‘Can anybody out there hear us?’

It’s not as if they haven’t tried. The unions, heads and governors, that is. They’ve made the right noises: asking parents for handouts, warning of chronic staff shortages, threatening strikes and even predicting a four-day week.

But the public - and the editors in charge of national newspapers and radio and television news running orders - don’t seem to get it. Schools in financial crisis…it’s an education story, right? Or a local story? Page 5, 10, 20? The very occasional front page seems to be given in sympathy, or necessity. “Chuck the ‘schools with no money’ story in.”

And the public skims past: “It all looks OK in my child’s school, after all.”

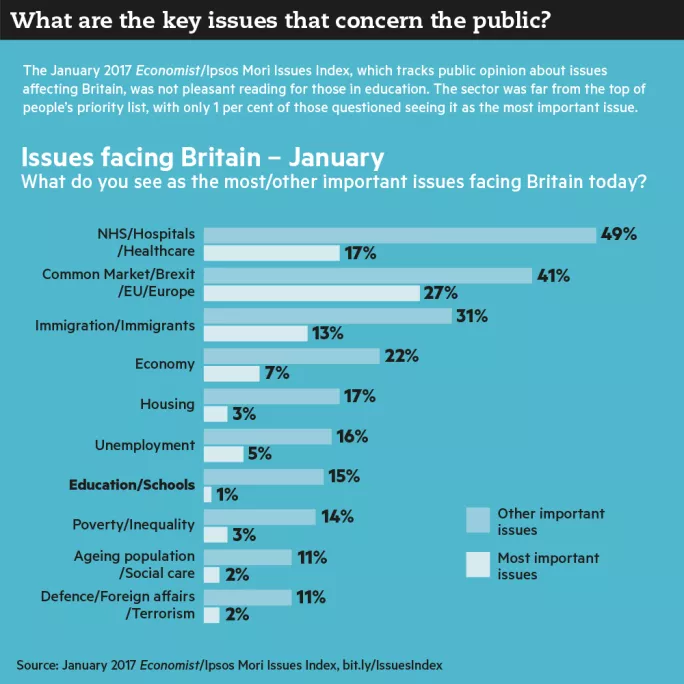

The NHS, now there’s a story. At the mere whiff of less-than-adequate service in a hospital caused by a lack of funding, the coverage is front, centre and hyperbolic. The public rises and vents, and the government scrambles: “We’re outraged. This must change.”

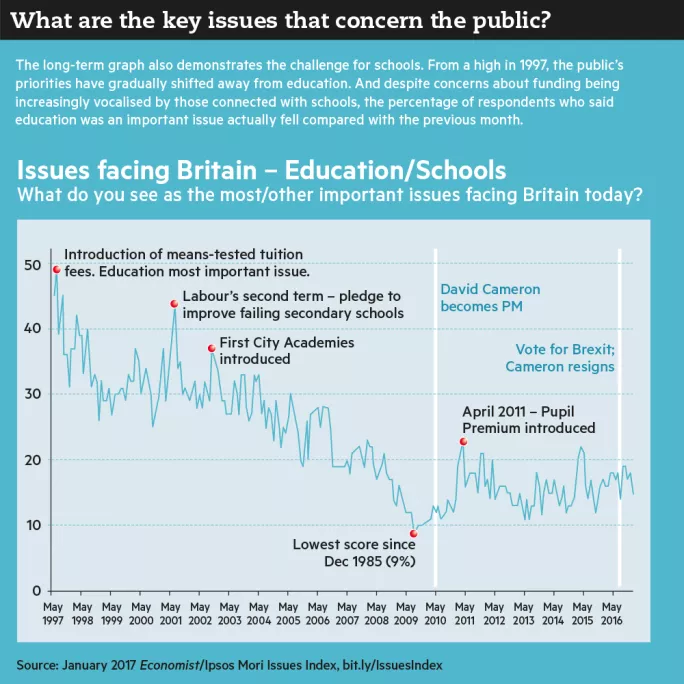

As the school funding crisis bites harder - the bruises becoming more visible in the form of rundown buildings, larger class sizes, lack of staff - those who work in education need to ruminate on why their message is not penetrating the public consciousness as deeply as many argue it should. Why the NHS and not schools?

For, without public pressure, the chances of the government making the changes heads claim are absolutely necessary for the viability of educating the next generation are very slim indeed.

Mounting costs

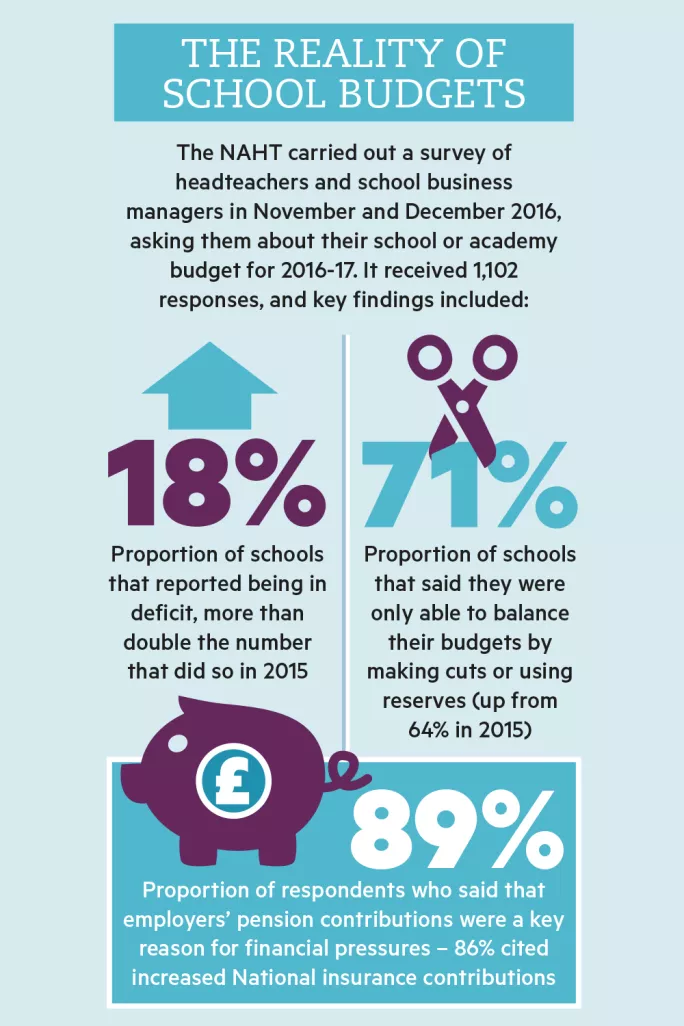

That schools are struggling financially is clear. In December, the National Audit Office (NAO) warned that schools were facing real-terms cuts and would have to make savings of 8 per cent by 2019-20. The public spending watchdog added that schools had “not seen this level of reduction in spending power since the mid 1990s”.

The key issue, it said, was per-pupil funding not rising with inflation at the same time as £3 billion was required to fund pay rises, the introduction of the national living wage, higher national insurance and pension contributions and the apprenticeship levy.

In the same month, the government unveiled details of the new national funding formula, which showed that, although 10,740 schools would gain, 9,128 would lose out. The unions claim that, when taking into account other funding pressures, 98 per cent of schools will suffer real-term cuts under the formula.

“I think a lot of schools were thinking that when the national funding formula arrived they would be much better off, but they’ve now realised that they’re not going to be and some of those schools that are already poorly funded are actually going to be worse off,” explains Usman Gbajabiamila, policy adviser on pay, conditions, pensions and school funding at the ATL teaching union.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies revealed in February that per-pupil spending is set to fall by 6.5 per cent between 2015-16 and 2019-20 - the biggest fall in 30 years. And an open letter from the NAHT headteachers’ union and the National Governors’ Association in the same month added that the cuts to the Education Service Grant was also having a significant impact. The convergence of all of these issues - and more - at roughly the same time appears to have created a tipping point for many schools, according to Valentine Mulholland, head of policy at the NAHT.

“We do believe school funding is in crisis,” Mulholland says. “Wherever we go in all our regions and branches, it’s the number one issue for our members.”

This was highlighted in the association’s recently published Breaking Point report, which found that the number of schools in deficit had increased by 10 percentage points - from 8 per cent to 18 per cent - since the 2015 survey. The 2017 report, which polled more than 1,000 headteachers and school business managers in England, also found that the number of schools that were able to balance their budgets only by making cuts or using reserves had increased from 64 per cent in 2015 to 71 per cent in 2016.

Public sector cuts are, of course, a regular issue. Schools have been here before, numerous times. But most heads claim it has never been quite this bad.

“The General Annual Grant money is the same, but real costs have risen and local authority-based funding has been reduced - Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index [IDACI] and SEND [special educational needs and disabilities] funding in particular,” says Keziah Featherstone, headteacher of the Bridge Learning Campus in Bristol. “Meanwhile, universal free school meals means fewer key stage 1-2 parents have registered for free school meals, which affects additional funding.”

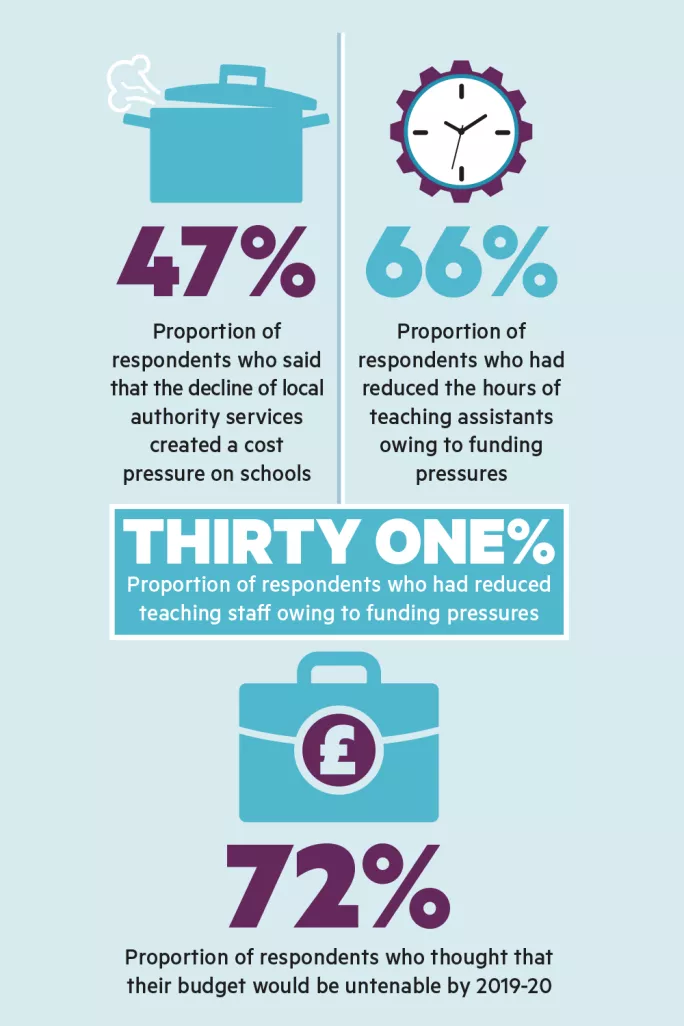

Up to last year, most schools had coped with the financial pressures by picking off “the low-hanging fruit,” says James Bowen, former headteacher and now director of middle leaders’ union NAHT Edge. “So maybe they haven’t upgraded computers and [they’ve] put decorating classrooms on the backburner,” he adds.

But in the past 12 months, the big calls have had to be made. “You can cut away the things that are not absolute must-haves, but what heads are saying to us is, ‘We’ve done that, but now we’re getting to the pinch point where we are talking about human beings and staff - we can’t cut any more at the edges’,” Bowen explains.

Individual schools have reached that point at different times across the past 12 months. Back in March last year, TES ran an anonymous cover feature from a head who laid his school’s finances bare and made it clear that he was struggling to keep the institution afloat (“How my school is losing the battle with funding cuts”, 11 March 2016).

In an effort to force the issue into the spotlight again as the funding situation grew even worse, John Tomsett, headteacher at Huntington School in York, revealed himself to be the author at the start of this year.

In his article, he details not just the hammering his school building has taken owing to lack of funding (dodgy fire alarms in need of replacement but no money to do it, faulty electrical systems and heating) but also the impact on education (fewer teachers, fewer resources, redundancies, larger class sizes and reduced educational opportunities).

Since then, other heads have revealed their own stories - posts left unfilled, reduced teams, larger class sizes, crumbling buildings, inability to provide for every child (particularly those with SEND). TES has run numerous articles from school leaders and unions warning of impending catastrophe should school finance problems not be addressed.

And yet, despite the dire figures, the horror stories, the pleas of unions, headteachers, and governors, for the most part, the school funding crisis has remained a niche story. An education story. The public outrage and corresponding media explosion that the underfunding of the NHS attracts has not happened. Why?

A big part of the problem is visibility. The NHS has waiting times, beds in corridors and people desperately in need of treatment sitting in ambulances because of a lack of A&E beds. The problems are clear, the case studies harrowing and relatable, the imagery immediately accessible. It’s an easy tale to tell. In schools, the story is more complex and the physical signs of trouble are harder to see (a fact acknowledged in the recently launched #whatwouldyoucut campaign from ASCL, which aims to make the cuts visible).

Death by a thousand cuts

“If I were to, say, cut all departmental budgets by 30 per cent, it is unlikely that many parents, or children for that matter, would see the difference,” argues Jarlath O’Brien, headteacher at Carwarden House Community School, a special school in Surrey. “Equipment might degrade over time and not be replaced, causing some issues with, say, access to laptops. Science practicals may be between four [pupils] instead of two, and so on. This causes minor issues that don’t amount to anything obvious to parents, but they do affect the quality of education on offer.

“Similarly, stop funding tea and coffee for staff. I may change our sickness policy. I may not use supply staff and rely on higher-level teaching assistants or cover supervisors. All of these are invisible, even to many within the school, but they add up over time.”

The “invisibility” of the issue can in part be explained by the incredible work of headteachers and schools. They have shouldered the burden of education cuts themselves, finding often ingenious ways to make ends meet, because they are desperate to safeguard students and their learning.

This has a two-fold impact, according to Helena Marsh, principal of Linton Village College and executive principal of Chilford Hundred Education Trust: the problems are “hidden” from parents; and heads are too busy trying to make the figures work to speak out about funding and campaign for changes. There have been no junior doctor-style marches by headteachers, and those that do speak out tend to be in the minority, not the majority.

‘No one is listening to us “whingeing teachers” and they only will when we have no teachers in front of classes’

“Most school leaders have, understandably, prioritised their energies on making their own budgets balance, often dealing with reduced staffing and increased workload in order to do so,” she explains. “They haven’t necessarily had the time, energy or inclination to vocalise their funding concerns and challenges.”

They might also have reservations about going public with their concerns for fear of their words falling on deaf ears, according to Geoff Barton, headteacher at King Edward VI School in Bury St Edmunds and general secretary-elect of Association of School and College Leaders.

That’s a real possibility, says recently retired primary school headteacher Colin Harris. There is a perception problem of teachers in general of “crying wolf” that is stopping the messages being related about funding from getting through, he argues.

“No one is really listening to us ‘whingeing teachers’ and they only will when we have no teachers in front of the class,” Harris says. “The media have standard views on education and it is almost impossible to change their stance. The reality is we have a system now running on empty and the result will be a decrease in results and an increase in teacher leavers.”

Rather than visibility, could it be that in the commotion of multiple campaigns - against Sats, Progress 8 and English Baccalaureate, too many exams or too few (depending on your viewpoint), performance-related pay, etc - the funding message is getting lost? Worse, is it being tagged as part of general, as Harris puts it, “whingeing” from teachers?

“Colin has a point,” Marsh says. “Teachers only tend to make front-page news when on strike action or criticising government initiatives. They can be seen to be whingeing and negative so the campaign for sufficient funding for education may have become lost.”

Featherstone adds: “I agree that a lot of the public will see teachers as whingeing and militant for the sake of it. I hear a lot that teachers get it easy, and a lot of people carry baggage from their own time at school, too.”

It is not just teachers who are failing to get the message across, though. A limited number of parent groups are now campaigning on the issue and they are struggling to get traction as well.

Fizz Bewley, coordinator of Fair Pupil Funding, a lobby group spearheaded and backed financially by parents across the UK, says the issue is that many parents are not aware - or not interested - in general concerns around education funding.

“You’ve got those who fully understand the complexities of the issues and often they have some sort of links to education,” she explains. “You’ve also got those who fall into the vast majority who simply accept what their school tells them. And if the school goes quiet on something, they go quiet. Then you do get a batch of parents who say their school is doing fine and they don’t see that there is an issue.”

Getting through to those latter two groups of parents is tough, it seems, for all those trying to raise awareness of the crisis. If that connection could be made, it would be a major step in getting more coverage.

But some argue that those people will never be reached unless all the different parties - parents, heads, governors and unions - pull together. The main problem with the funding message not getting through, the theory goes, is that there are too many smaller, competing messages rather than one big one.

“I think if heads and boards of governors got together and did the sort of work that they’re doing in West Sussex, it would make a huge difference, because they are not the only county in this position but they have organised themselves,” says Emma Knights, chief executive of the National Governors’ Association. “Their campaign is a great example of how you go about making an issue visible.”

Knights also believes that governors should start lobbying their local MP to raise awareness of the problems they are facing.

However, concerns raised by Conservative backbenchers in constituencies set to lose out in the new funding formula have, thus far, not prompted much ministerial movement.

The ATL’s Gbajabiamila concurs with Knights that interested parties across the education sector need to collectively start putting pressure on the government.

It’s an all-in approach, based on the idea that if every school in the country were shouting the same message, the general public could not help but hear it. But that would require a level of collaboration across multiple groups that has rarely, if ever, been managed.

It would be problematic enough just to get all the heads on board, says the NAHT’s Bowen: “As a head you don’t want to admit ‘I’m struggling financially’ because we’re in a competitive market and a parent might say, ‘If that school is struggling financially, I will go to the one further down the road’.”

This obstacle is one that Gbajabiamila has already encountered through his work on the School Cuts campaign - a cross-union initiative that highlights funding cuts for individual schools.

“One of our members called me up and said, ‘Why have you done this?’ and we said, ‘We’re trying to highlight that schools are badly funded’. He said, ‘My school is on there [the School Cuts website] and now anyone in my area can go on your site and see that my school is struggling financially and I don’t want that to happen’.

“I explained that he had to think of the bigger picture here and, if we don’t say something, schools like his will continue to struggle.”

Crisis - what crisis?

There’s another problem on the heads front that may make uncomfortable reading but could be one of the major issues with getting public support for schools’ attempts to secure more money: some schools, it could be argued, aren’t actually in a funding crisis.

Certain institutions - particularly in London - are doing OK financially. And a headteacher from a large school in the North of England says funding isn’t an issue for them. They believe that many heads are saying there’s a “crisis” when actually they are hoarding money for the future.

“My view is that you should spend the money you have on the children who are in the school,” the head says. “The problem is a lot of people start saving for rainy days and what makes my blood boil is the amount of money sitting in school reserves. I know that in some schools it is a small fortune.”

Former Ofsted HCMI Sir Michael Wilshaw certainly seems to think that the funding crisis is being over-egged. He told BBC Radio 4 last month that schools had enjoyed 20 years of “largesse” and, in some cases, heads were awarding themselves large salaries. He urged heads to adjust to the new financial landscape.

And Jonathan Simons, former head of education at the Policy Exchange thinktank and now director of policy and advocacy at the Varkey Foundation, adds that the “crisis” narrative simply doesn’t fit with reality when you consider other public services cuts.

The failure of the message he argues, is down to the fact that education finances are simply in less peril than other public services. He accepts that many schools are going through tough times at the moment due to funding constraints, but he adds that this comes off the back of an incredible period of funding growth in the sector.

“If you look at the financial position for schools, then even in the past five years, compared to other public services, they have done so much better,” Simons says.

As a result, it does not really matter how loudly the sector shouts, the government and the media have their sights set on where the financial situation is more acute, he argues.

“If schools want more money, they have to make a case as to why they need it above any other public service, but if you look at the NHS and social care stuff that’s in the news, schools are nowhere near that,” Simons says.

‘You don’t want to admit “I’m struggling financially” because we’re in a competitive market’

Could it be that rather than a failure of the message, the issue with wider awareness of schools’ financial woes is actually down to the message being flawed? That the crisis is not actually a crisis?

The unions and those working in schools will tell you there is a word missing from Simons’ analysis: “yet”. Some schools are already in dire circumstances, but many are trying to raise awareness now so they don’t fall into that situation. Other public services may be struggling more, but does that mean the solution is simply to let education join them?

“I think this is the year that we are going to reach breaking point,” Bowen says. “Heads have been telling us for a few years that by the time we reach 2017-18, their budgets will no longer be viable and they’re not going to be able to make them work. And we’re at that point now.”

In all likelihood, many schools will go beyond that into a situation where children’s education is being further damaged by a lack of funds. Despite increased coverage of school funding in the past few weeks, ultimately, the failure to get public buy-in to the crisis in the same way as the NHS has managed has led us here.

In this week’s budget, there was more money for free schools and a negligible sum for school buildings, but no promises to fix funding. The government isn’t listening because they don’t think the public is, either.

And now schools face a further worry: if their voice continues to be ignored even in the desperate times to come, what then?

Simon Creasey is a freelance journalist based in Kent @simoncreasey2

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters