Bickering about selection is helping nobody

The change of education secretary has predictably been met with dismay from some and enthusiasm from others. We don’t yet know what changes, if any, Damian Hinds might bring, but we can be certain that they will divide opinion. Because, let’s face it, educational opinion these days is always divided.

It is interesting that the other public sector institution facing challenges, the NHS, has - for the most part - not engaged in the petty bickering and point-scoring that has characterised the education sector.

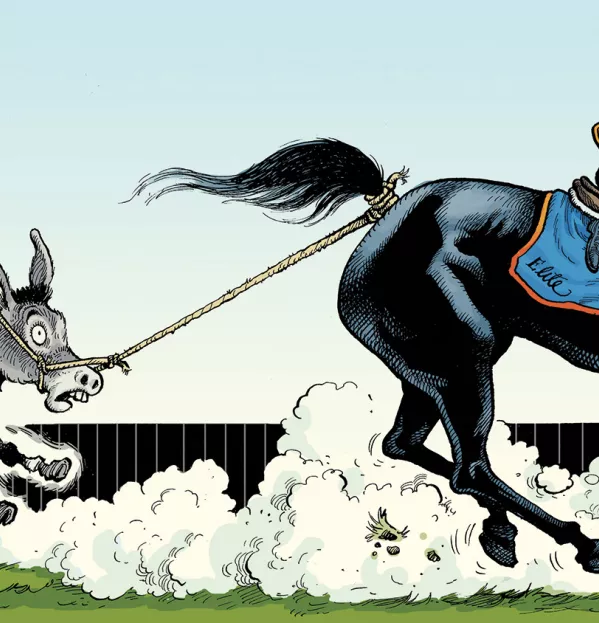

A good example of the latter is the response to a resurfaced 2014 article, written by Mr Hinds, which favoured selective schools. We can now expect a period of divisive and damaging in-fighting. The image of teachers and school leaders scrapping with the press looking on and shouting encouragement is not too far removed from the jealousies and resentments we might expect to see in the playground.

Personal agendas have often taken precedence over the wellbeing of young people. Association of School and College Leaders general secretary Geoff Barton effectively campaigned on a platform of opposition to grammar schools, forgetting that he is also supposed to be representing them.

Education has never felt more divisive and it’s our young people who are paying for it. Competition through league tables has undoubtedly fuelled this, as has the attitude of some school leaders who blame anything other than their own leadership for the failings of their school.

I have now spent more than 27 years working in education as a teacher, senior leader and headteacher, through single-sex (both boys and girls), mixed, comprehensive and grammar schools. It is as broad an experience as I could hope for. Now, as a headteacher of a successful girls’ grammar, I believe that I have something to contribute to the grammar school debate.

As far as I understand, Mr Hinds, in a chapter of a book, Access all Areas, suggested having “one unashamedly academically elite state school in each county”. I haven’t read the chapter, and until quite recently, like many others, I had no idea who Damian Hinds was. But before we start taking off our blazers and rolling up our sleeves, let’s consider what he appears to be suggesting.

A moral purpose

I have a problem with the word “elite” here. It has increasingly become an insult motivated by some form of inverted snobbery, and is too often associated with wealth and privilege. So let’s put it aside and ask: can an academically selective school, strategically placed, actually bring benefits to the young people in its area?

Obviously not everyone will get in, which is true of most successful schools, but can its existence support not only those who do, but also those who don’t? I believe it can and must.

Certainly, we have seen limited evidence to show grammars benefiting students beyond their gates, but it does happen and should happen more.

My school, Townley Grammar, has recently become the sponsor for a local secondary modern, which is currently graded “requires improvement”. By the end of the year, we will have become a multi-academy trust. We are not a large MAT and there is undoubtedly a risk to our “outstanding”-rated school. Of course, there are arguments for the financial benefits of the arrangement, but we all know these are in the long term and there are no handouts to support such an enterprise. So why are we doing this?

As educationalist Michael Fullan puts it, school leaders need to have moral purpose and they should be as concerned about the young people beyond their school gates as they are for their own students. As a grammar school head from a disadvantaged background, educated in the comprehensive system, my mission is to support able students wherever they are. By developing our practice and effectively specialising in the most able, we have a skill set and bank of experience to support schools with their able students. Let’s be honest, there are countless able young people in non-selective schools and Ofsted has recognised that they are often not served well.

There are problems to resolve and many grammar schools not only recognise this, but have been working hard to tackle them. Chief among them is social mobility. But before we run headlong into tackling this issue, we should be asking some questions: do we actually have a social mobility problem? What do we mean by this anyway? It has become educational orthodoxy to uncritically repeat “social mobility” as an educational goal and without any agreed definition; is it economic, social, intergenerational or intragenerational? And are we using the same definition each time we discuss it? (A useful read is Peter Saunders’ 2010 book, Social Mobility Myths.) Furthermore, it may well be a worthy social aim, but is it the role of education? If so, how much of a focus should it receive compared with other educational ambitions?

Working together

Regardless, we certainly need grammars to have a more diverse socioeconomic and ethnic population. My school has about 3.2 per cent on free school meals and over 7 per cent as Ever 6 FSM. It’s a higher rate than many, but I recognise it’s not enough.

We have included FSM in our admissions criteria, but that doesn’t help if the student doesn’t pass our test. We don’t use rank-order selection, which in many cases can favour more affluent families, and we were among the first to adopt the selection test from the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, which is more coaching-resistant.

Yet it is really our work with primaries that will help. Those primaries that will work with us get a range of outreach activities, such as a science roadshow, and we have begun offering maths and English tuition to FSM students in selected primaries. We would like to do more and are actively developing our relationship with primary trusts to better achieve this.

So let’s start with a unified approach to education. comprehensives, secondary moderns, grammars, free schools, secondary and primary, all coordinated together.

How would this work? It means working in regional hubs, strategically placed according to local populations and need. It means designing an all-through curriculum that joins up at key transition points. It means having grammars specialising in teaching the most able, but also supporting able students in neighbouring schools. It allows for school specialisation, eg, technical, but also mutual support rather than competition. It means not letting market forces dictate educational provision and, yes, it means that grammars have a place, too, but a responsibility to collaborate, including on admissions.

Let’s regulate tuition companies and let’s have something like a common admissions test, with oversubscription based on distance and disadvantage, not test scores. And yes, let’s have an admissions process that supports disadvantaged students, potentially with a percentage of reserved places. Let’s go even further and fund places to be kept open for transfer at Year 9.

If we really want to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds, let’s start at primary, with secondaries linked to specific primaries to support those students, but let’s fund that.

Pupil premium is useful, but it’s tied to a specific school whereas it could be used to support transition. And can we have some meaningful accountability for pupil premium? If you are not successful in closing the gap, then perhaps funding should be transferred to another school, with the requirement of sharing its practice.

This calls for a change of mindset. Our whole education system seems overly focused on applying funding to areas or issues that are already failing rather than investing in the successes and sharing them. More money doesn’t create better leadership; in fact, at times it can seem like giving money to a gambling addict in an attempt to cure them. You simply cannot buy your way out of every problem.

Most importantly, though, for all of us in education, let’s stop bickering with each other and remember our common purpose.

Desmond Deehan is headteacher at Townley Grammar School in London

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters