‘The excesses in salaries will bring down the whole programme’

The power of academy trusts to set their leaders’ salaries encapsulates the huge amount of freedom - and responsibility - they are handed upon leaving local authority control.

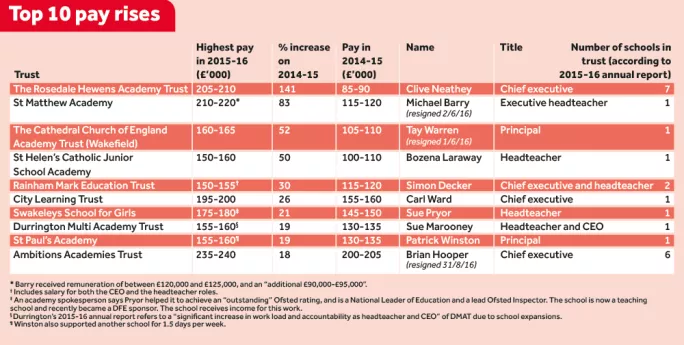

Offering the right salary for the right person, and paying enough to keep them, is no easy task - especially at a time of squeezed public finances. But amid these budgetary pressures, England’s top-paying academy trusts are approving annual pay rises of up to 141 per cent, according to a Tes analysis.

Justifications for large pay packets vary, but academies often cite the number of schools run by an individual, or the fact that a trust has expanded. However, these explanations do not always tell the whole story, judging by the annual accounts of the 121 academy trusts named by the Department for Education as paying at least one employee in excess of £150,000 a year in 2015-16.

Our analysis shows little correlation between the pay of academy leaders and the size of the trusts they lead. In fact, many leaders earning more than the prime minister’s salary only run a single school.

About one in four (24 per cent) of the 150 best-paid academy bosses enjoyed double-digit pay rises in 2015-16, and almost half of those enjoying inflation-busting increases ran trusts comprised of a single school.

Shadow education secretary Angela Rayner sees the pay rises as evidence of a “fragmented, unaccountable school system in which there is too little meaningful oversight of how millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money is spent”. She adds: “From the huge increases in related-party transactions (see page 17), to senior MAT (multi-academy trust) staff seeing their salaries skyrocket as most teachers face another year of real-terms pay cuts, the government has serious questions to answer”.

The 150 academy leaders in our analysis earned £179,000 a year on average in 2015-16 - 19 per cent more than the prime minister’s salary. The figure has risen sharply since 2014-15, when it was £161,000.

In some cases, leaders have been paid two salaries for substantial, separate roles. For example, Rainham Mark Education Trust’s Simon Decker was given a 30 per cent pay rise last year, after taking on the roles of headteacher and chief executive officer. He is stepping down as head from next September.

Another trust in the DfE’s list was St Helen’s Catholic Junior School in Brentwood, Essex, which has about 350 pupils. In 2015-16, its headteacher, Bozena Laraway, was paid between £150,000 and £160,000 - a 50 per cent rise on the previous year, which she says reflects the consultancy support she gave to another school during that time.

The Cathedral Church of England Academy Trust, based in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, had 664 pupils on roll in 2015-16. Its former principal, Tay Warren, was paid between £160,000 and £165,000 - a 52 per cent increase on the previous year.

Clive Neathey, chief executive of the Rosedale Hewens Academy Trust, which runs seven schools, received the biggest percentage increase. He saw his pay soar to between £205,000 and £210,000 in 2015-16 - up by 141 per cent on the previous year.

Beverley Amos, the chair of trustees of the Rosedale Hewens trust, says that the figures are “misleading”. She says: “The fact of the matter is that Mr Neathey had previously made a decision, in the interests of the trust, to effectively take a significant pay cut at a time when the trust was expanding by commissioning a number of new provisions.”

In 2014-15, in a year when the trust took on an extra school, Neathey was paid £85,000-£90,000. This was down on the previous year, when the academy chain had six schools and paid Mr Neathey £110,000 to £115,000. The year before that, in 2012-13, the trust took on three new schools and he was paid £180,000-£185,000.

Neathey worked “pro bono” on “at least three capital projects in order to safely establish our new schools within the funding envelope,” Amos adds.

Although Sir Dan Moynihan, chief executive of the Harris Federation, tops the list in terms of his actual salary, which was £420,000 in 2015-16, it rose by a comparatively small 6 per cent that year.

As Rayner’s comments demonstrate, the scale of pay rises is leading to broader questions being asked of the entire academies programme. Sir Michael Wilshaw, former Ofsted chief inspector and a strong supporter of academies, fears that this could lead to the academy movement being derailed due to “reputational damage”.

He says: “The DfE has clearly lost control. Public money is not being spent well and the excesses that we’re seeing in relation to salaries will bring down the whole programme unless the DfE gets a grip.”

Sir Michael stops short of calling for a cap on salaries, something recently suggested by academy pioneer Lord Adonis, but says there needs to be closer scrutiny of year-on-year rises.

‘Wild West’ of pay

Whether or not the salaries of the top-paid academy bosses are justifiable, they certainly stand in marked contrast to the restrictions placed on teachers, who have endured a 1 per cent pay cap - effectively a pay cut - for seven years. And, as Tes revealed earlier this year, teacher salaries are falling further and further behind those at the top of the profession.

Teaching unions are now demanding a salary hike of 5 per cent for teachers to help redress the real-terms losses in pay suffered in recent years. Chris Keates, general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union, describes the figures revealed by Tes’ analysis as “deeply concerning” and blames the government for creating a system “that encouraged a culture of paying headteachers and school leaders what they want, and teachers what you can get away with”.

Keates’ comments reflect a perception by some that the world of academy pay is effectively a Wild West, with little oversight or control over how much is paid.

However, the DfE maintains that academies “operate under a strict system of financial oversight and accountability, with robust intervention when things go wrong”.

Regarding pay, the department adds: “It is essential that we have the best people to lead our schools if we are to raise standards.”

Boards of trustees must ensure that their decisions about levels of executive pay “follow a robust evidence-based process and are reflective of the individual’s role and responsibilities”, the department adds.

But just how “robust” are these processes? Guidance may be in place, but many believe it needs to be strengthened.

Sir Michael thinks it would help if Ofsted was granted powers to inspect academy central trusts in the same way it looks at local authorities, which the inspection body has said it would welcome.

In the meantime, Association of School and College Leaders deputy general secretary Malcolm Trobe sets out a more general rule that trusts may want to bear in mind. He says: “It is important that trusts that employ leaders on very high salary levels are able to explain the reasons for these decisions and are able to demonstrate good value for money”.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters