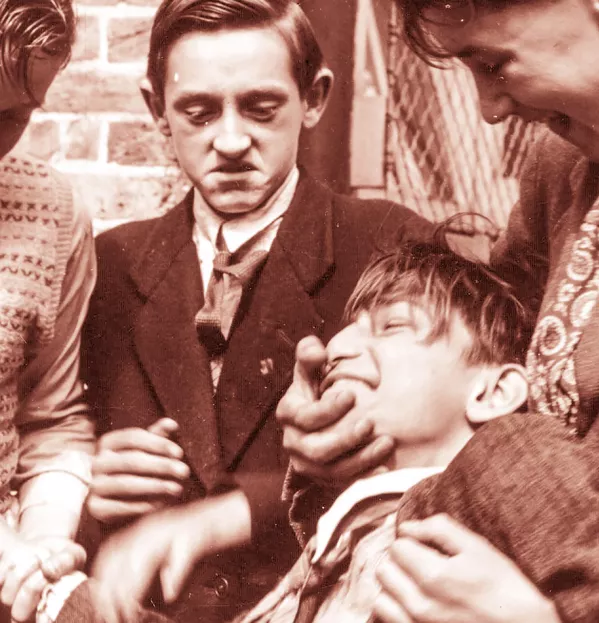

Bullying: we need to listen to pupils’ school experience

We have been asking prominent figures in Scottish education about their own schooldays for almost a year now. The “10 questions with …” slot got under way in this magazine in January, with Pauline Stephen, chief executive of the General Teaching Council for Scotland, being the first Scottish educationalist featured in the series.

Every fortnight since, we’ve been asking someone in Scottish education to reflect on their career, what inspired them to enter teaching, and what we need to change about the system - as well as the best and worst aspects of their own time in school.

Very often, the worst aspect of their own time in school was bullying - either bullying from other pupils or from school staff.

The people we feature tend to have last donned a school uniform decades ago. But as Anti-Bullying Week 2021 draws to a close, it is worth reflecting on how the current generation working their way through Scottish schools might answer that question in the future: what will have been the best and worst things about their time at school? One wonders if bullying will still feature prominently in their responses.

Pauline Walker, headteacher of Edinburgh’s Royal High School and chair of the BOCSH group of heads, took part in the Q&A in February. She spoke about moving house and starting her second year of secondary at a new school. There was bullying and, she said, “I was alone and I found it really hard.” Now, every time a child joins her school she goes out of her way “to make sure they are OK and they have got a friend”.

Eileen Prior, executive director of Scottish parents’ organisation Connect, whom we featured in May, remembered the “punitive, authoritarian approach” that was taken to discipline when she was in school - belting was still permitted and there was “shouting” and the “throwing [of] blackboard dusters”. And “all of that kind of stuff I found really intimidating and bullying”.

Mark Priestley, the University of Stirling professor of education whose interview was published in June, talked about “the culture of casual violence” among pupils that existed where he was in England and teachers who “turned a blind eye to it [while] some were actually bullies themselves”.

Undoubtedly, times have changed - the belt was removed from schools long before the current generation entered a school building.

Focus on kindness

Respectme, Scotland’s national anti-bullying organisation, has been trying to put the focus on kindness this week because, as director Katie Ferguson put it in an online article for Tes Scotland this week, “culture - more than anything - determines whether bullying thrives … or is prevented from taking hold”.

Certainly, a lot of Scottish schools now have this focus on kindness.

The adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) movement has attempted to encourage schools and teachers to see behaviour as a form of communication and to “get curious” about why some children behave the way that they do, instead of punishing them for it. There has also long been a focus in Scottish schools on the concept of nurture.

However, it would be naive to pretend everything is perfect. Prior pointed out that, while the belt is no longer in use, there can still be concerns about what goes on “behind closed doors”.

She highlighted the use of restraint and isolation as issues that need to be dealt with today. Research carried out by the children’s commissioner’s office in 2018 found that it was impossible to know “with any degree of certainty” how many incidents of restraint and seclusion were taking place in Scottish schools each year, or which children were most affected - or how often or how seriously - because councils were failing to record the data.

So, what exactly do we know about how happy Scottish pupils are and the extent to which they experience bullying?

The Scottish government records figures on child wellbeing and children’s attitudes to school via its National Improvement Framework, which is designed to monitor the performance of the education system.

However, many of the figures on these themes date back to 2018 because they are taken from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey, which is only run every four years. Schools and councils will undertake their own work on this but inevitably it will be patchy.

At a meeting of the Scottish Parliament’s Education, Children and Young People Committee last week, Professor Gordon Stobart gave evidence on his recent report for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development on the future of qualifications in Scotland. He said that Norway carries out an annual survey of students in which they comment on their school experience and, by comparison, was “surprised by how little systematic research on pupil perceptions and attitudes is being done in Scotland”.

Reading the reflections of adults on their schooldays is interesting - you find out about their early experiences and how they shaped them.

But surely we should also be asking the young people in the system today what they think of it, as they experience it? The advantage, of course, is that then you can build on the best aspects - and do something about the worst.

But if you don’t ask the questions and gather data, the danger is that you don’t address problems - and that many years later, just as one of our interviewees recalled with clear regret, the current generation is left with “very poor memories” of their schooldays.

Emma Seith is a reporter at Tes Scotland. She tweets @Emma_Seith

This article originally appeared in the 19 November 2021 issue under the headline “The times have changed - but has the school experience?”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article