to teachers

This back and forth has continued without much conclusive data to underpin either side’s claim.

However, earlier this week, a new Office for National Statistics (ONS) release arrived to offer some insight into what we know from 2020 about the numbers of teachers who sadly died from Covid-19.

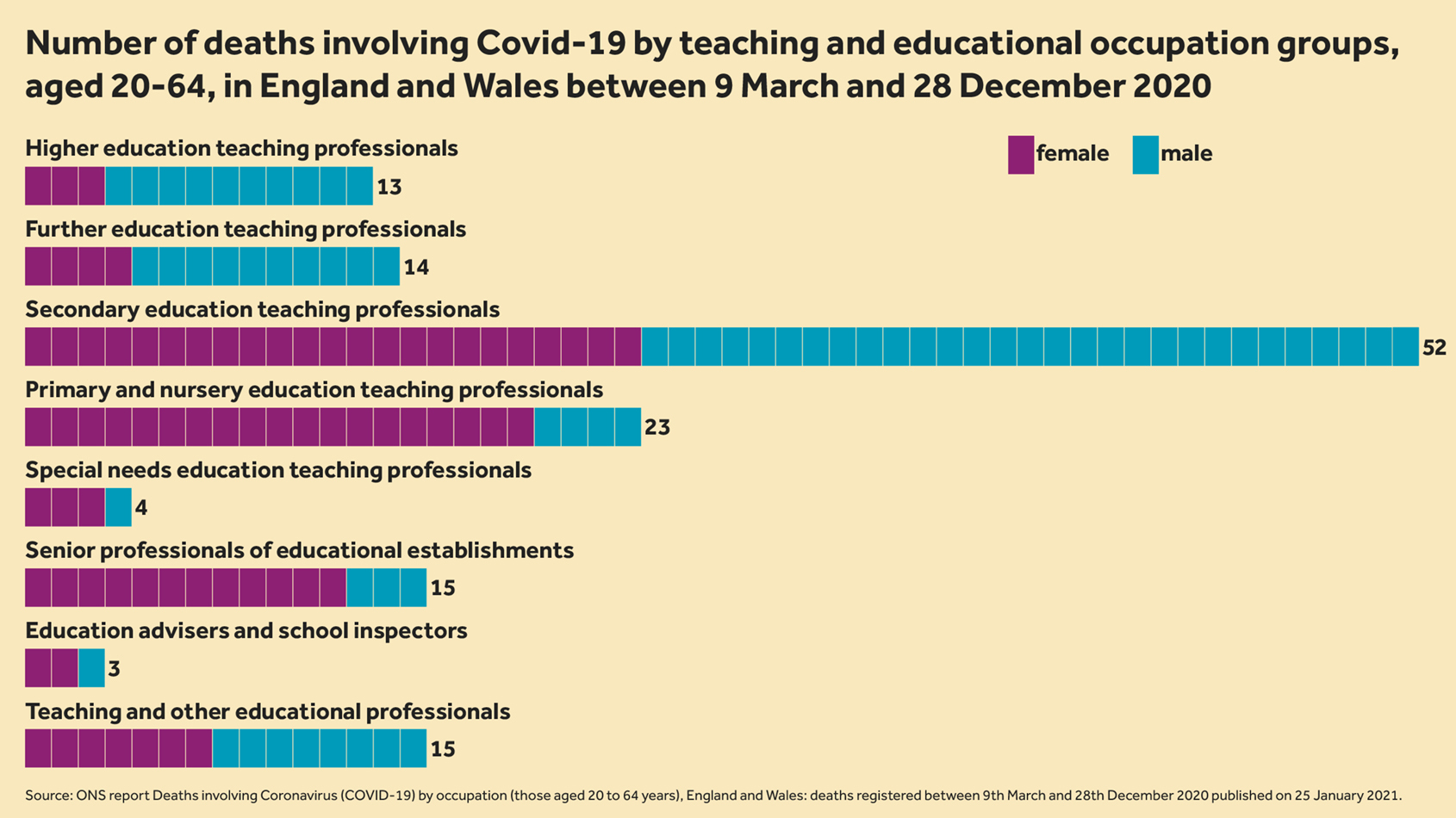

The key fact that the report leads on for the education profession is as follows: between 9 March and 28 December 2020, there were 139 deaths of “teaching and educational professionals” aged between 20 and 64 (73 female and 66 male).

In statistical terms for educational staff, this equates to 18.4 deaths per 100,000 men and 9.8 deaths per 100,000 women.

This compares with 31.4 deaths and 16.8 deaths per 100,000 among men and women respectively in the population.

From this, the ONS states: “For both sexes, rates of death involving Covid-19 for this group [teachers] were statistically significantly lower than the rate of death involving Covid-19 among those of the same age and sex.”

In short: teachers are less at risk of dying with Covid-19 than average.

However, it is worth understanding a bit more about all the data the ONS gives us.

Definitions and data

The ONS definition of “teaching and educational professionals” covers anyone who is “qualified to teach…from primary school through to university level education”.

Yet a university seminar room and an EYFS setting are very different epidemiological environments.

Indeed, dig into the data from the ONS more and you find that 13 of the 139 deaths are higher education professionals as opposed to 23 deaths being listed as occurring among “primary and nursery education teaching professionals”.

Meanwhile, the highest setting for deaths is in secondary education, in which 52 deaths were registered - 29 men and 23 women. That’s four times higher than the deaths in higher education.

A full breakdown by all settings can be seen below:

A second look

So, the ONS tells us that 139 teaching and educational professionals have died. Yet of those, 126 - a full 90 per cent - have come from primary, secondary, further education colleges and other educational establishments.

Universities are mostly able to run entirely online; seminar rooms and lecture theatres have been empty for months. Schools are open and always have been; teachers take a risk every time they head into school, interact with parents, pupils and each other.

This is not to diminish the risks to university teaching staff; they too have faced tough circumstances and many will have been in close contact with students, colleagues and each support staff.

But the data is plain: the brunt of the Covid-19 deaths in “education” has been borne by those in schools and colleges.

True picture?

But is the total risk really lower than other professions?

Unsurprisingly, the unions have raised issues with how the data is presented. Andrew Baisley, a data analyst at the NEU, told Tes he felt it was “unhelpful” that university staff were being included alongside teachers in these calculations.

“We are talking about schools and therefore it’s almost meaningless to talk about universities in that context,” he said.

However, Paul Smith, professor of official statistics and director of Southampton Statistical Sciences Research Institute, told Tes that the ONS was simply using its Standard Occupational Classification 2010 framework and that, even if HE staff had been removed, it is unlikely it would have any sizeable impact on the rate calculated.

“The ONS has to classify profession somehow and use something that is standard and granular,” he says.

Secondary staff

However, the one group the ONS was able to break out sector-specific information for was secondary schools, where, as noted, 52 staff died from Covid-19 in the period measured.

When this rate was analysed as an overall figure free of any other education setting, the data was as follows:

- Secondary staff mortality rates are 39.2 deaths per 100,000 men (29 deaths) and 21.2 deaths per 100,000 women (23 deaths).

- This compares with 31.4 deaths per 100,000 men aged 20-64 years and 16.8 deaths per 100,000 women across the population.

Although this looks a lot higher, the ONS states that the difference was “not statistically significantly raised when compared with the rates seen in the population among those of the same age and sex”.

To understand why the figures do not change the modelling despite being higher than the national average, it’s useful to understand that the ONS generates a confidence interval (CI) for all data at both a lower limit and a higher limit, thereby creating a range between which it is confident in saying the true data point sits.

This is done to demonstrate how variations on the data, such as any teacher deaths that had occurred due to Covid-19 but were not picked up by the model, for example, have been taken into consideration in the data modelling.

When the ONS did this for secondary staff for men, the range came in between 24.3-58.6 and for women, 12.2-33.2.

Although these ranges look sizeable, Smith explains that because the range contains the overall national average - 31.4 for men and 16.8 for women - they cannot be called statistically significant.

A helpful comparison to show this in another way is to look at the CI range for nurses. The lower CI is 79.1 and the higher CI 106.1; the range is far above the national average, showing that nurses are statistically much more at risk than the average person.

Age ranges

However, as noted by Tes earlier this week, the data used to calculate the teacher risk by the ONS only covered those aged between 20-64. When you include over-65s, though, new patterns emerge:

Deaths from Covid-19 by occupation in education, both men and women aged 65 and over:

- Higher education teaching professionals: 26 deaths

- Further education teaching professionals: 34 deaths

- Secondary education teaching professionals: 96 deaths

- Primary and nursery education teaching professionals: 62 deaths

- Special needs education teaching professionals: 10 deaths

- Senior professionals of educational establishments: 25 deaths

- Education advisers and school inspectors: 6 deaths

- Teaching and other educational professionals: 20 deaths

In this age bracket, there have been a total of 279 deaths - and of those, primary and secondary schools have been hit hardest, accounting for 158 of all deaths at 57 per cent.

If we add these deaths to the deaths of tho57se aged 20-64, the overall figure jumps from 139 to 418 - and all but 39 are from those across school and college settings.

Although it seems strange that this data has been left out of the official calculations, Smith says this is due to the need to weight the statistical modelling by age as most educational staff are within the 20-64 grouping and over-65s are more at risk of Covid-19 - and there are fewer teachers above this age bracket in the profession.

Other school roles

There is another important set of data we need to examine, too - that of other teaching roles, such as teaching assistants.

The ONS data on educational staff examined so far does not include TAs, although the report does contain - in another section - data on how many of those listed as TAs have died from Covid-19.

For those aged 20-64, the ONS reports that 42 teaching assistants died owing to Covid-19: five male and 37 female. For those over 65, one man and 31 women died.

This means a total of 74 teaching assistants have sadly died owing to Covid-19 over the period reported. This takes the total up to 492.

And there is still one more set of data to consider: the ONS also lists deaths for several other key education-related occupations that are not included in its original definition or figures.

The below lists these roles and the overall number of deaths for all ages, again taken from the ONS data.

- Nursery nurses and assistants: 20

- Childminders and related occupations: 36

- Playworkers: 4

- Educational support assistants: 18

- School secretaries: 18

This is another 96 to add to the total, making 588.

Baisley says that given the seriousness of the issue with which the data will no doubt be used, it would have been better if all teaching roles were included in the key calculations.

“It’s odd they haven’t included TAs and other educational workers in their calculation. I understand it’s a standard ONS group [to leave out these roles from education data] but if they want to talk about risks to teachers, they really should have amended it,” he says.

Smith, however, says that even if this data were included, it would be very unlikely to change the rate much at all - and could potentially even send it down - because it would add a high overall number of TAs that work in schools while adding a (statistically speaking) low number of deaths to the total.

“It is unlikely that adding [teaching assistants] to the calculations would change the rate,” he adds.

Some answers, more questions

Where does this leave us?

It is clear the education profession has suffered from Covid-19 - at all ages, in all settings.

However, the ONS data does, from a purely empirical point of view, offer a sense of the overall risk of death with Covid-19 that teachers face by providing the clearest set of data yet on mortality rates.

But while the statistics may offer a guide on how safe, or not, teachers should feel in school, there is plenty that the data does not provide answers for that cannot be overlooked:

- There is no data on infection rates: many teachers have suffered from Covid, and continue to suffer, despite not dying from the disease. There is certainly evidence - as noted earlier - that infection rates in schools are much higher than elsewhere and therefore there is more risk of long-term health impacts for those working in education.

- There is also no data on when the teachers listed by the ONS died. If we knew when they died and measured it against when school were fully open and when they were in lockdown, it may show notable spikes during school’s full openings - potentially showing if the risk is higher for staff who are in school.

- We also have no data on how many staff in school administration - except school secretaries - died from Covid-19, as the ONS does not include staff in these roles in its overall education-specific data.

What we do know, though, is this sad reality: almost 600 educational professionals have died from Covid-19.

What is equally sad is that the ONS data only goes as far as 28 December. With record death rates marked throughout January, the reality is that this number is already a lot higher.

So, while Mr Johnson may insist with gusto that schools are safe, no doubt many across the education sector - at all ages and in all roles - will, understandably, still be nervous about returning.

Dan Worth is a senior editor at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters