The casualties of Whitehall’s long turf war over inspection

Your school’s recent Ofsted inspection may have been tough, but the leadership team has dusted itself off, rallied the staff and set off on the long journey to improvement.

Then the other “inspector” arrives.

Although Ofsted is the public face of school inspection, there is another organisation that visits schools, writes reports on their performance and tells them what to do to improve.

However, unlike Ofsted, the Department for Education’s regional schools commissioners (RSCs) system operates largely in private, and can directly decide whether a school stays open and whether its leaders stay in their jobs.

For schools already weighed down by funding pressures, teacher shortages and high-stakes accountability measures, this “shadow inspection regime” can be more than just another burden. It can mean that instead of getting on with the job of improving education for their pupils, schools are pulled in different directions by a power struggle between two rival organisations.

“In a number of cases, members have said to us that contradictory advice has become a significant barrier to the school improvement journey they are on,” says Rob Kelsall, a senior regional officer at the NAHT heads’ union.

How could schools ever have been placed in such a situation?

It will almost certainly further infuriate those schools caught in the crossfire to hear that the origins of their pain are personality clashes at the top of the schools system, Westminster power plays and a resulting Whitehall turf war between Department for Education schools commissioners and Ofsted.

This is a story of the ad-hoc way in which the academy system has been stitched together - unplanned and not fully thought through - allowing empires to be quickly constructed and then demolished again.

It is also the story of two knights of the realm: how one, Sir Michael Wilshaw, fell from grace as Michael Gove’s “hero”, and how another, Sir David Carter - the DfE’s national schools commissioner - was built up as a rival centre of power. For civil servants watching the battle unfold, it was “King David versus King Michael”.

To read the DfE’s website, the separation between Ofsted and the RSCs seems clear. “Ofsted is responsible for inspecting and reporting on the quality of education that schools provide,” it says. “RSCs decide whether intervention is necessary based on Ofsted’s inspection results and accountability measures for school performance.”

Key responsibilities

But, in practice, the division of responsibilities has been much more blurred - something that stems from the fact that both organisations have a hand in monitoring schools and holding them to account.

One of the key responsibilities of the DfE’s eight RSCs is to decide whether schools in their region are performing well enough, and what should happen to those that are not. And from the start, they have sent education advisers to visit schools to help inform their decisions and report back on the progress being made. It is these visits, and the letters the RSCs write to schools afterwards, that many complain are simply inspections by another name.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), says that the steady expansion of the commissioners’ role has led to more monitoring than heads can cope with.

“We are just over-monitored and probably under-led because leaders’ heads are spinning wondering where the next inspection is coming from,” he says.

Kelsall cites one school in the East Midlands that received advice from Ofsted about what to do after being judged “requires improvement”, which was then “completely contradicted” by the offices of the RSC.

“That led to many months of tension, anxiety and confusion,” he says.

“Rather than that school going forward on that improvement journey, it got in that cycle where the focus came on who was calling the shots, and, ultimately, the improvement got lost and the end result was not a very satisfactory one.”

The roots of this mess go all the way back to a fraught period when Wilshaw was Ofsted’s chief inspector and Gove was education secretary.

It had taken Gove months to persuade Wilshaw - previously lauded as the headteacher of Mossbourne Community Academy in Hackney, East London - to take over at the inspectorate.

But having got his man, it didn’t take many more months for the relationship to start to sour. Gove’s advisers soon became concerned that while Wilshaw had an impressive record as a successful, traditionalist academy leader, he was failing to make the reforms they felt were necessary at Ofsted.

By 2014, Gove had succeeded in securing the exit of Labour peer Sally Morgan as Ofsted’s chair, despite Wilshaw’s pleas. The chief inspector declared he was “spitting blood” over suspicions that the education secretary’s special advisers were briefing against him.

Meanwhile, Wilshaw was engaged in a long-running tussle with the DfE over his wish, ultimately unfulfilled, for Ofsted to be allowed to inspect multi-academy trusts. The Ofsted chief, as far as some in the DfE were concerned, had become a problem.

By late 2015, Gove was long gone from education. But Wilshaw was continuing to use the megaphone his position afforded him to voice ever louder concerns about the government’s flagship academies programme.

No matter how frustrated ministers became, they could not silence him. But the DfE had a plan. It had a second knight waiting in the wings who it would set up as a rival.

Enter Sir David Carter, another decorated ex-academy head who had also been considered as a potential Ofsted chief. But there were hopes within the DfE that appointing Carter to another role would give him an even bigger voice as the new power in the rapidly evolving schools system.

Carter’s appointment as national schools commissioner, boss of the eight RSCs, was announced in December 2015. The DfE believed it had found a heavyweight who would be able to push back against Wilshaw. And in his first set-piece interview, Carter duly outlined to Tes his belief that the “all-encompassing role of the RSC is a more significant one than the HMI [Ofsted inspector]”.

‘Faceless’ RSCs

But Wilshaw gave as good as he got. Weeks later, he told the Commons Education Select Committee that RSCs were “faceless”, and criticised them for not doing enough with underperforming academies.

No wonder this group of MPs said that at times “the relationship between the national and regional schools commissioners and Ofsted appeared to be strained”. But that was effectively what some within the DfE had wanted - “King David” had been set up to cut “King Michael” down to size.

The fact that the new monarch then gradually started to encroach on the territory of the old, creating a dual accountability pressure for schools, is hardly surprising.

Since 2014, the RSCs’ responsibilities have grown in a way that the unplanned nature of the new academies system made almost unavoidable. As one Westminster insider says, “their role is unclear, and the way it has been interpreted has led, as inevitably would happen in any bureaucracy, to rapid expansion”.

In 2016, RSCs were given new powers to convert all “inadequate” schools to academy status, and decide the fate of all “coasting schools”. These new legal powers greatly expanded the number of schools that the RSCs have responsibilities for, and so greatly increased the number on the receiving end of visits from school advisers that were seen as duplicating the work of Ofsted’s inspectors.

Significantly, the DfE designated “coasting” as a new category of schools, defined purely on the basis of data, with RSCs given the job of judging whether a school was performing well enough, whether it needed extra help, and what its future should be. Ofsted was out of the loop.

Last year, MPs noted that these changes had “brought the remit of the RSCs and Ofsted closer”. For schools, that meant more duplication, confusion and pressure.

Financial fortunes

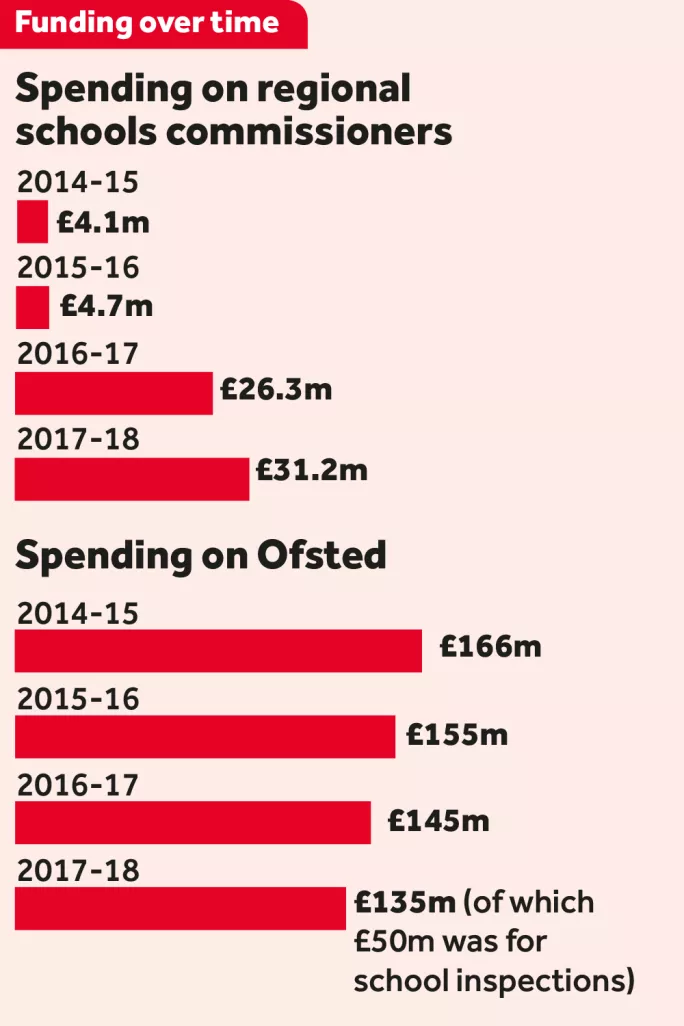

The importance that the DfE has placed on the respective organisations can be judged by their varying financial fortunes. The RSC empire has grown dramatically. Originally costing £4.7 million, that figure has risen to an estimated (by the DfE) £31.2 million in 2017-18 - partly through existing staff being moved into RSC teams and partly through recruits for extra posts.

Kelsall describes this “steady but very vivid growth” as “bewildering” for headteachers, especially with schools under increasing financial pressure. Tes has also learned that there are concerns in Ofsted that some advisers used by the RSCs were the very same people cast off by the watchdog as not being up to the job of inspecting schools.

By contrast, Ofsted is seeing its funding cut by 38 per cent between 2010-11 and 2019-20. But that does not mean it has lost the war.

Some might have expected the new Ofsted chief inspector, Amanda Spielman - who was perceived as less combative than Wilshaw - to cool temperatures and end the conflict. But her arrival, and the cuts, have not led to Ofsted surrendering territory to the RSCs. If anything, the reverse may be true.

Launching its corporate strategy last September, the inspectorate decided to refight Wilshaw’s 2014 old battle, again demanding new legal powers to inspect multi-academy trusts.

And when it comes to the overlap between its work and that of the RSCs, Ofsted is standing firm. A spokesperson says its role is “clear and well-established in statute and regulations”, adding: “We inspect and report, while RSCs take the lead after that, including intervening where schools are underperforming.”

As for the role of the RSCs, it is “a matter for the Department for Education”.

Addressing the overlap

So does that mean that these overlapping school inspections will continue, regardless of the cost and the extra burden it places on schools? The welcome news from the DfE is that the answer finally appears to be “no”.

With Wilshaw out of the picture, much of the rationale for creating an alternative power base has gone. And in the stand-off between two giants of England’s schools landscape, it seems the DfE has blinked first.

In December, it raised the overlap, and its impact on schools, as something to be addressed in its flagship plan to improve social mobility, Unlocking Talent, Fulfilling Potential.

Then dramatically, only last week, Carter revealed that he was ceding ground to Ofsted, ending the vast majority of the visits to schools by RSC advisers (see bit.ly/RSCreduce).

Acknowledging the negative effect on schools, he said: “There is no point in having two bodies both working at school level. The downward pressure that places on the system is, I think, part of the workload challenge.”

He said his plan was that RSCs should now work at the level of the multi-academy trust.

It seems that more than three and a half years since RSCs first started occupying Ofsted’s territory, they are beating a retreat.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters