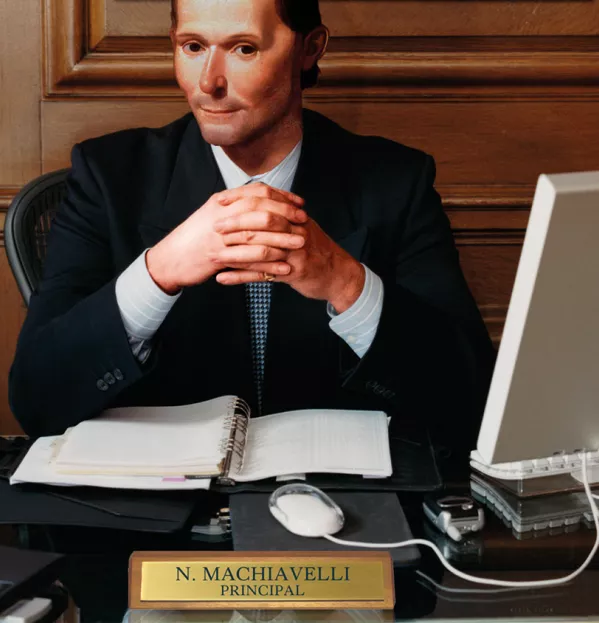

Machiavelli’s Prince becomes a principal in new FE satire

Machiavelli is enjoying something of a renaissance in political discourse. Former education secretary Michael Gove was described as a “Machiavellian psychopath”

by supporters of Boris Johnson, after he undermined his erstwhile ally in the unseemly battle for the Conservative Party leadership.

US president Donald Trump’s colourful behaviour has also repeatedly been likened to the traits associated with the notorious Renaissance statesman and philosopher.

In his best-known work, The Prince, Machiavelli argues that it is necessary for rulers to employ ruthless cunning and duplicity and, where necessary, to be prepared to act immorally. It is, he concludes, “much safer to be feared than loved”. Isaiah Berlin attributes to Bertrand Russell the view that The Prince is “a handbook for gangsters”. According to a new book, it might also be regarded as a handbook for college leaders.

Published next week, The Principal: Power and Professionalism in FE is a collection of essays on the theme of leadership in further education, examined - tongue firmly in cheek - through the prism of The Prince.

The book is edited by: Joel Petrie, an FE lecturer and doctoral researcher at the University of Huddersfield; Maire Daley, a former lecturer at City of Liverpool College; and Kevin Orr, professor of work and learning at the University of Huddersfield. Contributors include FE professionals such as Rob Peutrell and Simon Reddy, along with academics specialising in further and adult education, including Gary Husband and Professor Ann-Marie Bathmaker. The book is the long-awaited sequel to the popular Further Education and the Twelve Dancing Princesses, published in 2015, which called for an end to FE being described as the “Cinderella sector” and replaced the metaphor with another of the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, The Twelve Dancing Princesses.

The Principal offers a darker vision of the sector, albeit one with utopian flashes of promise, should it manage to “steal back its fire from any authority that limits its agency to transform”. Frank Coffield, emeritus professor at the UCL Institute of Education, pays tribute to the new book’s “disturbing comparative studies, unsettling, critical research and deliciously subversive irony”, while Lynne Sedgmore, former executive director of the 157 Group, describes it as a “direct and provocative challenge to every principal and senior leader in FE”.

In this extract, Carol Azumah Dennis sketches out some of the less virtuous traits of college leaders who prefer to describe themselves as CEOs

There is a difference between calling yourself a principal and calling yourself a chief executive. If you are an accountant who has become a college leader after a successful career as a merchant banker, you may well wish to be known as a chief executive. After all, when you attend the local chamber of commerce meetings, “chief executive” is a title that your counterparts recognise and respect.

The 1990s managerial myth - that the management of public sector organisations is energised by professional self-interest - has created opportunities for a new type of college leader, one unencumbered by the luxuries of ethics. Being thus unencumbered has its advantages. Indeed, the situation that colleges now find themselves in might even demand it. In the absence of actual ethics, one thing that every college leader, principal or chief executive has recourse to is an ethical mantra that resonates powerfully across the sector with sufficient ambiguity to justify anything.

I would suggest that you develop and regularly use a mantra that has all the appearance of an ethical principle, but little of its content. It is wise to link this mantra to some distant educational radical - Freire and Dewey are good examples, but several others will do. Once the association is made, you may use, reuse and misuse this notion in as many ways as the situation requires. The mantra “Do the right thing”, coupled with an ethics of survival, will convince your staff, through love or fear, to descend with you to the depths of Hell.

It is hard to argue that cuts to provision are in the interest of students. Once their evening course has gone, they may never improve their life chances or attend a literacy class. The student may have no other social contact. Yet you must frame the choice thus: either accept a 60 per cent cut to provision this year or risk provision altogether next year. For the long-term future of the college, for your own reputation as a chief executive who makes hard decisions, for the sake of a six-figure salary; to implement a 60 per cent cut is to do the right thing.

Another cohort impacted by cuts is those lecturers and managers who remain in post. It may be to the detriment of staff to have their terms and conditions dramatically changed overnight.

There are now instances of staff who, in the name of flexibility, have no upper limits on their contractual teaching hours per year. This is to their personal detriment. Is it the right thing to do? Yes. Your college survey makes it clear: high levels of staff stress correlate with high levels of student satisfaction. This is unambiguous. The distress is worth it. We are here to meet the needs of our customers. The student is always right.

Any protest against these conditions of service must be silenced. This is the third and final beneficial use of the ethical mantra. It allows you to appear ethical, while remaining silent on the damage the policy does to your students, your staff, your college and the communities you serve.

You are earnest in your belief that you always do the right thing. It might be the best course of action when confronted with a series of unwholesome alternatives - even if those alternatives are never explicitly articulated. It is better to ignore any suggestion that a compromise we are prepared to live with - and can persuade others to live with - might not be the right thing.

This is an edited excerpt from The Principal: Power and Professionalism in FE, which will be published by UCL Institute of Education Press on 4 September

Carol Azumah Dennis is senior lecturer in education leadership and management at the Open University

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters