Flip the system

The youngest children at Barnsole Primary School are still in nappies and arrive with comfort blankets. Today, four of those fledgling pupils have wedged themselves upright into a short fabric tunnel and they are being steered across the room by a fifth - a boy in a space helmet.

“It is education,” says Peter Elliot, the early years professional who leads the class. “But it is embedded in their play.”

Indeed, thanks to sandpits and rocket ships, these children all make good progress.

Barnsole, in Gillingham, Kent, is one of a growing number of schools in England that take two-year-olds. The thinking is simple: early years education is proven to make a difference to outcomes, so if you can get children engaging with it from an earlier age, you can have a bigger impact on both their short- and long-term success.

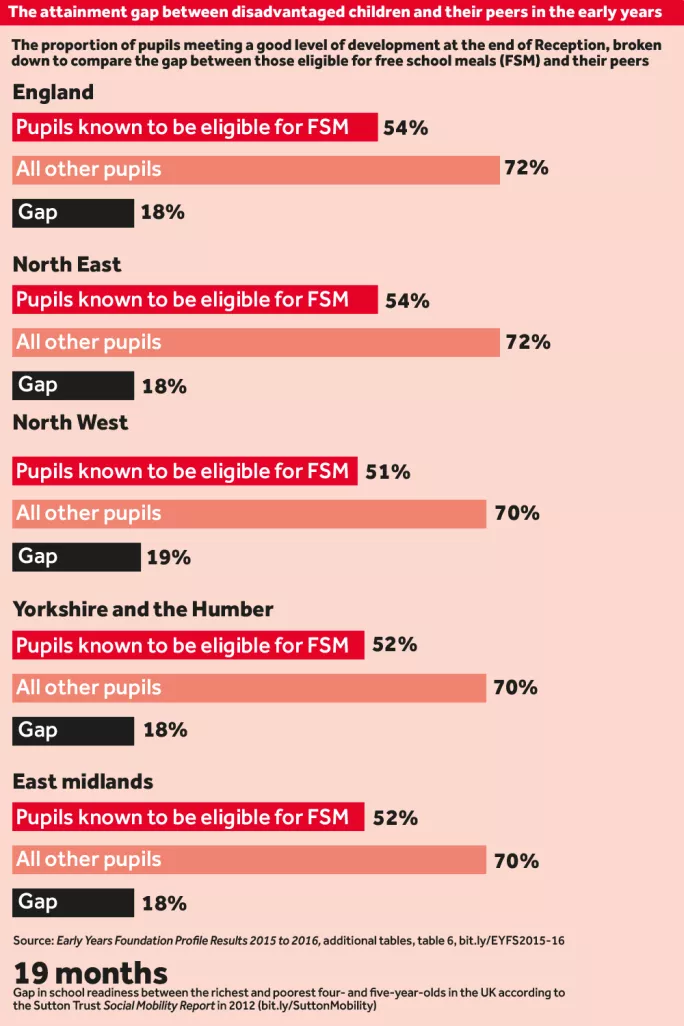

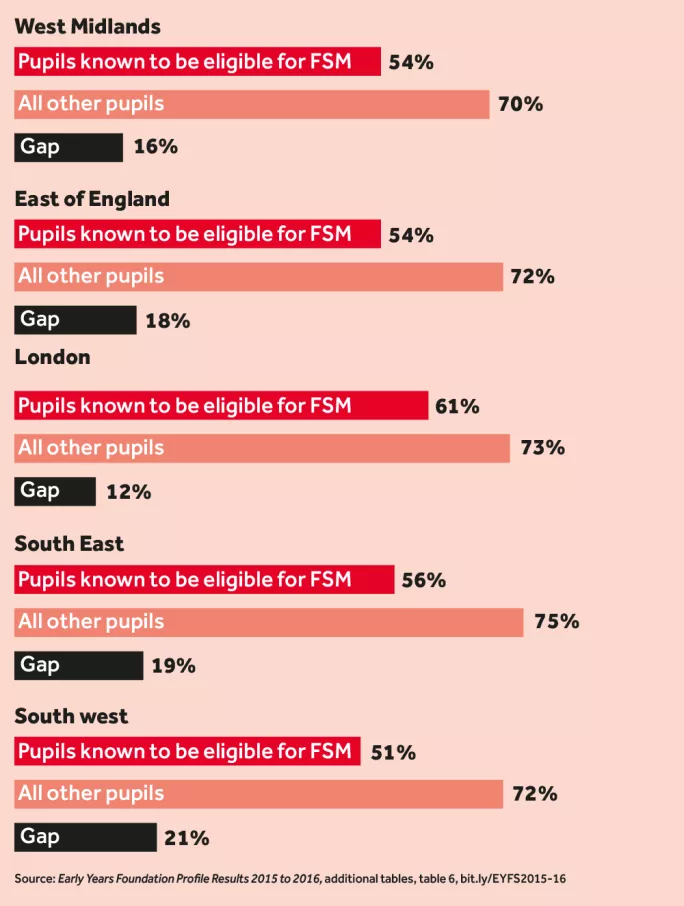

For disadvantaged children in particular, the early years can be essential. The 2012 Sutton Trust Social Mobility Report found a 19-month gap in school readiness between the richest and poorest four- and five-year-olds in the UK. In 2016, 54 per cent of children eligible for free school meals were at a good level of development by the end of Reception year, according to teacher assessments. The figure for all other children was 72 per cent. The disparity persists throughout school. But research suggests you can do much to close the gap if you get children into high-quality early years education.

‘Early childhood education is the most efficient way to build a highly educated, skilled workforce’

“There’s emerging evidence that, particularly for disadvantaged children, people giving them a chance to get a flying start in early learning is one of the best ways to close the gap,” says Sir Kevan Collins, chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation.

So strong is the evidence of both short- and long-term impacts, you would think that early years would be the star of the education show. That ministers would obsess over it, teachers flock to work in it and money flow towards it. But that doesn’t happen.

Instead, politically it is often an afterthought, in teaching terms it is regularly derided as “childcare” or “babysitting” - sometimes even by those in the teaching profession itself - and funding levels do not reflect the importance it seems to hold.

The sector is flourishing despite these restrictions, but how much better could outcomes be for all children - especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds - if the restrictions were lifted?

Or what if we pushed it even further: how far could pupil outcomes ultimately be improved if we turned education upside down and shifted our bias of focus, money, monitoring and prestige from the end of school life, where it has been concentrated for so long, and bestowed it instead upon the very start?

The forgotten sector

The advantages of early education are so clear that in September 2015, the United Nations made it a global goal for all children to have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education.

Meanwhile, the influential Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) study has found that the effects of attending a quality preschool are still evident in a student’s results at age 15.

And in England, the Effective Provision of Preschool Education (EPPE) project, which was set up to track 3,000 children as they entered school, found that, at age 7, those who had attended preschool did better than those who hadn’t. The effect was particularly significant for the poorest pupils.

“While not eliminating disadvantage, preschool can help to ameliorate the effects of social disadvantage and can provide children with a better start to school,” the report says. “Therefore, investing in good quality preschool provision can be seen as an effective means of achieving targets concerning social exclusion and breaking cycles of disadvantage.”

Indeed, you can find a plethora of research showing that early years interventions work. For example, the Perry Preschool study in Michigan, US, which began in 1962, found that, by the age of 15, the disadvantaged young people who had attended the programme were less likely to show delinquent behaviour and did better at school than their peers. Another study followed a total of 1,400 children through the Chicago-based Child-Parent Center programme and schooling until they were 28, finding that attending preschool was linked to higher educational attainment and income, and lower rates of imprisonment or drug use.

But how important is the sector when compared with other phases of education?

The Heckman equation looks like a children’s slide. It starts off, high up on the left-hand side, and curves down to the bottom right. It is perhaps the most famous slide in early years. It shows that the earlier a dollar of investment is made in developing a person, the higher the rate of return.

The equation is named after James J Heckman, professor of economics at the University of Chicago and Nobel laureate. He has researched the economics of early childhood development and is director of the university’s Center for the Economics of Human Development.

‘So far, we have had only evolution and not revolution’

“All children need quality early childhood development from birth to age 5, but disadvantaged children are least likely to receive it and should be the first to receive subsidies from the government,” according to the key findings section of the centre’s website. “Early childhood education is the most efficient way to provide the tools for upward mobility.”

Similarly, the introduction to the Early Years Foundation Stage, which sets out what is taught in England’s preschool sector, states: “Every child deserves the best possible start in life and the support that enables them to fulfil their potential. Children develop quickly in the early years and a child’s experiences between birth and age 5 have a major impact on their future life chances.”

So, early years education is clearly very important for educational outcomes and, according to some, it might well be the most important phase of education.

Which makes the current attitude to early years in England rather confusing.

In terms of policy, the profile of early years has been rising, but although it was a key issue in the last general election, it seemed that the main parties were all vying over who could do the most for parents (by offering free childcare), rather than who could do most to improve the educational attainment of their offspring. And the sector could be forgiven for thinking that, between elections, even that level of interest wanes.

Meanwhile, Caroline Dinenage MP handles the ministerial briefs for equalities and women, as well as early years. On her government website profile, the latter responsibility is listed last. The rest of the schools sector has a minister for school standards - Nick Gibb - who has no such divided loyalties with other briefs. Dinenage was also not announced until more than a week after Gibb and almost three weeks after education secretary Justine Greening. The role was a long way down the list of priorities.

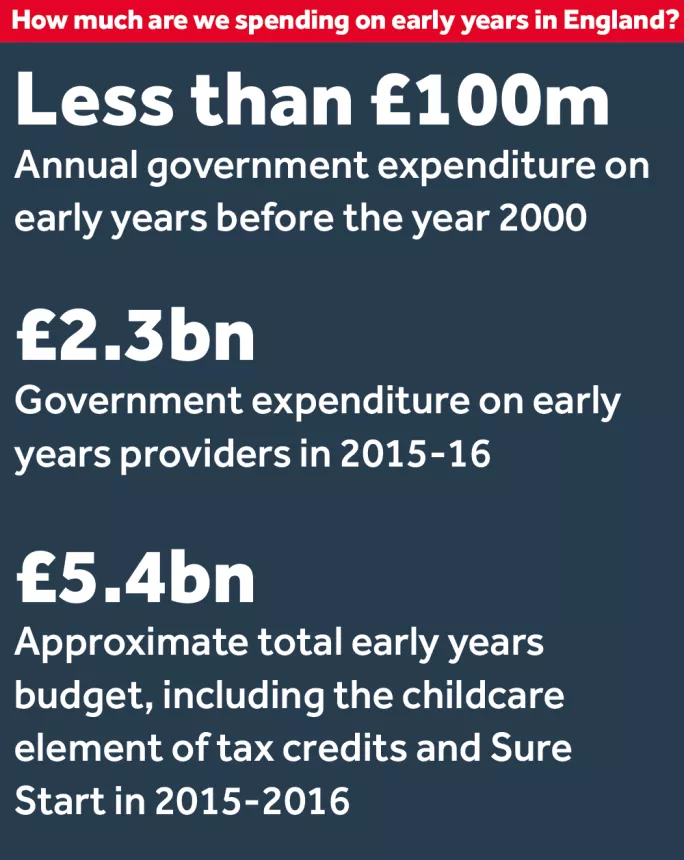

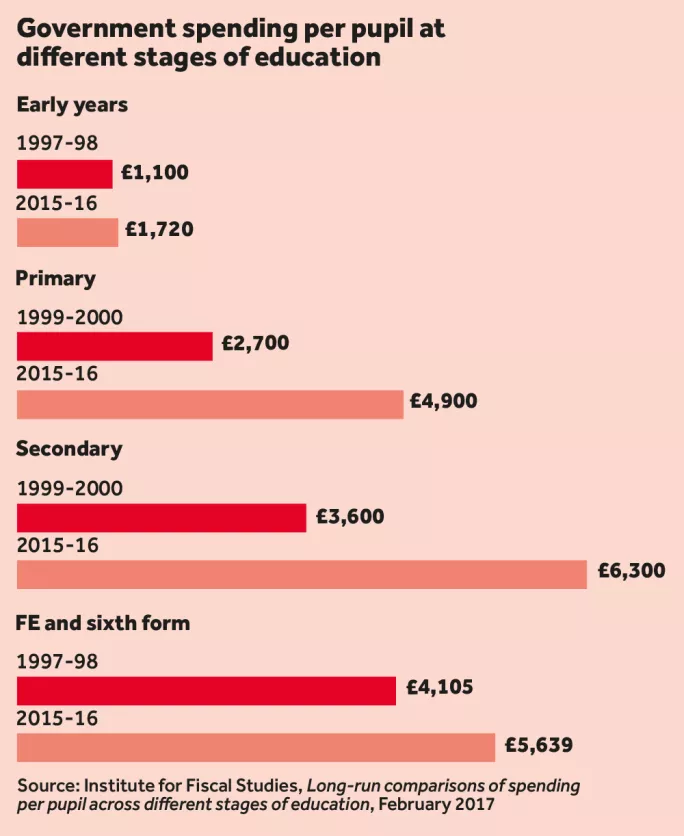

All this suggests early years is a bit of a political afterthought. As for funding, successive governments have invested billions in expanding the early years sector - but, in nurseries and preschools, there are anomalies that have not gone unnoticed. For example, the early years pupil premium for disadvantaged children is £300 - a third of that for a primary pupil. The NAHT headteachers’ union and National Governors’ Association have called for three- and four-year-olds to get the sames. In fact, the total amount of government spending, if broken down per pupil, is still much less in early years - and has risen by less - than in primary or secondary, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (see “How much are we spending on early years in England?” box, below).

In addition, the current plans to expand the offer of free early education from 15 hours to 30 hours for three- and four-year-olds with working parents are causing concern. The Preschool Learning Alliance, which represents 14,000 providers, says that the new funding rates are based on “flimsy” data and are too low to allow settings to meet the demand for places. “The government likes to boast that it is investing more than ever in the early years sector, but the fact is more funding is not the same as enough funding,” Neil Leitch, chief executive of the alliance, says.

This concern is shared by the National Audit Office, which last year warned that providers may choose to offer more hours to existing three and four-year-olds, rather than take disadvantaged two-year-olds, who require more staff per child - thus jeopardising the aim of narrowing the gap between disadvantaged children and their peers at age 5.

“While there is a lot of talk about the importance of early years, when I’m sat looking at our latest cash flow, it often looks more like rhetoric than reality,” says Sue Cowley, behaviour expert and chair of the management committee of an early years setting.

Lastly, there are the low levels of pay and respect for those working in the early years sector. In her review of early education and childcare qualifications in 2012, Professor Cathy Nutbrown referred to a “lack of understanding” of the role of early years staff. “Some appear to think that working with young children means nothing more than changing nappies and wiping noses. This is a misconception of what it is to work with young children and an insult to young children,” she wrote.

There has been a drive to improve qualifications - and understanding of the role. However, a 2015 report from the UCL Institute of Education looked at the childcare workforce outside schools and found a rise in the number of workers with A-level standard qualifications but no rise in pay. The average wage for a childcare worker was £6.60 per hour or £10,325 a year in 2012-14. In 2015, the average full-time equivalent salary for all full- and part-time teachers was £37,800.

Changing the game

Clearly something needs to change. So, say we turned education upside down. Say that, instead of focusing each summer on who received the Oxbridge golden ticket, celebrating those students with top GCSE results, and gasping at the six-figure salaries of those running multi-academy trusts, we decided that it was the achievements of four-year-olds that really mattered. That their teachers should be revered, and no serious teacher training was possible without understanding nursery practice. And let’s say we increased funding while we were at it.

If we did all this, what might we be able to do with early years to ensure it had the impact that research suggests it should have?

In some respects, it would be a matter of building on what is already there. Despite the fact that the early years sector has arguably been undervalued, it performs extremely well. The proportion of “good” and “outstanding” nurseries, preschools and childminders has risen for six years in a row and is now at 91 per cent, according to Ofsted’s most recent annual report. The proportion of “good” and “outstanding” nurseries in the least deprived areas is almost identical to that in the most deprived areas.

What we need to do is to push that quality further and ensure all provision is outstanding, according to the Education Endowment Foundation’s Collins.

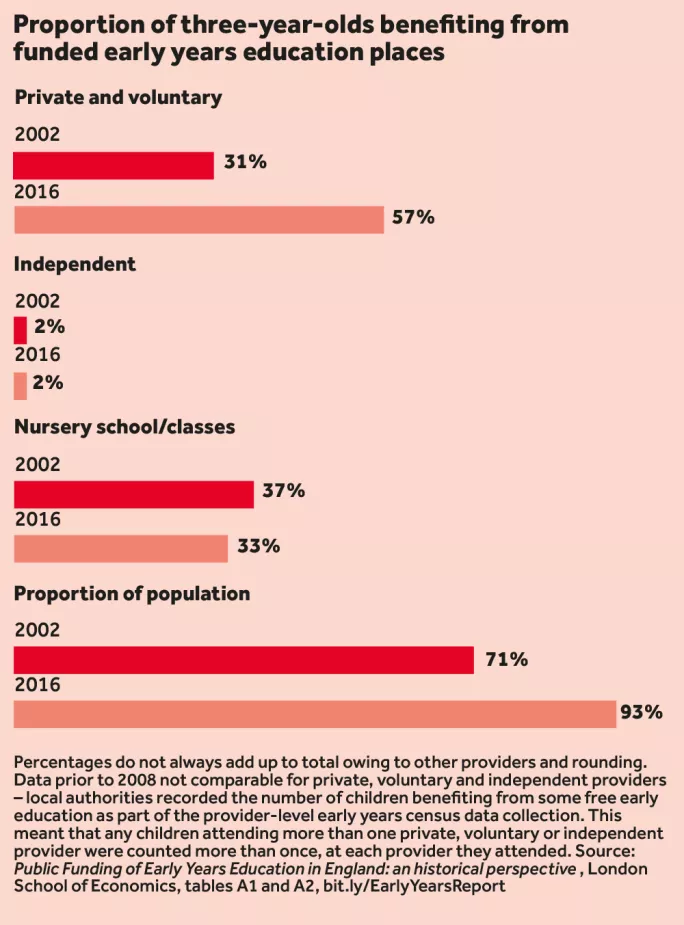

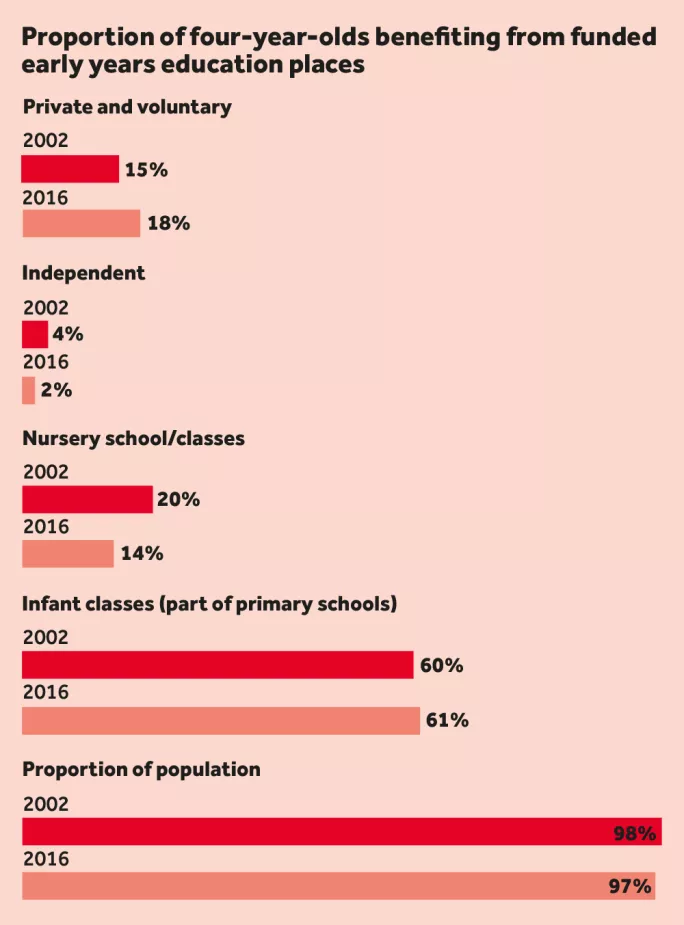

“I think the great thing in England has been the focus on access,” he says. “We are getting a huge proportion of kids at 3 and 4, even now at 2, into opportunities for learning. But what we haven’t done is reap the benefits of that properly, particularly because we haven’t invested in quality in the way that we should. The focus has been on access rather than quality. To me that’s a huge priority.”

How do you increase quality? The EPPE study found that children made more progress in preschool centres where staff had higher qualifications, particularly if the manager was highly qualified.

‘It’s not simply a matter of redirecting funding to early years because all of childhood is a special time for learning’

“Having trained teachers working with children in preschool settings (for a substantial proportion of time, and most importantly as the curriculum leader) had the greatest impact on quality, and was linked specifically with better outcomes in pre-reading and social development at age 5,” researchers reported.

There is evidence that maintained nursery schools, which employ teachers, do better.

“Our view, based on numerous studies, is that we should have that ambition for early education to be teacher-led,” says Kayte Lawton, head of UK policy at Save the Children. “There is a good case for ensuring every nursery, every group setting, should all be led by a teacher or someone with an appropriate early years teaching qualification or early childhood degree.”

With better funding, that would be possible. But do all early years settings really need a teacher? Or would a graduate specialising in early years be as good, possibly even better?

A recent study from the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics found that counting how many staff have degrees, or teaching qualifications, may not be the best way to measure quality. The researchers used information from 2008-11, covering 1.8 million children, to analyse the qualification level of staff present in the setting and working with the children.

Overall, they found that while there was an association between attendance at nursery provision where a graduate was working and children doing better in their early years profile results at the end of Reception, the effect was “extremely small” - just one third of a point higher, where the total number of points is 117.

The researchers conclude that raising the number of qualifications may not be a simple mechanism to raise quality.

Teacher quality matters for outcomes, they say, but you cannot necessarily measure that through readily measured factors such as qualifications.

If teacher qualifications are not the route to improved quality, then perhaps a more radical approach is needed.

“I think that some of the pressure points in the system arise from the fact that, so far, we only have had evolution and not revolution,” says Eva Lloyd, professor of early childhood at the University of East London. “We traditionally have had these separate strands of early education, childcare and social welfare provision and they don’t sit very comfortably together. We should question these ancient divisions in creating a different system.”

There certainly are schools that are trying to shake up early years provision more dramatically. These institutions are looking at ways of basing health and social care services on school grounds and ways to have those professionals working more cohesively with educators. The idea is to have an integrated approach to tackling any disadvantage children may be experiencing - similar to how Sure Start Children’s Centres work. These attempts are proving challenging for multiple reasons - but with a sudden influx of political goodwill, money and prestige for early years, perhaps those aims could be met.

But even with all these things in its corner, an early years system overhaul to increase quality - or simply to increase qualified professionals in the sector - would require overcoming some complex problems.

The first is judging value for money. At the moment, children’s attainment at age 4 or 5 is measured using the Early Years Foundation Stage profile. The profile is an assessment of 17 areas, including reading and maths, as well as social skills, carried out by teachers at the end of the Reception year, which is the final year of the foundation stage. But there is no routine link with the early years settings that children have attended, meaning it cannot be used to assess the type of providers that have the most impact.

The lack of data has concerned MPs on the Commons Public Accounts Select Committee, who raised the issue last year. The committee pointed out that there was no mechanism for identifying how councils used their centrally retained funding, or what they did to ensure there were enough places to meet demand, and that there was a lack of data on the impact of free childcare.

‘There is a really strong case, a compelling case, for more investment in earlier years of schooling’

In response, the government said that it was looking into how best to assess pupils. This month, it has published a workforce strategy for the early years sector, which includes developing a programme that specifically seeks to grow the graduate workforce in disadvantaged areas. A longitudinal study is also tracking the impact of early education on two-, three- and fouryear-olds, with a final report due in 2020.

But, quite simply, if the government were to put all its focus on early years, it would need better metrics for scrutiny of the system than it currently has. Devising those metrics would be difficult and highly controversial, and that would be tough to overcome.

The second problem is that England has a complex early years sector with a patchwork of maintained nurseries and private, voluntary and independent preschool provision - and, of course, childminders. That complicates funding, logistics and many other factors that would need to be considered.

The third problem is finding the money. The education budget is limited, so who would we take money off to boost the coffers of the early years sector?

Perhaps one way would be to look at outlay later on. In 2014-15, £725 million was spent by universities to improve access to university among students from low-income families and other under-represented groups. Perhaps some of this could be better diverted to early years to help disadvantaged students get the grades they need? But this is not an argument that goes down well with universities.

“There is a really strong case, a compelling case, for more investment in earlier years of schooling,” says Sir David Greenaway, vicechancellor of the University of Nottingham. “But it would be odd to fund that by reducing the expenditure that universities are making [in this area] because it will take several years to deliver and we need to be doing things for those students who are coming through from low-income backgrounds now.”

Raids on primary or secondary funding at a time of incredibly tight budgets would likely be met with similar reactions.

And finally, there would be some kickback from the sector itself if the eye of government swung too far in the direction of early years, bringing the kind of pressure that is driving staff out of schools.

All our eggs in one basket?

Perhaps the biggest barrier, though, is that far from everyone is convinced early years is deserving of more attention than any other phase of schooling - robbing resources from other sectors or giving early years all the limelight doesn’t stack up for some.

Paul Howard-Jones, professor of neuroscience and education at the University of Bristol, points out that learning is complicated. You cannot simply intervene at age 3 and then be confident the child will stay on track until 18.

“Yes, the brain is more malleable when children are younger,” he says. “Yes, there is good evidence to show that some early interventions can be extremely effective and their effects are long-lasting. But it’s not simply a matter of redirecting funding to early years because all of childhood is a special time for learning.

“Development is not continuous and there is not one single mental ability which develops in the same way during childhood. Some parts, like reasoning, keep developing until around age 19. We don’t know enough about what are the most effective interventions to say when you should do them and we should not just jump to the conclusion that it is always better to introduce every aspect early.”

‘I keep coming back to the need to do something at every stage’

Lee Elliot Major, chief executive of the Sutton Trust, is also sceptical.

“I’ve been looking at this for years and I keep coming back to the need to do something at every stage,” he says. “You probably need to do things pre-birth, even. Clearly, early years is crucial. We have documented gaps in attainment at age 5. But if you don’t do more stuff with those children then they will come back to the trajectory they would have been in if you didn’t do anything in the first place.

“You have to have sustained intervention, even if you do something in early years you have to follow it up with school and I think you still need to do university access work.”

There’s another argument against, too. A focus on early years could do only so much - to make a real difference, you need a society-wide intervention.

Heckman’s research suggests it is non-cognitive social skills that matter for success both in school and later in life. He says that even if cognitive skills, such as reading scores, fade in the short-term, the gains in socio-emotional skills will create academic and social outcomes in the long-term.

And when you are talking about boosting children’s emotional and social skills, you need to start thinking about supporting their parents, not just with childcare but through family support services, health services and employment.

That is what the Sure Start Children’s Centres do - building on a history of integrated centres - providing support not just for the child in front of them but for the family behind the child, and this support is particularly crucial for disadvantaged families. Unfortunately, austerity has led to these services being drastically cut back: since 2010, 313 children’s centres have closed.

The direction of government travel seems to be away from the integrated approach that experts say we need.

A little R-E-S-P-E-C-T

But turning education upside down to shine a light on early years would not necessarily have to be about robbing other phases of attention or cash. Instead, it should be more about levelling the playing field. Currently, early years gets little attention - by shifting the focus, we could help it to catch up.

This should be a universal aim, particularly among teachers: clearly, we want all young children to have access to excellent education. At the moment, it seems that we’re aiming to achieve this at the lowest possible cost, with minimum attention politically and in an environment where early years professionals are unfairly looked down upon as “inferior” educators.

Let’s be clear: the early years sector is doing an amazing job despite all these barriers. But how much better could it be if we all gave it a bit more respect, a bit more time, a bit more attention and, most of all, a bit more money?

At Barnsole Primary, there is a lovely book corner with bookshelves-themed wallpaper and a curtain to hide yourself away - and all of it is paid for by the staff. Here, commitment, a sense of duty and moral purpose are in as plentiful supply as they are in any other phase of education.

Indeed, the teaching may look different but this is education just as much as what goes on in primary or secondary - and it is proven to be effective - so isn’t it time we started treating it that way?

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters