Did Gove ruin Greening’s shot at greatness?

As I am sure you know, “status quo” is a phrase that means the existing state of affairs. What you may not know is that “status quo” is itself a shortened version of the original Latin phrase “in statu quo res erantante bellum”, meaning “in the state in which things were before the war”.

Michael Gove was certainly happy to wage war on “The Blob” as education secretary. In contrast, his successor, Nicky Morgan, swiftly replaced his hyperactivity with pretty much zero activity during her entire two years in office as she defended the status quo while pretending that the war had never happened in the first place. Having two diametrically opposed predecessors left Justine Greening in an awkward position when she was appointed in July 2016. With the election now out of the way, it is pertinent to ask what we have learned in the past 11 months about the kind of education secretary she wants to be.

With the newly beefed-up Department for Education (universities were being reintegrated) at her fingertips, Justine Greening had little time to settle in last year before some big decisions arrived on her desk.

Within a matter of days of taking up her post, she disappointed many by delaying the national funding formula outlined several months earlier by Morgan. A couple of weeks later, grammar schools hit the headlines for the first time in around 20 years when it was reported that Theresa May was considering their reintroduction.

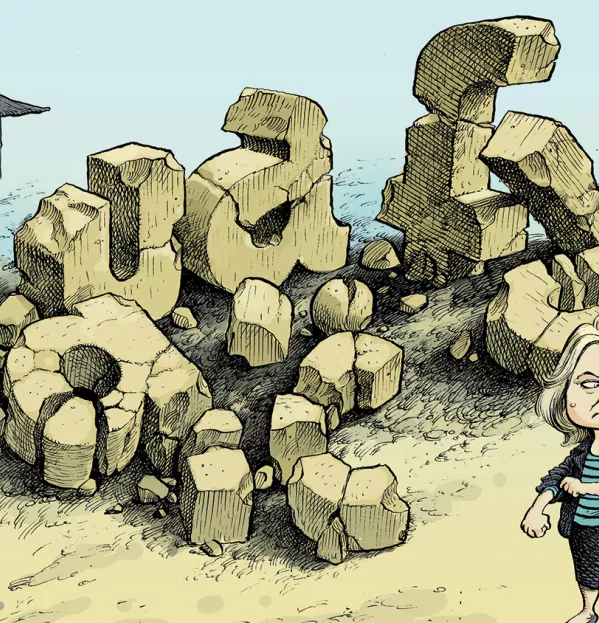

The ensuing storm has dogged the comprehensive-schooled education secretary ever since. It was immediately apparent that Number 10 was the driving force behind the push for more grammar schools, yet the DfE was passed the responsibility for making it happen. After a bruising opening period, Greening turned her attention to less glamorous but still significant policy areas. She dropped Morgan’s plan to eliminate reserved places for parent governors (“parents are part of how success gets delivered”) as well as abandoning the aim that all schools would become academies by 2020, saying that the DfE’s efforts would instead be focused on improving schools. Given this change of tack, it was no surprise to see her consign the entire education bill published by Nicky Morgan in March 2016 to the scrapheap. Dropping a proposed piece of legislation will always draw criticism from its supporters as well as embolden its critics; it was, nevertheless, the right call.

U-turn if you want to

Given the magnitude of the decision to abandon an education bill, amid the heated debate over grammar schools, one would have forgiven Greening for avoiding thorny issues for a while. On the contrary, she kept plugging away at whatever came in her direction. Labour MPs led a campaign against funding cuts for training young apprentices, and Greening decided to acquiesce to their request in October by announcing an extra 20 per cent payment to training providers. Even though this was a sharp policy U-turn that handed her political opponents an easy and very public victory, Greening figured that the best thing to do was to back down.

This was brave and bold in equal measure, but still paled in comparison with the subsequent decision to scrap a 2015 election manifesto commitment to force all pupils failing reading and maths assessments at the end of primary school to resit them in their first year of secondary school.

While forced resits was undoubtedly one of the worst education policies in living memory, breaking election manifesto commitments is a dangerous road for any minister to take (just ask chancellor Philip Hammond).

Far from stopping there, the secretary of state announced in March that national curriculum tests for seven-year-olds in England would be axed and replaced with teacher assessment of four- and five-year-olds, signalling the emergence of a more considered approach to when and why pupils are tested. Making sex education compulsory was yet another stunning reversal, given how this subject had been left quietly sitting in the corner for years.

From what we have seen, the common thread that runs through all of the judgement calls that Greening has made is “pragmatism”. Taking more time over the national funding formula, lowering the burden of assessment in primary schools, providing greater financial stability for training apprentices, retaining parent governors, easing off on full academisation - while these decisions are open to debate when taken in isolation, they collectively demonstrate an immensely sensible and level-headed approach to any problem, crisis or complaint. Furthermore, we have seen that she does not feel in any way bound by the ideologies or policies of her forerunners.

Political stasis

What a shame, then, that instead of reaping the benefits of having a pragmatic and thoughtful education secretary, we are likely to see very little of what her talents could deliver in future. Whether it is fighting a desperate battle to save the national funding formula, attempting to reverse teacher recruitment shortfalls, tackling the excruciating overspends on free school sites, untangling the calamitous apprenticeship reforms or being the public face of real-terms cuts to education budgets across the country, the new political reality may result in political stasis.

Whether this happens or not, Greening has done an impressive job so far. Through the incremental changes and tweaks that she has made to a variety of policy questions, she has begun to dampen the febrile atmosphere in education politics and set us on a calmer, more measured path.

Imagine what our education system would look like now if in 2010 she, instead of Gove, had been given the chance to think through how we could put the building blocks of an evidence-based, high-performing education system in place and how we might deliver it. Regrettably, her time and her department’s resources are now likely to be expended on clearing up the immense cumulative mess that she has inherited rather than on setting her own agenda.

That is why I can’t help but worry that Greening, even taking into account her recent reappointment, may be the best education secretary that we’ll never have.

Tom Richmond is a teacher and former adviser to ministers at the Department for Education. He tweets @Tom_Richmond

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters