New ‘teaching toolkit’ not made to measure

At first glance, it may look like manna from heaven for headteachers: league tables on the effectiveness and cost of myriad educational interventions - reassurance, in other words, about what actually works in Scottish classrooms.

Experts have warned, however, that a “learning and teaching toolkit” that draws on domestic and international evidence remains a long way from being a game-changer, and could even prove damaging if followed too slavishly.

When new interim chief inspector Graeme Logan last month sent out “three key messages” for schools in 2017-18, the last of these - “Close the poverty-related attainment gap” - linked to a Scottish adaptation of a toolkit created by the Sutton Trust and Durham University and fine-tuned by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF).

“There needs to be a clear rationale for the interventions and strategies that you select,” said Mr Logan, and this was “evidence on what works”.

The arrival of the toolkit - which is in its early stages and will factor in more Scottish evidence over time - seems like a significant moment. The need for better evidence is well documented: previous initiatives to raise standards in Scottish schools, such as Schools of Ambition, were criticised for a paucity of evidence on what ultimately worked well.

Louise Hayward, professor of educational assessment and innovation at the University of Glasgow, welcomed Mr Logan’s focus on using evidence to influence teaching practice and said the toolkit was a “good starting point”.

She cautioned, however, that the EEF “relies heavily on particular kinds of evidence, in particular randomised control trials” and added that it would be “a mistake to have too narrow a view of what counts as quality in educational research”.

She recalled the case of former mobile phone giant Nokia, which “paid attention only to big data and missed important messages that led to the collapse of their business”.

Professor Hayward said schools should “use information with care and not look for simplistic solutions to complex problems”; the arts, for example, did not rate highly in the toolkit but other evidence suggested it had “a major and positive impact on learning”.

Even with “all the caveats about any ranking system”, she added, the toolkit did highlight some areas where “there is little point in schools investing time and energy”, such as learning styles.

Former secondary headteacher turned academic Danny Murphy said the toolkit was “a pretty useful resource, as long as people read the small print”, such as this advice: “The most successful approaches on average have had their failures and the least successful their triumphs.” Mr Murphy said that any initiative “might work very well in a specific situation”.

He added: “Of course, the other thorny issue is who sets the criteria for judging whether better learning has taken place. ‘Outdoor’, for example, looks expensive for the benefits in this analysis, but many outdoor education enthusiasts would say it is beneficial in and of itself as an experience, whether or not it resulted in greater engagement in or success in classroom learning - its benefits may only become apparent many years down the road.”

‘Far too broad’

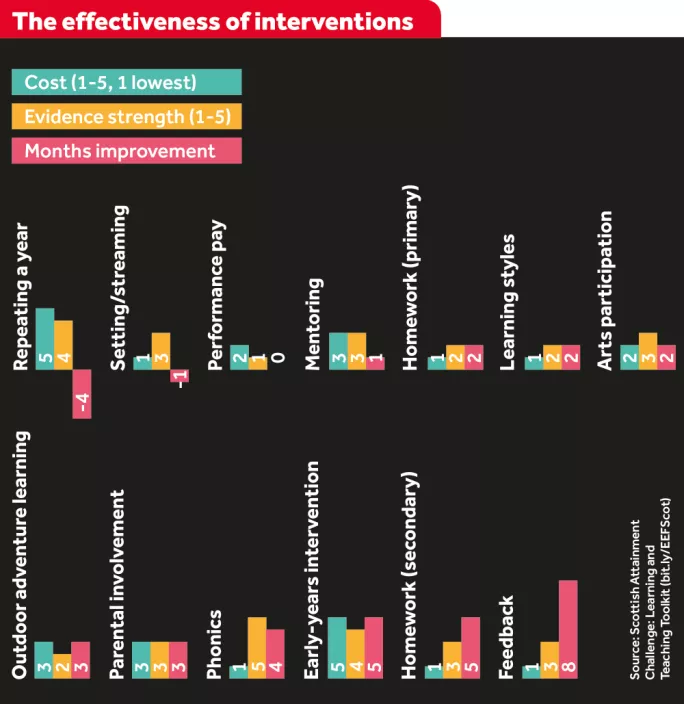

Keith Topping, professor of educational and social research at the University of Dundee, said that some categories in the toolkit were “far too broad to be remotely useful to teachers”, such as “behaviour interventions”, and listing a precise number of months of impact for each category (see graphic, below) was “over-egging the pudding”.

He added: “However, some interesting things do come out of it. The ineffectiveness of setting or streaming, for instance, will be a shock to many secondary school heads.

“Likewise, the low impact of teaching assistants and individualised instruction, not to mention the very modest impact - for very high cost of - reducing class size.”

Walter Humes, honorary professor at the University of Stirling’s Faculty of Social Sciences, said that the league-table approach “as a whole appears crudely quantitative and has a simplistic notion of the scale of change: really effective change takes much longer than a few months”.

He added: “What is largely missing from the toolkit is an emphasis on the qualifications of teachers, as well as their opportunities for professional development and the culture of schools as institutions.”

An Education Scotland spokeswoman said that the toolkit used “relevant examples of Scottish practice” and that work was underway to “develop Scottish-specific evidence in line with Scottish government’s research strategy for education”.

EEF deputy chief executive James Turner said that two-thirds of English schools used the original toolkit, launched in 2011. The EEF was “open about the limitations of the evidence”, he added, which showed what had worked in certain contexts rather than providing a definitive recipe for success.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters