‘The missing subject after numeracy and literacy...’

You know your education system has gone drastically wrong when a lawyer, describing what he would do to his daughter or sister if they “engaged in premarital activities”, says this: “I would most certainly take this sort of sister or daughter to my farmhouse, and in front of my family, I would put petrol on her and set her alight.”

Brutal attitudes to woman (such as the above example from a case in India), shared by highly educated professionals and illiterate slum dwellers alike, are what have inspired documentary maker Leslee Udwin to start what she hopes will become a global education movement. And its first stop in Europe could be Scotland.

In 2012, the gang rape and murder of 23-year-old medical student Jyoti Singh in Delhi made worldwide headlines and sparked a month of protests about the lack of protection for women in India. In 2015, Udwin’s film about the case led to a global debate about sexual violence and rape culture. Months later, she came second in the New York Times “women of impact” list - those deemed to have made the greatest impact in the world that year - behind then US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

Now, Udwin is chief executive of Think Equal, an education programme that seeks to “end the discriminatory mindset and cycle of violence across our world” by creating a new school subject that fosters social and emotional learning from the earliest years.

The man quoted above, whose matterof-fact contemplation of violence against a hypothetical female relative, was a defence lawyer for perpetrators of Jyoti Singh’s rape and murder. On 16 December 2012, she had been on a night out with a male friend to see the film Life of Pi, after which they boarded a private bus. Six men on the vehicle raped her and beat her friend. On 29 December, Jyoti died of her horrific injuries.

The blame that the lawyer - and another defence lawyer who said “in our culture, there’s no place for a woman” - attached to Jyoti is proof, says Udwin, that education is no guarantee against barbaric attitudes.

During an exclusive interview with Tes Scotland in Edinburgh, prior to a showing of her film India’s Daughter, Udwin, recalls that the “commonality” in the rapists’ backgrounds was their lack of education, with only one having finished secondary school. “Then I realised that’s bullshit,” she says. “It’s nothing to do with access to education, because here are these lawyers who are eminently well educated, [with] the highest, finest degrees in the land.” She describes the lawyers as “worse than the rapists” because they shared the assailants’ disturbing views about women, but also carried great influence.

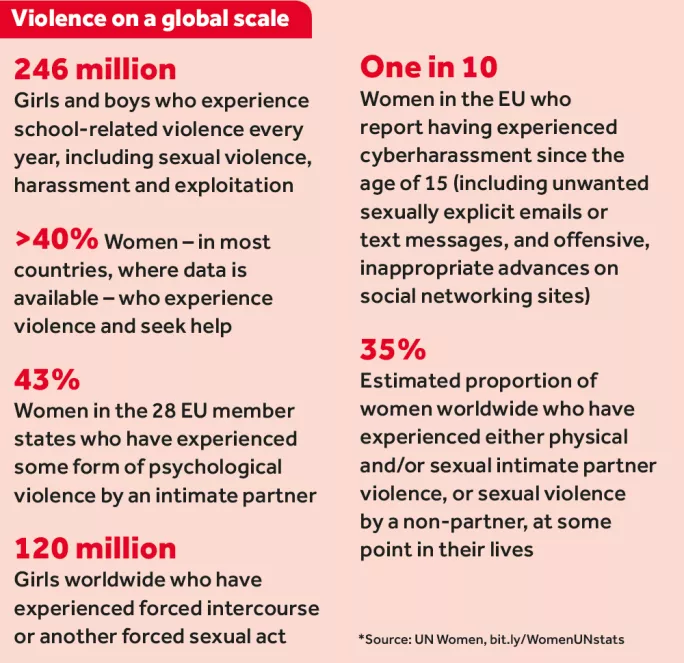

Udwin sees violence as being rife throughout the world, inflicted by people who see no value in their victims’ lives, whether they be perpetrators of genocide or a man she interviewed who said he had raped a five-year-old because “she was a beggar girl - her life had no value”. The two-and-a-half years spent making the film gave Udwin “absolute clarity” that the men who attacked Jyoti and showed no signs of remorse, and others like them, “are programmed by society to think as they think” by values learnt at a very early age.

Neuroscientific basis

Think Equal starts with pre-school education, from ages 3 to 5. This, she says, is when “the development of the human character takes place” - according to neuroscientists. Yet, around the world, “we’ve been treating those as years to be babysat”.

Udwin says education systems around the world are still largely designed to suit the utilitarian demands of the industrial revolution. “We live in a world which teaches that the main purpose of life is accumulation of wealth - all we’re doing as an education system is preparing our children for the labour market,” she says. “The purpose of education should be to prepare our children for life - to ensure they don’t get addicted to substances, don’t commit suicide, don’t abuse each other, don’t exclude and fear those who are different.”

An education system more focused on values, Udwin believes, is essential to inoculate humans against their tendency to violence. “How can we deem it compulsory for children to learn maths, but optional for a child to learn how to value another human being?” she asks.

The programme, which her organisation provides for free, was launched in Sri Lanka, where it has been made mandatory. Local policymakers in the country, says Udwin, calculate that the cost of the rollout in 19,500 schools will be the same as the cost of supporting 150 victims of domestic violence.

Pilots are also underway in Argentina, Botswana, Canada, India, Kenya and Singapore. Meanwhile, high-profile patrons include Malawi’s first female president, Joyce Banda, and Hollywood actress Meryl Streep.

Now, having heard about Scotland’s focus on the early years, Udwin finds herself in Edinburgh, preparing for a meeting with equalities secretary Angela Constance.

Constance later tells us that she welcomed the opportunity to meet Udwin. Violence against women, she said, was “a grievous violation of human rights” and the Scottish government was committed to tackling it. She added: “We know that education is critical to changing the attitudes and we are investing nearly £600,000 of funding to support the expansion of the Rape Crisis Scotland sexual violence prevention work in schools into an additional 11 local authorities.”

“Scotland will be the first country [to launch Think Equal] in Europe - I’m determined - and it deserves to be, because it really is enlightened,” says Udwin. The danger, she fears, is that Western countries are blind to the endemic violence in their midst. This is an “arrogant and complacent” attitude, says Udwin, as these nations, too, send insidious messages to children from an early age through, for example, the gender and power imbalance in politics and business.

Udwin says that she has already heard inspiring stories about the impact of the programme, which she describes as “the third, missing subject, after numeracy and literacy”.

One such example is of a fair-skinned three-year-old girl in Sri Lanka who would refuse to be fed by her dark-skinned maid. Using 35 narrative books and hundreds of detailed lesson plans, the programme sets out from the earliest age to show that, whether at work or play, differences in appearance are superficial.

Soon the girl was “caressing her maid’s arm, saying: ‘You have dark brown skin and it’s very beautiful - I have light brown skin, and it’s very beautiful.’”

As Udwin puts it: “The bottom line, wherever you are, is this: by 6, the character is set, the human being is cooked - but if they can be programmed at that age to be bad, they can also be programmed to be good.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters