Need peer-abuse counsel? Forget about your council

An incident in which a student is alleged to have sexually assaulted another pupil is a scenario that all teachers would rightly dread.

When such cases do unfortunately occur, dealing with them can be complex, so it is understandable that a school might seek support and counsel from its local authority.

However, Tes has established that nearly half of all councils do not provide any written guidance to schools on how they should deal with cases of peer-on-peer sexual abuse.

Charities have described the finding as “extremely worrying”, given the mounting evidence that sexual offences among young people are on the rise and widespread concerns that guidance issued by central government is insufficient.

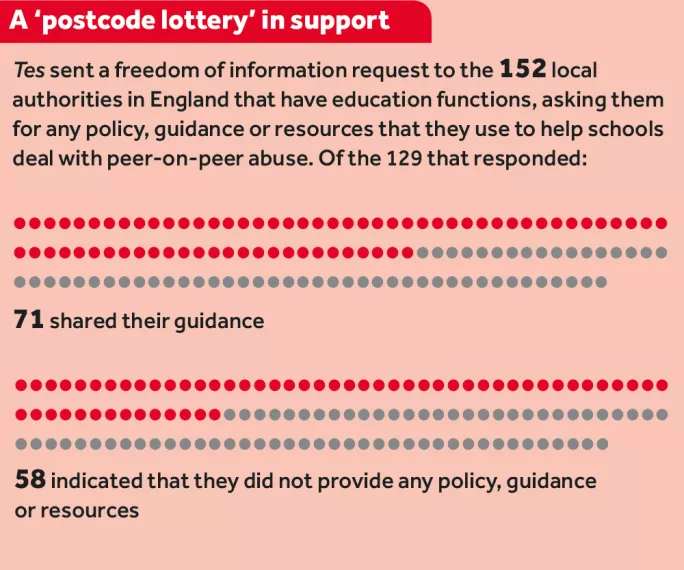

To make matters worse, councils in different parts of the country are offering conflicting advice, prompting concerns of a “postcode lottery” in how schools respond to cases of alleged abuse. Tes sent a freedom of information request to the 152 local authorities in England that have education functions, asking for any policy, guidance or resources that they use to help schools deal with peer-on-peer abuse. Of the 129 councils that had responded to the request by the time Tes went to press, 58 - 45 per cent - indicated that they did not provide any guidance.

These are the same local authorities responsible for setting up and running the local safeguarding children boards (LSCBs) that the government says schools should turn to.

Rachel Krys, co-director of the charity End Violence Against Women, says the findings are “extremely worrying, but not surprising”.

Carron Fox, research and policy officer at Barnardo’s, agrees it is “concerning” that schools across a significant swathe of the country cannot draw on information from their local authority about peer-on-peer abuse.

“I think it’s very concerning because how then does a school deal with it?” she says. “It does seem very concerning that there isn’t that guidance.” Academisation and the creation of free schools has meant that local authorities are no longer solely responsible for supporting schools in handling allegations of peer-on-peer abuse and other safeguarding issues. However, councils still run nearly a third of secondary schools in England. They also have a strategic safeguarding role within their area that includes establishing a LSCB.

In June, a Tes investigation found that reported sex offences in schools have more than tripled in four years. In nine out of 10 cases, the alleged victim in the incident was a young person (bit.ly/SchoolSexCrimes).

A freedom of information request by Barnardo’s in February also found that, between 2013 and 2016, the number of alleged sexual offences reported to police in England and Wales in which both the alleged perpetrator and victim were aged under 18 increased by 78 per cent.

Councillor Richard Watts, chair of the Local Government Association’s children and young people board, insists that local authorities do take their child-protection responsibilities “extremely seriously”.

“When incidents of this nature take place, it is important that schools - regardless of whether they are council-maintained, academies or free schools - work closely with their local authority to provide appropriate protection and support to the children and young people involved,” he says. The patchy local guidance on peer-on-peer abuse may also raise concerns because the existing central government advice to schools on how to deal with the issue has been criticised as insufficient.

In March, Tes reported warnings by MPs and charities that schools were struggling to respond to peer-on-peer abuse because of a “gap” in the official safeguarding guidance. In some cases, this had resulted in schools failing rape victims by putting them back into classrooms with their alleged attackers.

‘Inadequate’ advice

While the Department for Education’s statutory safeguarding guidance, Keeping Children Safe in Education, devotes an entire 11-page section to how schools should handle allegations of abuse made against teachers and other staff, it contains just three paragraphs relating to peer-on-peer abuse.

A report by Parliament’s Women and Equalities Select Committee last September noted that a number of witnesses had described the document’s treatment of peer-on-peer abuse as “inadequate”.

Beyond the dearth of information relating to peer-on-peer abuse, analysis of those councils that do provide guidance shows that schools in different parts of the country are offered conflicting advice. For example, Coventry City Council provides a model policy and procedure for managing allegations against other pupils. The policy states that when an allegation is made, “it may be appropriate to exclude the pupil being complained about for a period of time according to the school’s behaviour policy and procedures”.

However, the guidance provided by Hertfordshire County Council’s safeguarding children board says that, following an alleged case of abuse, “consideration” should be given to the “possible need” to send both the alleged victim and perpetrator home “for a defined period” - an approach that has been criticised.

Krys says parents should not have to put up with a “postcode lottery” in how their child will be treated should the worst happen at school. She also says that the problem goes deeper than simple inconsistency between local authority areas.

“Even within boroughs, schools are doing it differently,” she says. “That’s because there is an absence of direction from the centre.”

End Violence Against Women and other charities believe that the best solution to the patchy and conflicting advice would be for the government to set out comprehensive, detailed guidance that applies to every school in the country.

“The DfE has a massive responsibility in telling schools what to do,” Krys says. “With the best will in the world [schools] aren’t very well equipped to deal with it in a way that is absolutely fair to the alleged perpetrators, but also protects the rights of the victim.”

Michael Simpson, a senior policy officer at children’s charity the NSPCC, says that central government is best placed to act: “[Schools] need that help - they need central government to be offering that guidance, so they can really assess their priorities and make sure they have strong procedures in place.”

The Local Government Association agrees that the DfE has an “opportunity” to clarify the situation. “In light of increasing incidents, there is an opportunity for government to review this guidance and ensure it provides sufficient clarity for both schools and councils,” says Watts.

A DfE spokeswoman says: “We publish statutory guidance for schools and colleges with specific advice on how they should tackle peer-on-peer abuse. It makes clear allegations of this type should never be dismissed and sets out how they should be investigated. Schools and colleges should supplement this by working closely with their LSCB to develop their policy and procedures.

“No child should suffer any kind of abuse and we will continue to work with experts to ensure schools have the information and support they require.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters