‘Nobody expected all the losers to look the same’

Headteacher Ian Butterfield first thought something was seriously wrong with the accountability system when a neighbouring school received a visit from Ofsted. The secondary had just won a national pupilpremium award, but after the inspection, it was placed immediately into special measures.

Butterfield says he suspected the school had come a cropper because of its low score on Progress 8, the government’s headline secondary accountability measure. Having previously worked as a research scientist before going into teaching, he decided to dig into the data. “I was convinced that there was a problem around Progress 8 not being a true progress measure, but more a reflection of the population,” says Butterfield, who is head of Hindley High School in Wigan.

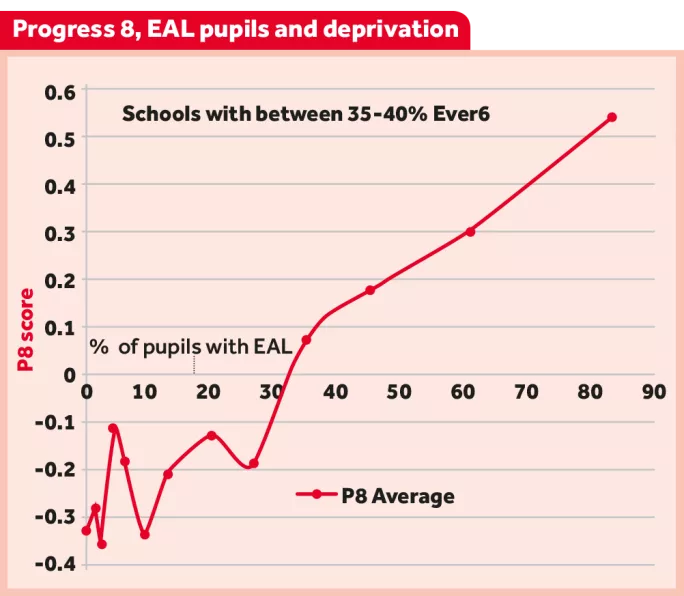

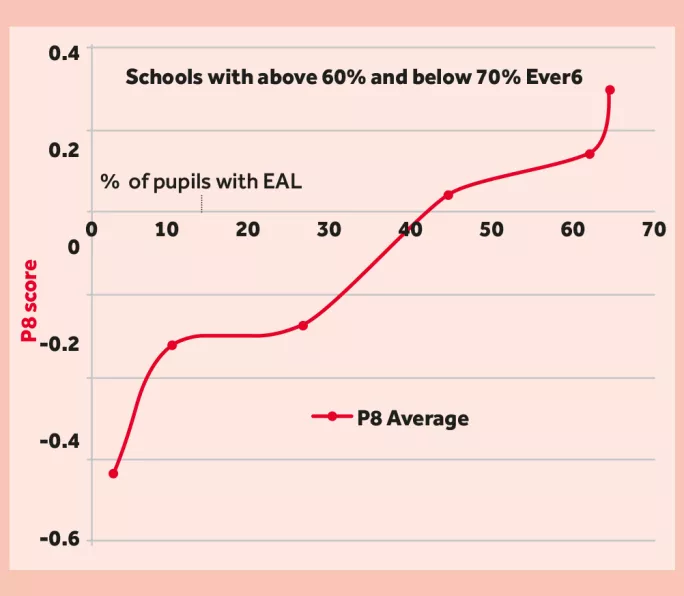

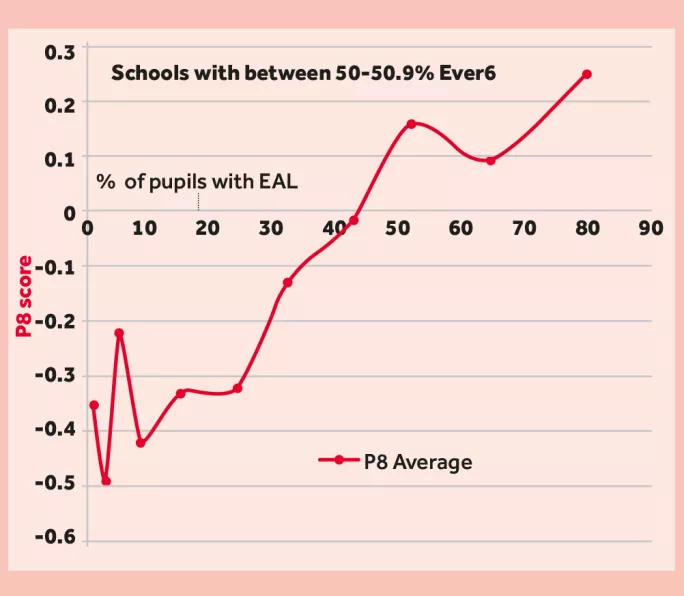

First, he took schools with a similar level of deprivation (as measured by the proportion of pupils who were “Ever 6” - those eligible for free school meals during the preceding six years).

He then analysed how the percentage of children who spoke English as an additional language (EAL) affected the school’s Progress 8 score. To do this, he grouped schools into batches based on the size of their EAL cohort, and then calculated the average Progress 8 score for the batch.

The results shocked him. Each of the graphs showed that as the proportion of EAL pupils increased, so too did the average Progress 8 score. “Progress 8 is primarily a product of pupil deprivation in your school and the EAL population within your school,” Butterfield says. “It’s stark, actually. It’s so clear.”

If a school has 70 per cent or more pupils with EAL, it’s “almost impossible to fail” on Progress 8, Butterfield claims. Conversely, if a school has a high degree of deprivation and less than 5 per cent of its students are EAL, then if it performs in line with similar schools, it’s “going to be a coasting school”, he adds.

For Butterfield, the data shed some light on his local area. “Where I am, I’ve got a school just down the road in special measures; another is “inadequate”. I’m lucky - I’m the best school in the area - and I’m “requires improvement”. But we’re all very similar schools.”

According to Butterfield’s logic, schools in disadvantaged areas with small EAL cohorts (those serving “white working-class communities”, in today’s political parlance) will almost certainly achieve low Progress 8 scores. And when they do, they will attract the attention - and wrath - of the inspectorate.

“Ofsted would argue that [Progress 8] is just one element,” he says. “But there’s a huge correlation between judgements of schools and their Progress 8 score. If you’ve got a positive Progress 8 score, you’re highly unlikely to suffer, and if you’ve got a negative Progress 8 score, you’re going to be under scrutiny.”

Butterfield says the neighbouring school that was placed in special measures actually had a better Progress 8 score compared with the average for other schools with a similar level of deprivation and EAL population.

The findings are troubling for school leaders in white working-class communities. James Eldon, the principal of Manchester Enterprise Academy (MEA) - a school in Wythenshawe, an area of high deprivation in which 90 per cent of pupils are white British - helped Butterfield collate and interpret his data. “

You’re going to get areas of the country, like where I work, where there will be no good schools,” says Eldon. “You could create wastelands of schools that Ofsted will come in and clatter.”

Eldon says he has shared the research with other heads who are leading schools that teach a similar demographic.

He says one of them - a head who had “a particularly difficult, horrible time with Ofsted” - became “very angry and quite emotional” when he saw the data because he realised that his school in fact had a better Progress 8 score than comparable schools.

Underestimating EAL

Ofsted says that school performance data is “only is only the starting point in the inspection process”, while the DfE insists Progress 8 is fair because “schools are now recognised for the progress made by all pupils”.

So why do schools with larger EAL cohorts appear to perform better on Progress 8? The Education Policy Institute thinktank has suggested that it may be down to the fact that the key stage 2 test, used as the baseline for the measure, will underestimate some EAL pupils’ academic attainment because students take it before they have reached fluency in English.

Butterfield is inclined to agree with this view. “If you look at EAL children’s performance, there is a massive positive weighting towards Progress 8 for loads of reasons - one being that their KS2 score is quite low compared with their final KS4 score.”

But he says a full explanation deserves “a research thesis all of its own - there are so many factors and it’s so complex”.

Eldon is well placed to comment on what might be driving the trend. As well as running a predominantly white British school, he has also recently set up a free school, Manchester Enterprise Academy Central - which serves a largely Asian community in south Manchester - where 85 per cent of pupils are EAL.

He says the issue around the improvement of English proficiency can add “significant value in terms of progress”, but thinks other factors are at play.

Eldon says that families with an immigrant background are not necessarily more aspirational than those from white working-class communities, but the former often display “an understanding and an inherent formality, a seriousness to the value of education”.

While he is “wary of stereotyping”, he says that families with an immigrant background are often highly focused on exam outcomes - they don’t just want their child to do well and get a pass, but to do “really well”.

“There are high ambitions and aspirations among the [largely white working-class] families at MEA, but they’re not as confident or perhaps certain about what that looks like in terms of grades, or next steps and pathways,” he says.

No matter what is driving higher Progress 8 scores for EAL students, Butterfield and Eldon say the consequences are clear. They argue that the accountability system is putting people off teaching in certain types of school. “This is causing people to quit their career and quit teaching,” says Butterfield. There’s a “huge disincentive” for school leaders and multi-academy trusts to lead schools in these areas, Eldon adds.

They also think the current situation may damage social cohesion if schools with a diverse, complex demographic are celebrated while schools in white working-class areas are deemed to be failing.

“Whether they are coastal, rural, or urban offshoots, there is an isolationism by definition to many of these populations,” says Eldon. “If you’re then going to have a measure that says ‘and actually you’re not just isolated, you’re not very good compared with other types of school’, you’re compounding that.”

Eldon says that for those striving to get good results for students in deprived areas, “there has to be a sense of hope and a sense that it’s doable”. He adds: “Any progress system based like this will have to have losers in it. It’s just, I guess, nobody expected all the losers to look the same.”

Progress 8, EAL pupils and deprivations

Each graph below relates to all of the schools in England with a certain level of deprivation, as measured by the proportion of students who are classed as “Ever 6” (which includes any pupil who has been eligible for free school meals during the previous six years).

Each point on the graph shows the average Progress 8 score of a cohort of 50 schools that have been grouped together because they have a similar percentage of students who speak English as an additional language. The graphs show that as the size of the EAL cohort increases, so too does the average Progress 8 score.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters