How a Scout troop is helping special school pupils flourish

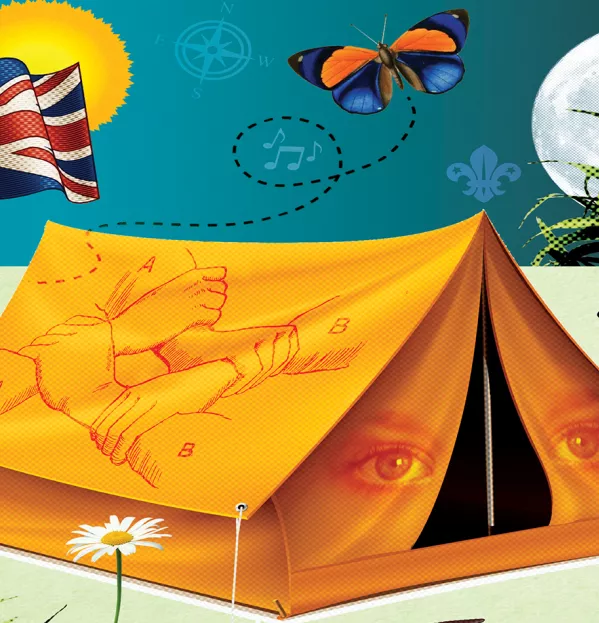

Adventure, risk-taking, a break from the cosseted comforts of everyday life: these ideas are central to the Scouts. And, increasingly, they are playing out on a grander scale: while the furthest my Scouting days in the 1980s took me was Templars’ Park on the outskirts of Aberdeen, last month I was in touch with a Scout leader who was about to embark on an expedition to Malaysia with 56 teenagers.

But the scale of adventure is not measured purely in miles travelled. Adventure - “an exciting experience” and “the spirit of enterprise”, as The Chambers Dictionary defines it - is about breaking out of the reassuring or deadening norms of everyday life, and getting a shot of vitality as you do so.

A group of children at one school know exactly what that feels like. Just before the summer, six P7s in West Dunbartonshire officially became Scouts in what was, for Scotland, the culmination of a unique trial.

Since October last year, the six pupils at Kilpatrick School for children with complex additional support needs (ASN) had been taking part in weekly Scouting sessions at the school. And at the end of the academic year, their achievements were recognised as they each received their Scout “neckie” and were invested into the global movement - with staff reporting that there “wasn’t a dry eye in the house”.

The school, with a pretty backdrop of the undulating Kilpatrick Hills, has 170 students up to the age of 18 years, who have a wide range of complex needs. But its focus has shifted in recent times.

As depute headteacher Victor Cannon explains, there has been a move away from the language of bases - such as an “autism base” or a “severe and complex base” - as staff place more emphasis on what pupils can do than on what they cannot. Many take National 3 qualifications, and one boy recently took an N4 in hairdressing and is now at a further education college.

Cannon has a background in secondary teaching, having trained as a business education teacher, but he feels he has found his niche here. He loves the “ethos as soon as you walk in the door - very positive, nurturing”. Even so, he admits that there was some concern about bringing Scouting to the school, and that it might not work for Kilpatrick pupils.

As not everyone even knew what the Scouts were, preparation included watching an excerpt from the Disney-Pixar film Up - one of the main characters is a Scout.

There was immediate excitement, especially about camping, but this was tempered by staff who knew that some pupils had tried Scouts and it had not worked out. Some had found it hard to sit and listen in echoey Scout halls with unusual smells, and got mixed up when given a series of instructions that they could not piece together.

“Different things could set them off with their anxieties, and there’s just too much - it’s overstimulating for them,” says Kilpatrick teacher Kate Abbott. “For a lot of our children, it’s just not possible to access [Scouts] in a mainstream environment.”

The first day of the Scouting sessions was on 31 October last year, and it got a bit chaotic at times. Staff will tell you with a wry smile that, in hindsight, Halloween perhaps wasn’t the best time to start, given the fancy dress and the excitement levels that came with ghosts and witches wandering the corridors.

The initial ambitions had been reined in, at least temporarily. Staff had talked about a large group of pupils being involved, across a range of ages. But just six P7s - five boys and one girl - began their Scouting experience that day: the plan was to start small and, if the experiment was successful, to build from there.

Pitching the idea of camping

At what point did staff really think it might work? For Cannon and Abbott, who teaches P7, it was when the pupils went camping in a small play-tunnel that you might find in a nursery, designed to resemble a bee with black and yellow stripes and wings on the top. For their camping trip, this tent was taken a few dozen steps away, to an outdoor area at the school.

“They particularly loved when they went outside camping,” says Abbott. “They were in that tent for 10 minutes but, in their minds, they were camping - they love that because a lot of our children don’t get that kind of experience.”

Scouting sessions now start with an incessant mantra of “Are we camping today? Are we camping today?” The pupils have fond memories of songs, campfires and marshmallows toasted over candles. And they have relished doing things that seem a bit more risky than usual. One boy in particular, who is often very withdrawn, was “just laughing and loving it” during racing games and, in an unusually social act, held another boy’s hands.

There is a balance to be struck: routine is important in the school but pupils love being able to do the same sort of things as older siblings and children in mainstream settings. Kilpatrick and other special schools (see box, right) have, therefore, become more inclined to offer programmes such as the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award in the final few years before students leave school.

In March, three former Kilpatrick students, who took part in the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme at the school, competed at the Special Olympics World Summer Games in Abu Dhabi - one as a cyclist and two in sailing.

“That’s a big part of what we want for our children here at Kilpatrick: to be part of and feel part of their communities, and to work with organisations that other young people in mainstream settings would automatically get the opportunity to do,” says headteacher Louise McMahon.

Older students’ successes with schemes such as the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award have persuaded staff to venture into similar territory at primary level. They hope that the Scouts programme can, for example, help pupils through one of the potentially most fraught experiences in school: transition.

“Transitions are really difficult for our young people,” says McMahon, but the Scouting group is “a really settled class and they’re excited about moving on in the school”, she says, adding that the Scouts “has been part of that jigsaw”.

The school is looking to expand the scheme each year: the plan is that this first cohort will carry on with the Scouts until they leave school, and every new batch of P7s - and perhaps also P6s - will start the same journey.

For McMahon, it all ties into a key principle at the school: “Our children learn best when they’re active and engaged.”

The Scouting sessions take place within the school grounds but they feel different to other activities and lessons, says Abbott. “They see it as something special, something important, and they know that they are the only ones in school that get it.”

The children love seeing the male Scouts leaders arrive in their Scouting gear; most staff at the school are female. And when they make the Scouts promise with three raised fingers - a physical feat that can feel like the “hardest thing ever” to some - “there’s pride [in doing it]”, she adds.

Gary Ward, a development officer for the Scouts in the Paisley and Renfrewshire area, says there is now “a strong, meaningful connection” with Kilpatrick School and that “Scouting has become an integral part of the week for the young people”, leading to improved behaviour, an appreciation of the outdoors and plenty of learning through play.

The pupils also “love a routine”, and an important one in the Scouts is the raising of the Union flag, which a class helper of the week gets to do. “They love the flag. It’s their favourite thing - they all want to do that,” says Abbott.

Routine adventure

Some activities have been calibrated over time. The Scouts promise, for example, was a “bit over their heads” so the simpler and shorter Cubs promise is now used. They do not change into Scouts uniforms - other than the neckies they now own - because cost is an issue and many pupils find it tricky and stressful to get in and out of different clothes. There is now an established routine: flag, promise, badge work and an activity.

Staff started talking to pupils about the Scouts from August last year so that they would begin the sessions with some awareness and would know something about how they might gain a Scouts badge. The five badges used - artist, chef, gardener, international and naturalist - have turned out to be one of the strongest hooks into Scouting. For the chef badge, despite the group including children on the autistic spectrum who are usually very fussy about food, they have tried lots of new dishes and created vivid memories, such as the contortions their faces performed when they tasted the tartness of cranberries.

Working toward the badges has required - among other skills - exploring healthy and unhealthy foods, cookery, learning about other countries, identifying the flora and fauna around them, pitching tents and literally getting their hands dirty looking for worms, woodlice and spiders.

“To see the children explore and engage in the different badges through play has been exceptionally rewarding,” says parent helper Ann McGuinness. “Their social skills and resilience are amazing and they should be so proud of themselves.” She adds that “the best part by far is the laughter and fun we all have every week”.

Abbott says the teamwork and camaraderie of Scouts have had a big impact. The pupils tend to struggle at working together and taking turns, but she has seen some “absolutely lovely” vignettes. The initial chaos of games involving balls, beanbags, throwing and chasing gave way to something else as the penny dropped about the need to work together. One “big lovable guy” took another pupil under his wing and showed him what to do, and “suddenly this relationship bloomed, which was just lovely to see”.

Abbott says of one pupil: “I think that he’s suddenly discovered friends. I know that sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it? He’s been in the same class as them for years. But I think, with the different activities and games they’re doing that perhaps he’s not done in the playground or PE, that he’s having to be involved in these games. I think he’s realised that there are people in the class, that he’s got friends - for a long while he didn’t ever bother with other children.”

McMahon says it is crucial that Kilpatrick pupils, like other young people their age, have experiences that are “part and parcel of growing up” - the school has a similar motivation for embracing Scouts as it does for organising a prom every two years.

Community ties

Kilpatrick is also determined to build more links with the local community: McMahon was surprised after joining the school at how many local residents had never set foot on the grounds. Teaming up with local Scout leaders and running a cafe in the school, then, are both ways of “ensuring that our young people stay connected to their communities”.

The special sector has, as Tes Scotland has documented, often felt marginalised. As Abbott puts it, sometimes there is a feeling of “mainstream gets this, this, this and this, and we’re the forgotten few”.

The project with the Scouts, therefore, is one way of making sure the school and its pupils are not tucked out of sight in their little corner of West Dunbartonshire.

Now, indeed, there is talk of taking the work to an ambitious new level: of moving some of the Scouting activity out of the school, so that pupils can work and play directly with other young people in local Scout groups.

“They would love it,” says Abbott. “Most of our children are very sociable, would love to be with other children, to be part of a bigger, wider group. They would love that - absolutely, without a doubt.”

Henry Hepburn is news editor for Tes Scotland. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

This article originally appeared in the 30 August 2019 issue under the headline “Be prepared (to see pupils with additional needs flourish)”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters