Could hybrid schools offer middle ground on selection?

The prospect of a new generation of academic selection has put England’s 163 grammars back in the spotlight.

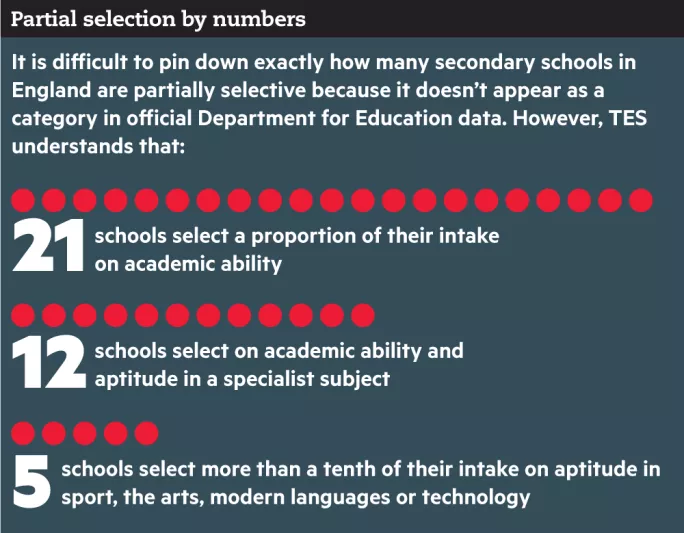

But significantly less attention has been paid to the more than three dozen partially selective secondary schools.

But this little-known and little-understood sector of English education - occupying a middle ground between grammar schools and comprehensives - could also be about to receive a boost.

Theresa May plans to end the ban on expanding selection by ability, and this will include allowing more partially selective schools - in the words of the government’s Green Paper, schools that “take a proportion of their places by ability or aptitude and a proportion without reference to aptitude or ability”.

The prime minister’s proposals could trigger a new wave of hybrid schools, and headteachers of existing schools increasing the proportion of pupils they select.

So what would teaching in them be like? How different are partially selective schools, and why have they continued to operate a “third way” on admissions?

Ashlawn School, in Rugby, Warwickshire, selects 22 per cent of its intake - 10 per cent on a modern foreign languages aptitude test and 12 per cent on more general academic ability.

Aspirational students

Deputy head Saron Urding believes that partially selective schools offer a noticeably different experience for teachers than comprehensives, because of the aspiration of students and the expectations of parents.

“This aspiration promotes self-challenge and independence, where learning becomes about a wider experience,” he says.

“Wider social and cultural knowledge, wider reading and the understanding of knowledge in different contexts are all features of this experience.”

Ashlawn pupils selected on their performance in the 11-plus exam are automatically placed into a “grammar stream” alongside those who have shown an aptitude for modern foreign languages. They all study separate sciences, further mathematics and two foreign languages, in addition to the core academic curriculum.

Mr Urding insists that the school, which has been described as a “comprehensive grammar”, champions “the third way of partial selection that seeks to benefit all”.

But, for some, the concept of having a “grammar stream” within a school seems divisive. Zoe Johnson-Walker, head of the Winston Churchill School, in Woking, Surrey, admits that some people found the word “grammar” difficult to deal with when she recently introduced streaming to her partially selective school.

“I think some people are challenged by the word ‘grammar’,” Ms Johnson-Walker said. “I think it’s a bit of an issue. We are trying to say, ‘You can all be the best you can be.’”

‘I think some people are challenged by the word “grammar”. It’s a bit of an issue.’

The school, which has an annual intake of 300 pupils - 8.6 per cent of whom are selected by ability tests and 5 per cent on aptitude for music - is now in its second year of streaming (see ‘We don’t want to pigeonhole children on ability’ box, below).

And the head believes that the system has been attractive to prospective employees. “I think teachers are excited by it because we are doing something different,” she says.

But it is clear that there is no one-size-fits-all model for partially selective schools. Some use mixed-ability classes or sets instead of streams. And one anonymous head of a hybrid school tells TES that their academic ability test has no effect on pupils or teachers - as no one is told who has got into the school by passing it.

“We don’t want there to be a grammar stream or a different expectation of these pupils,” the head says. “I am not interested in labelling kids on one test.”

The head admits that, being a partially selective school, it is harder to explain the admissions process to prospective parents, and there are costs involved in getting the tests marked. But apart from that, he says, the effects of the different status are negligible.

“It feels very much like a normal school. I don’t think it makes any difference on our results,” explains the head, who has also worked in comprehensives.

But if the differences between a comprehensive and a partially selective school are barely noticeable, then why do these schools still exist? The answer, overwhelmingly, is because of their popularity with parents. Partial selection allows families to access schools without being restricted by a catchment area, or by a particular faith.

Pressure from parents

“Teachers and headteachers often don’t want to do it but it is hard to get rid of it as parents want it,” reveals an anonymous head of a partially selective school, who wants to abolish its entrance exam.

Jo Myhill-Johnson, associate principal at King Edward VI Academy, in Lincolnshire - which selects almost a third of its pupils on general ability - says: “By removing [the grammar school element] we would not want people to think that our aspirations and standards differ greatly from the many grammar schools in the area.”

And if, as heads say, parents are drawn to schools with academic tests, then the government’s Green Paper could open up the doors for even more hybrid schools in areas where there is local demand.

The “third way” proposal already has the backing of Toby Young, the new director of the government-backed free schools charity New Schools Network, who has called for schools to be allowed to select 25 per cent of places on the basis of ability.

But the growing evidence that selection doesn’t improve social mobility may deter headteachers from altering their admission policies. Ability tests have been widely criticised for putting children from poor backgrounds at a disadvantage because their parents cannot afford to pay a tutor to help them prepare.

Then there is the potential that selection could have a negative impact on neighbouring comprehensives.

Asked if she would consider making more of her intake selective, Ms Johnson-Walker, whose school is in a non-selective area, says: “We are part of a bigger community so we would have to look at the impact on other schools.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters