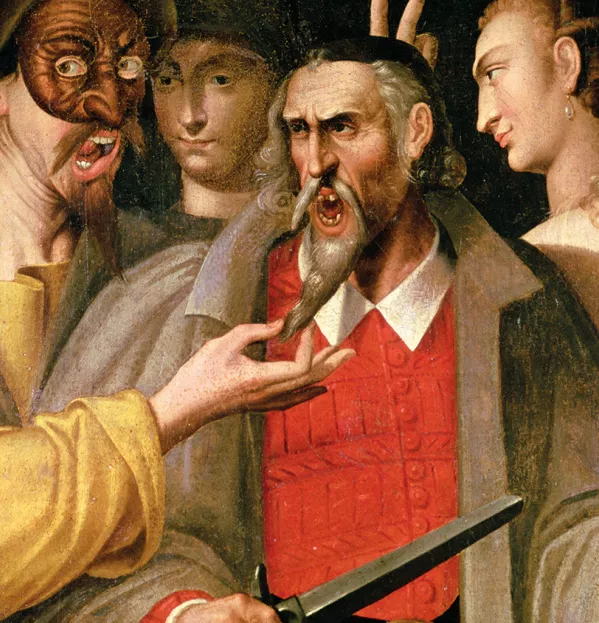

It’s vital to keep a civil tongue in your head

Hands up if you think a senior colleague has been rude to you? OK, quite a few of you. How about if there has been a time when someone above you in the hierarchy has been offhand or dismissive? Yes, some more there, I notice. And for those of you who’ve been in the job for some time: has this got worse over the years? Thought so.

You are not alone. The Harvard Business Review reports that rudeness in the workplace is on the increase, and a lot of us who work in schools will recognise this. Incivility causes damage. The research, based on the opinions of 800 leaders, found that workers who had been on the receiving end of incivility:

* Intentionally decreased their work effort (48 per cent).

* Intentionally decreased the quality of work (28 per cent).

* Said their commitment to the organisation declined (78 per cent).

* Left their job (12 per cent).

* Admitted taking their frustration out on customers (25 per cent).

I recently shared these findings with a group of open-minded colleagues. We recognised all the outcomes, but it was the final statement on the list that really made us think.

Although some in education are unhappy with students being called “customers”, the terms are interchangeable here. Disturbingly, some members of the group were aware of colleagues who had, in some way, taken out their frustration with leadership incivility on the children in their class - a case of the persecuted always kicking downwards.

As leaders, do we appreciate the emotional impact our behaviour has? What we are talking about here are “leadership dispositions”. For the purposes of this article, I will define dispositions as “qualities of mind and character that influence behaviours”.

Identifying leadership dispositions should be the starting point for any organisation (Veland, 2012), and I think we are at a time when leader behaviour needs to be reviewed because school leadership is changing.

Less than a generation ago, a school leader’s remit would have been leading within the school they worked in. It was unusual for a senior or middle leader to have a field of influence that went very far beyond the walls of their school. This is no longer the case.

The introduction and expansion of multi-academy trusts, along with less formal school alliances, has led to a growth in system leadership. This has resulted in senior leadership teams advising and training colleagues in different schools, which requires an evolving set of dispositions.

Not only is this type of leadership increasing, it also appears to be populated by a significant number of new leaders.

Research suggests that inexperienced leaders tend to struggle with “more subtle relationship” issues (Bunker, Kram and Ting, 2002). They can find themselves at odds with more experienced colleagues. So perhaps a different set of dispositions is needed for newly appointed leaders.

While we could draw up a long list of desirable dispositions, in a 2010 paper in the Academic Leadership Journal, Carroll Helm focuses on five.

Humility

This is often defined as having the courage to admit when you are wrong and to be upfront about it. Leaders who have this disposition tend to foster relationships built on trust. They find it easy to ask for advice from other colleagues no matter what level they are in the hierarchy. The senior leader who hasn’t had to plan a lesson for years and asks for comments from those who do it on a daily basis will be more respected than one who imposes a new planning strategy from above.

Honesty

Addressing problems with an open mind and without personal prejudice, and giving clear, waffle-free answers will help colleagues know where they stand. Being kept in the dark about the reasons for decisions can eat away at people. Trying to convince everyone that there isn’t a behaviour problem when there clearly is will only do damage in the long run.

Empathy

This doesn’t always have to mean trying to take on other peoples’ emotions in an attempt to please everyone all of the time. It is about the thoughtful consideration of others’ feelings (Goleman 1996).

I know two local schools that had poor inspection outcomes four years ago. One headteacher told staff that this would mean possible job losses and said to expect more lesson observations. The other met with colleagues in their classrooms, where she asked how they could go about improving things together. The second school is now classed as “good”. The first struggles to keep any decent staff and the outcomes are not as positive.

Fairness

Judgements should not favour a particular group or individual. Nothing destroys morale quicker than a leadership team member’s friend being given preferential treatment. Being allocated the toughest Year 9 groups while the head of middle school’s mate got the easiest still sticks in my memory - and it was a long time ago.

Integrity

Having strong moral principles seems obvious, but there are leaders who don’t show this disposition. Gaming the exam system and allowing cheating in Sats are examples we have seen, but this runs much deeper. Narrowing the curriculum, anyone?

Guidelines on leadership dispositions do exist. The 2015 National Standards of Excellence for Headteachers includes “Domain 1”, which, it can be argued, is a set of dispositions. Meanwhile, the General Teaching Council for Scotland has an “interpersonal skills and abilities” section in its 2012 Standards for Leadership and Management.

It is well documented that the culture of a school is shaped by its leaders. If those at the top cannot be civil, fair and honest, how can they expect everyone else to be? As usual, the best leaders lead by example.

Bill Lowe is a former headteacher, a visiting lecturer at Newman University and the University of Birmingham, and an education consultant working with Thinking Matters

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters