‘The biggest period of uncertainty in decades’

Schools are facing huge change and volatility this summer, thanks to the biggest shake-up of the exams system in three decades.

Next week, pupils will receive exam results for the first set of new “linear” A levels - involving less coursework and a move away from modular exams - and later this month, schools will find out how their pupils performed in the tougher GCSEs.

Despite attempts by Ofqual to reassure schools that pupils will not be adversely affected by the sweeping exam reforms, a vast amount of uncertainty remains.

Stuart McLaughlin, headteacher of Bower Park Academy in Romford, East London, who has been working in schools for 30 years, says: “This is the biggest period of uncertainty. The fact that they have changed the exams and the grading system has made it the most difficult period for a long, long time.”

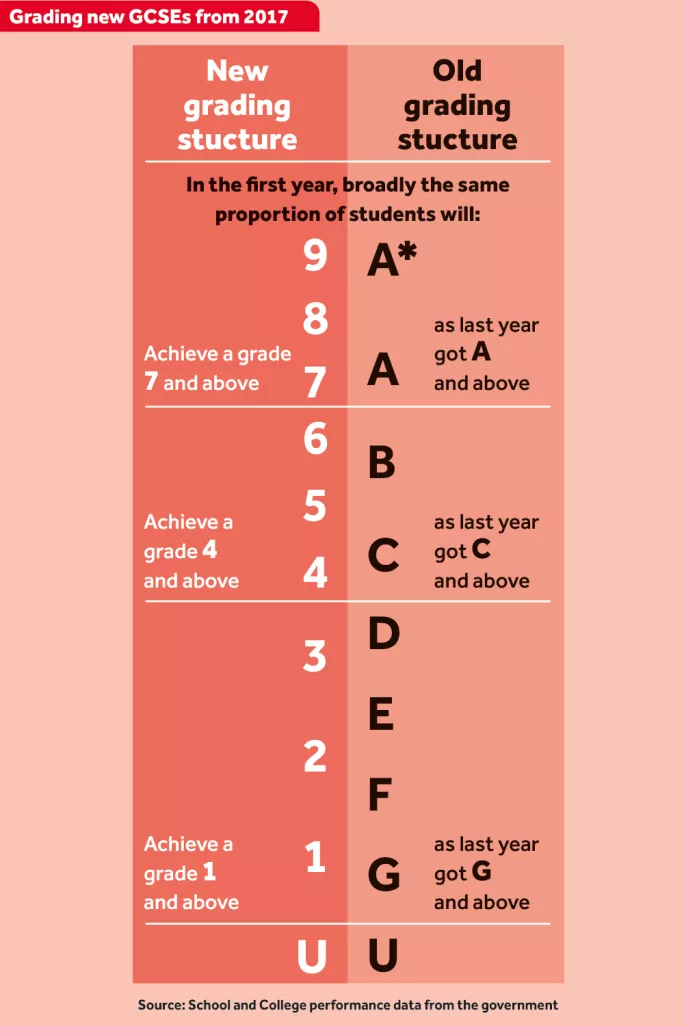

One of the biggest concerns is that two GCSE grading systems will now run alongside each other for three years. As the reforms are phased in, pupils will receive a mix of letters and numbers. Pupils will be awarded numerical grades (from 9 to 1) in the new English literature, English language and maths GCSEs this summer, but they will still receive A* to G in other subjects.

The nine-number scale does not directly compare with the eight-letter scale. “[Teachers] probably have no idea whether a pupil has any chance of getting a grade 9 or not,” Barnaby Lenon, chair of the Independent Schools Council, says. The government’s decision to have two different pass grades - 4 as a “standard pass” (the minimum level required for English and maths) and 5 as a “strong pass” - has further confused matters.

Because of the changes, on GCSE results day it will be difficult for schools to compare year-on-year performance, and the way that the results are reported will differ from school to school. In fact, a group of heads in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, have taken the decision not to publish their results this year.

‘It is not comparable’

Malcolm Trobe, deputy general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, anticipates that more schools will take a similar decision because of the “very messy” grading system.

“It is not comparable and you have a mixed system, which is going to make it really, really difficult to understand,” he says. “And the same will be true in 2018 and 2019.”

Adding to many headteachers’ anxiety, state schools will have to wait until the autumn to find out their Progress 8 scores. Sally Collier, chief regulator of Ofqual, has warned Ofsted, regional schools commissioners and governors against making “knee-jerk” reactions to results this year.

Sarah Hannafin, policy adviser at the NAHT headteachers’ union, says: “It is unwise to draw conclusions about a school’s success or failure from the data this year. We need to be very careful about any heavy-handed intervention on the basis of this year’s results, as it is inappropriate.”

Schools that relied heavily on coursework marks could find their results drop in the 13 new linear A levels and three new GCSEs being awarded this year (see timeline, above).

However, despite all the reforms, Ofqual insists that national results will be similar to last year if the cohort is similar to last year.

But where the cohort changes significantly, results could alter. The number of GCSE English entries jumped by around 50 per cent this year, after some schools moved away from IGCSEs as they no longer count in the performance tables. More pupils are doing English literature now that it counts towards Progress 8. This means that more lower-ability pupils are being entered for the exams, which could lead to a fall in the overall proportion of top grades this summer.

Chris Keates, general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union, says: “The changes to A levels and GCSEs have undoubtedly created great uncertainty and may well lead to greater volatility in this year’s results.”

Keates accuses the Department for Education of failing to prepare schools adequately for the upheaval. However, a DfE spokesperson responds: “This year’s GCSEs and A levels are the next step in a six-year process of reform to ensure young people have the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in the future.

“Teachers, schools and universities were consulted throughout their development and, working with Ofqual, we have published multiple resources over a number of years about the new qualifications, including information packs for every school and a dedicated website to answer questions people might have. We have also deliberately phased in the introduction of the new GCSEs to reduce workload on the profession and ensure teachers and students have time to prepare.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters