Nature vs nurture debate gets a blast from the past

Imagine that halfway between the two world wars, and then shortly after the Second World War, a country tested the intelligence of its 11-year-olds. Then, more than eight decades later, academics were able to explore how those same brains were performing in maturity - and whether education throughout their lifetimes had made a difference.

That is exactly the legacy of a pioneering University of Edinburgh educational psychologist who, in 1932 and 1947, amassed what remains the only record of IQ-type scores from entire age groups in any nation in the world. His work also provides a highly encouraging message for teachers: regardless of pupils’ genes, learning really can make a difference to the rest of their lives.

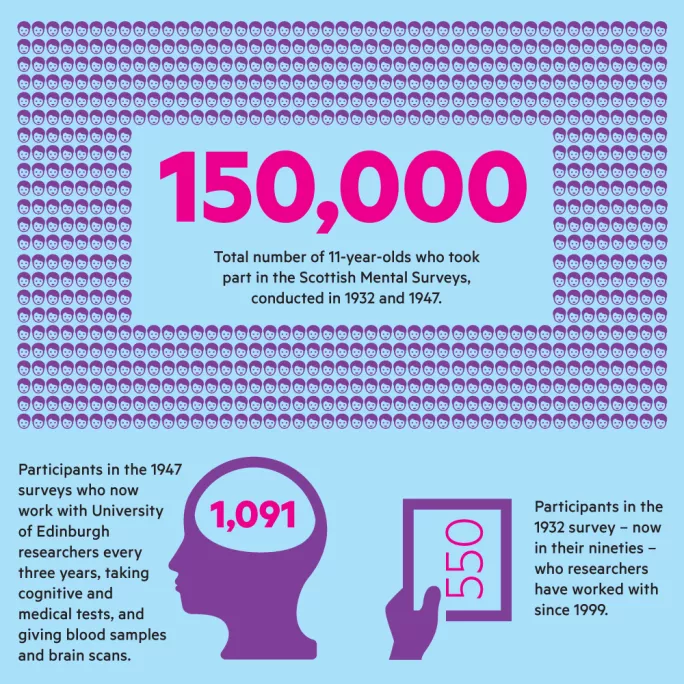

The work of Sir Godfrey Thomson, world-renowned in its day, has mostly been forgotten - largely because he was too modest to trumpet his own achievements. But a new exhibition at the University of Edinburgh library, exploring his life and work, is reviving interest. The show, which runs until the end of October, also explores how academics have spent the last two decades mining his unique data and tracking down more than 1,600 people who sat the original tests, known as the Scottish Mental Surveys.

Now in their eighties and nineties, participants in the study find themselves sitting tests every three years - giving researchers unique and “revelatory” data that helps them to deduce what keeps the brain fit and productive over a lifetime.

Some 150,000 children took part - almost every 11-year-old at school in Scotland in 1932 and 1947 - including George Mackay Brown, who became one of the country’s finest authors and poets, and actor Richard Wilson, best known for his Victor Mildrew character from sitcom One Foot In The Grave.

Sir Godfrey Thomson was ahead of his time in arguing the case for comprehensive schools in the 1920s - four decades before they made an appearance in Scotland in 1965.

He also made it his life’s mission to ensure that every child received equal access to educational opportunities; he hoped the tests would help pick out high-performers who might otherwise miss out on limited places at the country’s secondary schools.

Question of selection

The University of Edinburgh research underlines the dangers of definitively assessing children’s abilities at 11 - a topical issue amid strong speculation that Theresa May’s government could prompt the expansion of grammar schools in England. Findings show that people have “far higher” cognitive ability in old age than they recorded in childhood, according to Professor Ian Deary, who leads the research.

The findings also give great encouragement to teachers and lecturers, as they suggest that education can boost children’s life chances - regardless of the basic intelligence levels they inherited. This is at odds with other research by US scientist Robert Plomin, from Kings College London, whose work suggests inherited intelligence could account for nearly 60 per cent of a teenager’s GCSE results.

“Genetics plays a relatively small part of how much the brain changes with age, so by inference, the larger part is down to lifestyle and environment,” said Professor Deary. “So, if we ask what sort of environmental factors are associated with better thinking skills, it’s things like staying fit and active, having a healthy body, having more education.”

Learning more than one language and having a professional job that “makes you think a lot” have also been associated with better cognitive function in older age, he added.

Genetics plays a relatively small part of how much the brain changes with age

Professor Deary’s team has looked at social mobility across three generations, by asking people who sat the 1947 tests to share details about their parents and children. Their findings show that, while parents’ background was also a factor, “how much education you got” was strongly associated with “where you ended up in social position”; genetic factors accounted for only about a quarter of changes to people’s cognitive ability between childhood and old age.

The findings are “revelatory”, says Professor Deary, because they are a global one-off. While research has been done to track cognitive ability over time, none has the same span from childhood to people in their nineties.

The story of John Scott, 80, who took part in the 1947 survey, underlines how social environment can trump ability in determining how a life pans out.

“I wasn’t stupid - I was clever enough at school,” said Mr Scott. But he missed a lot of classes growing up in East Lothian because, as was common in his day, he would be excused from school to work potato harvests for up to eight weeks at a time.

“I was never much at school,” said Mr Scott, who undertakes extensive cognitive and medical testing at the university every three years. Like many boys at the time, he left at 15 to become a miner - in contrast with his 10 grandchildren, most of whom have gone on to study at university.

Godfrey Thomson: The Man Who Tested Scotland’s IQ runs until 29 October at the University of Edinburgh library’s main exhibition gallery

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters