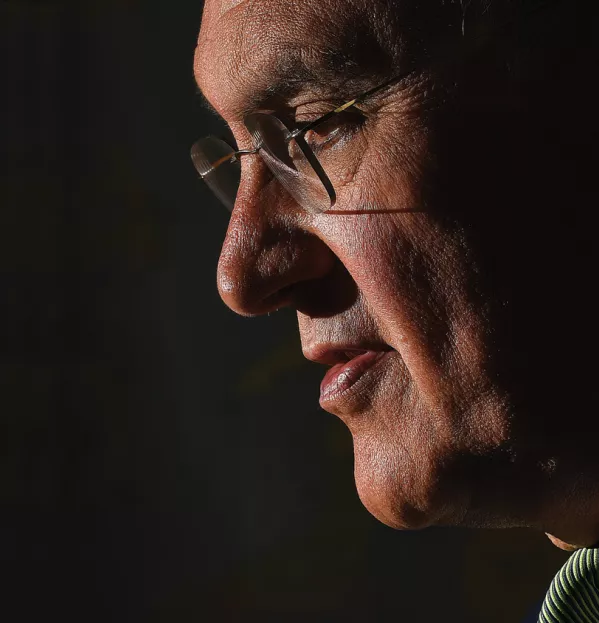

‘The nation’s headmaster’ bids farewell...

“Teachers don’t know what stress is, says Ofsted chief,” shouted one headline. “Teachers should roll up their sleeves and get to work,” screamed another.

It was May 2012 and Sir Michael Wilshaw, having only been in office for a few months, had just made a speech that would set the tone for what undoubtedly became a fractious relationship with the teaching profession.

Looking back now, that speech is the one regret the outgoing chief inspector has from his tenure running the watchdog. The only, single one.

“Knowing what I do now, I wouldn’t say that,” Wilshaw confides. “That stuff about stress, although I was hugely misquoted there, I probably wouldn’t say now.”

Misquoted or not, regardless, the incident was what brought home for the former headteacher the fact that his every utterance would be the focus of newspapers, social media and unions alike. From that point on, he would be in the spotlight.

“I could say what I liked as a head and it didn’t appear on the front pages of TES. You suddenly realised that you had to be guarded in what you said. And I learned that very quickly.

“I suppose if a question comes at me: have I made mistakes? Yes, I have. But the mistakes were borne out of naivety.”

This disclosure is a rare insight into Wilshaw, seldom seen by the public, and largely unknown to teachers.

Collision course

So often in his speeches or in his missives from Ofsted HQ, Wilshaw was unremitting in his demands of the profession, to the point where he ended up being dubbed “the nation’s headmaster” by the Daily Mail.

Often, this robust approach - parallels with his most famous predecessor, Sir Chris Woodhead, were hard to miss - set him on a collision course with other school leaders, who notoriously don’t take well to being told what to do, especially by Ofsted.

Geoff Barton, head of the King Edward VI School in Suffolk and a vocal critic of the schools watchdog, says Wilshaw gave the “impression of treating us all like delinquent members of his staffroom”.

The brusque nature of Wilshaw’s stewardship of the inspectorate is something that he does little to disabuse, and it is this attitude that snaps him out of any prolonged penitence in our interview.

“In terms of challenge, I don’t regret anything that I’ve done,” he stresses. “A chief inspector shouldn’t be doing the job unless they are prepared to challenge the education system to do better, but to also acknowledge where things are going well. Hopefully, I have done both.

“We have got to challenge complacency, we have got to challenge mediocrity and we have got to challenge failure where we see it. And if Ofsted doesn’t do that, who is going to?”

Any remaining embers of a mea culpa are quickly snuffed out. In an instant, Wilshaw is explaining just how Ofsted has made the lives of teachers easier, not harder. “If you are working in a good school with good leadership then you are going to have a pretty good life,” he adds.

In his mind, the job of running Ofsted worked in two ways, challenging the system to improve but also providing an independent running commentary on standards in schools.

“That’s why some people might say I’ve been too high-profile, or some of my critics might say I got into trouble by being too much in the press. I don’t accept that. My job is to tell the public what standards are like throughout the year. I don’t regret that bit at all,” he sniffs. Sitting in his office in central London, Wilshaw, in dark blue suit, crisp white shirt and green tie, is in a lively mood and appears undimmed by his years running one of government’s toughest agencies. He even smiles, every now and again.

During his five years at the helm, he achieved a great deal. He scrapped the “satisfactory” rating, replacing it with “requires improvement” - the reform that many heads say has done more to change mindset than any other.

He shortened the notice time for inspections, cutting it down from 48 hours to less than 24. He introduced a network of regional directors to give him better intelligence from each corner of the country. And, perhaps most importantly, he brought all inspectors in-house and ensured that every lead inspector was a serving practitioner from a good or outstanding school.

“When I started, we still had lay inspectors running around who had no experience of the classroom,” he points out.

Whisper it, but many of these reforms, especially to the inspection framework, are now winning positive reviews from many heads as they bed in.

Piled on his desk behind him is Sir Winston Churchill’s The Second World War collection, volumes 1 to 6. Volume 3 chronicles “The Grand Alliance”, which could easily be a description of his partnership with the then education secretary Michael Gove during the early days of his Ofsted career.

The politicians’ pal?

As head of the hugely successful Mossbourne Community Academy in east London, Wilshaw was headhunted to lead Ofsted by Gove, who, the chief inspector says, wanted someone “broadly sympathetic” to his reforms. Indeed, Gove had famously described him as his “hero”.

The controversial education secretary, who was in the middle of a once-in-a-generation raft of reforms, needed somebody who had credibility in the profession but also someone who represented “high-quality academy provision”, which Wilshaw did - with bells on.

The grand alliance of Wilshaw and Gove was an education reformer’s dream team - but, rather often, the partnership proved to be the scourge of headteachers across the country.

The pair pincered the profession, calling out schools for tolerating poor discipline and low standards, while extolling the benefits of the academies programme.

Both were committed to improving the life chances of the country’s poorest, no matter how many noses they bloodied in the process. This very close partnership was one of the reasons why Wilshaw’s relationship with classroom unions got off to a shaky start.

But then a very public spat in 2013 between the two - over Gove’s decision to replace the Labour-appointed chair of Ofsted, Baroness Morgan - soured their working relationship. At the time Wilshaw told the national press that he was “spitting blood” about what he saw as underhand briefings and unnecessary politicking.

“Michael,” Wilshaw says, looking back, “[is] a good man, a reformer and a man who wanted to do well by all children, particularly poor children - was badly advised by people who couldn’t keep their mouth shut. And who leaked and briefed in a way I found unprofessional, and I wasn’t prepared to tolerate that.”

The dispute led to a chilling of relations between Ofsted and the Department for Education, but also had a galvanising effect on the chief inspector. While Wilshaw was never afraid to “speak truth to power”, his clash with Gove appeared to steel him further.

With Gove’s departure in July 2014 went any allegiances Wilshaw may have had. From being the government’s cheerleader, he fast became one of its biggest critics. And, in turn, some of those who were most keen to have a go at him began to reassess the Ofsted boss.

He led a stinging criticism of the government’s push to turn every school into an academy, he clashed with the DfE over its plans to force every child to sit the English Baccalaureate, and he took ministers to task over the impact of the recruitment crisis.

In his most recent foray, Wilshaw condemned prime minister Theresa May’s plans to expand the number of grammar schools. He describes it as a “retrograde” move that he fears will mean that the country “forgets about the 80 per cent of children” who do not get into grammars.

As Sir Tim Brighouse, who was schools commissioner for London in the early noughties, says of Wilshaw, ministers “will be glad to see him retire”.

“At first [the profession] thought him too close to politicians, but in the end he found his ‘no-nonsense, tell-it-like-it-is voice’ and called them out whenever they indulged their many prejudices,” Brighouse says.

The chief inspector is clear that he was never “afraid” to speak his mind with either the education sector or government. But he says that any criticism of government policy has been rooted in his beliefs that have been formed over many years as both a head and classroom teacher. “When I speak out, it’s not just as Ofsted’s chief inspector but as someone with long experience of working in schools,” he says.

More than that, Wilshaw says he speaks out because, fundamentally, he cares. He cares if schools are doing well or not, because he cares that the children being taught in them may not be getting the best possible chance in life.

‘The gunslinger’

And it is that moral imperative - unsurprising from a devout Catholic - that drives him. Underneath the Dirty Harry persona, the Pale Rider sobriquet that he allowed to flourish, is someone who has a moral compunction to help the children that need it most. Just like every headteacher.

But the compassionate side is something, he believes, is often missed.

“I think it is. [Heads and teachers think] I’m too much of a critic,” he says. “But people who know me, I think, hopefully at the end of my tenure, people will say, ‘He did it for a purpose. He wasn’t doing it just for the sake of it - it was to raise standards’.

“I’m always conscious, and I used to say this to my staff, that children have just one opportunity. They don’t have it again. This is their one chance of getting a good education, particularly if they come from a poor background. That has been my driving force and my ambition: to make sure that children get a good deal. And if you’re a chief inspector who doesn’t have that at the back of your mind at all times - ‘children have just one chance’ - then you shouldn’t be doing the job.”

In his remaining two months as Ofsted chief, Wilshaw is intent on highlighting the reforms that have taken place over the past 20 years and how they have brought about great improvements to the country’s schools. The reforms that stand in opposition to the government’s grammar proposals. One last finger in the eye for government.

But now, at 70, he says, it is time for an “easier life”.

“Although I was speaking to [Conservative MP] Ken Clarke and he’s 76, isn’t he? And still going. And still being controversial and still falling foul of the prime minister,” he chuckles.

Life after Ofsted will be “less taxing and less high-profile”, but he is adamant that he will still be active in improving education. “Leadership is key,” he says, and he will be working with a number of institutions on leadership programmes.

And how does Wilshaw want his time at Ofsted to be remembered?

“I have been challenging, yes. I have been, from time to time, a difficult chief inspector and an abrasive one,” he admits. “But I hope people will say that my motivation was always to try to do best the by youngsters in this country and particularly poor youngsters. I hope people will say that about me.”

Share this article on Facebook or Twitter with #ToYouFromTES to be entered into a draw to win a TES digital subscription for 2017.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters