How to rewrite the rule book for reading lessons

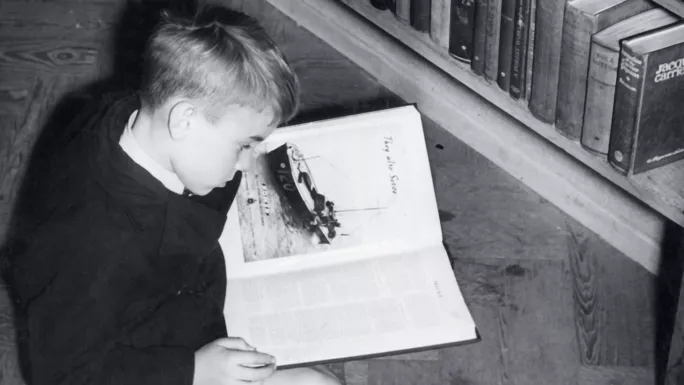

When Peter started primary school, he did not know what an elephant looked like or what a spade was.

“He couldn’t read and be engaged because of his lack of experience,” says his P1 teacher, Emma Richardson. “You take it for granted that children are having the same experiences you had as a child and are coming to school with the same knowledge as the rest of the class, but sometimes that’s just not the case.”

But then one day Peter came into school with a dinosaur. He knew everything about it: its name, what it ate and the names of a vast array of other dinosaurs.

Ms Richardson phoned Linwood Library and asked them to set aside as many books about dinosaurs as they could. Ultimately, it was the Harry and his Bucket Full of Dinosaurs series that got Peter hooked.

“He identifies as a reader now,” says Ms Richardson, who teaches at Our Lady of Peace Primary in Linwood, Renfrewshire.

This is crucial, says University of Strathclyde literacy expert Professor Sue Ellis, who has been working with Renfrewshire primaries on the three essential elements - or “domains” - that must be included in literacy teaching if pupils are to become readers, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Teachers must be aware of the knowledge and skills readers need, including being able to judge their level. They need to bring pupils’ experiences outside school into school so they can put the right texts in their hands and build their identity as readers - simply, for instance, what kind of books do they like?

Before Ellis and University of Strathclyde colleagues started working with Renfrewshire primaries, it might have been assumed that a child like Peter, who was struggling to read, needed more focused support, or to go at a slower pace on the reading scheme, says Julie Paterson, Renfrewshire’s literacy development officer. The question of whether or not he was enjoying what he was reading might have been missed.

“Taking an interest in him opened up a fantastic selection of books,” says Paterson. “He now sees the value in reading and sees it can be something interesting and enjoyable.”

Class divide

All children come to school with a backpack of knowledge, but only the middle-class ones are asked to unpack it, says Ellis. Whether a child knows all the flags of Europe or details about every Pokémon, schools need to tap into that knowledge to turn them into readers. Pupils’ persistence is low when they do not enjoy what they read, she warns.

Ellis continues: “Reading is not just about what’s written on the page, it’s an interaction between what you know and what’s written on the page. Unless a child in poverty gets that experience fairly regularly, they are never going to feel that reading is for them.”

Too often local authorities rush to buy quick-fixes but the focus has to be - as in Renfrewshire - on upskilling teachers, says Ellis.

So far the authority has invested £900,000 and more than 800 primary and secondary teachers have taken part in professional development about the teaching of reading.

Paterson adds: “The Renfrewshire approach is not a resource-based approach, so it does not require specific materials or resources in school. Education has been inundated with resources that promise the world, but it is our teachers that will lead the way and help us close the attainment gap.”

When the scheme launched in 2015-16, it was “quite a traditional professional-development course”, says Ellis, with one teacher and the head from every primary attending once a week. “The most important element was teachers and headteachers working with people expert in teaching children to read and scoping the issues together, and then working out the biggest pay-offs,” says Ellis.

The teachers were asked to “team-teach” a child who was struggling to read for 10 weeks.

“That child became a lens to see the curriculum through - why had it not worked for that child? What needed to be done in the future?” says Ellis.

The teachers applied that learning to all their pupils, with support from university staff via classroom visits and face-to-face meetings.

In August last year the literacy approach was rolled out and standardised reading tests set. The tests were sat again in May this year.

The results show a “significant rise” in attainment, says Ellis. A recent evaluation for the council identifies “a general shift of children out of the ‘very low’ and ‘below-average’” attainment groups.

The report continues: “In terms of improving children’s long-term prospects for wider educational achievement, this is an important result for Renfrewshire’s children. Literacy is a gateway to the rest of the curriculum, and children who struggle to read will find it harder to achieve their potential.” Renfrewshire education convener Jim Paterson says that the “cutting-edge” partnership between the authority and the University of Strathclyde has been key. He adds: “Supporting teachers to take children’s opinions and their knowledge and understanding of the world into account has helped more children to enjoy reading and will increase their chances of success in education and in later life.”

Some visible changes in schools include a shift away from traditional “round-robin” reading lessons where pupils are divided into groups and each child reads a page of a story. There is also more emphasis on pupils reading “real books” alongside reading schemes, so that they become familiar with a range of texts.

A love of reading

However, perhaps the biggest shift is the permission the new approach has given teachers to inspire a love of reading.

Renfrewshire’s Todholm Primary won this year’s Scottish Education Awards prize for raising attainment in literacy. It has introduced an outdoor reading area, a weekly bedtime story session for P1s and their parents, a reading café for P2s and 3s and their parents, and it started its own book festival.

Lesley-Anne Dick, headteacher at Our Lady of Peace Primary, says the changes that have been introduced “seem obvious” but that such an approach in many ways goes against the way teachers are trained to “work your way through the reading scheme and everything is done for a reason or a purpose - it has to fit some outcome”.

Now, however, “we read to the children - novels, or stories for the wee ones - at least once a week. From Easter, P1 was reading real books, rather than just the reading scheme”.

The formula, she says, is simple: “The more they read, the more they want to read - and the better the progress they make.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters