Reaching the peak? Mystery surrounds new top grade

Just how many students will get a clean sweep of top grades in the new, harder GCSEs?

The world of education was left scratching its collective head last week after a top Department for Education adviser suggested that the answer would be just two.

The remark from Tim Leunig, the DfE’s chief analyst and chief scientific adviser - just weeks before the start of exams - shocked many teachers still grappling with the new GCSEs and grading scale.

The 9-to-1 grading scale was introduced to better recognise the achievements of highattaining pupils. Under the new system, a grade 9 - the new top grade - will be harder to achieve than a current A*.

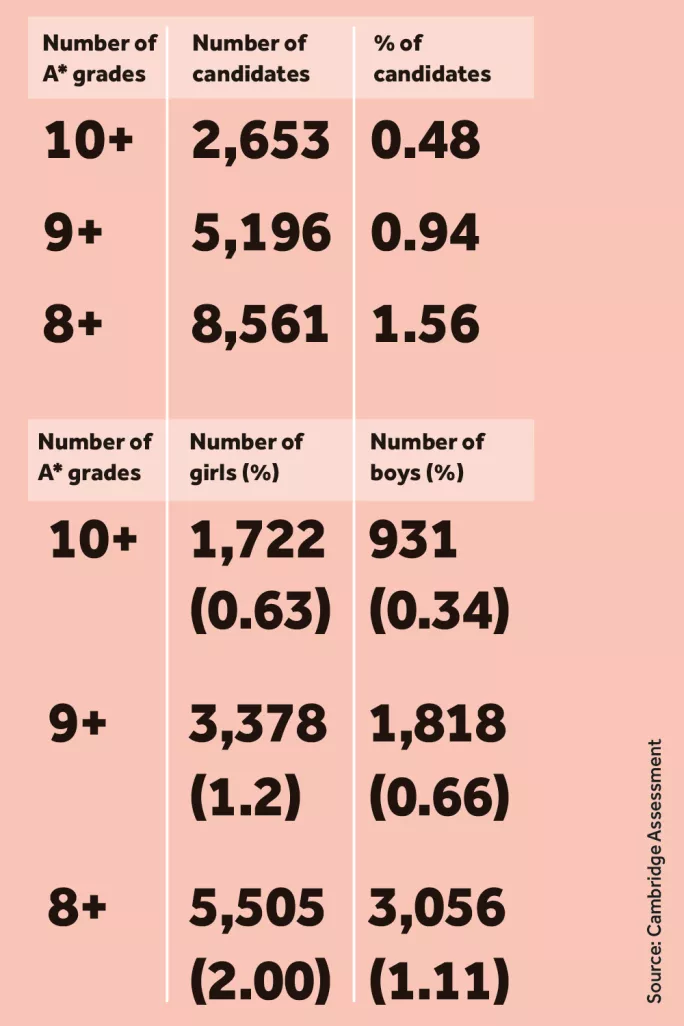

Thousands of candidates currently achieve straight A*s in their GCSEs (see data box, right), but will the nine-point system make it almost impossible for high-achieving pupils to secure top grades in all of their GCSEs?

Not according to one of England’s major exam boards. Cambridge Assessment predicts that hundreds of pupils will gain all grade 9s once all the subjects have moved to the new numerical scale.

Grade 9 ‘not much harder than A’

Tom Benton, a Cambridge Assessment researcher, says that grade 9 is “not that much harder than A*”.

New GCSEs graded 9 to 1 are being introduced over a four-year period - with the first exams in English literature, English language and maths being sat this summer.

Benton says: “In the long-term, when everything has gone over to the new scale, I would expect hundreds of people to get straight grade 9s.”

For each individual subject, he predicts that there will be “thousands” of grade 9s. “If you do well in maths, then you are more likely to do well in the other subjects,” he adds.

Benton elaborates: “If you get a grade 9 in one, then you are more likely to get it in the others. When you take that all in, then you get a number a lot higher than two.”

If you get a grade 9 in one, then you are more likely to get it in the others. When you take that all in, then you get a number a lot higher than two

Exams regulator Ofqual has said that, across all subjects, about 20 per cent of all grades at 7 or above - the equivalent of a current A and above - will be awarded a grade 9.

What has become apparent amid conflicting messages about the 9-to-1 system is that many teachers, students and parents remain in the dark about what the grades will look like and count for in the long term - despite the fact that the first set of new GCSEs in English and maths are being sat this summer.

Last week, education secretary Justine Greening tried to provide some clarity about the changes when she announced that grade 5 - the equivalent of a high C or low B - would no longer be classed as a “good pass”, but would instead be a “strong pass” and that a grade 4 would be a “standard pass”.

It is a clear climb-down from the government, which announced in 2015 that a “good pass” at GCSE would be a grade 5 - which would be harder to achieve than a current C - to bring it in line with the average performance of pupils in countries such as Finland, Canada, the Netherlands and Switzerland.

Former education secretary Michael Gove had written to Ofqual in 2013 about plans for the new GCSEs. He said: “At the level of what is widely considered to be a pass (currently indicated by a grade C), there must be an increase in demand, to reflect that of high-performing jurisdictions.”

In 2014, Ofqual admitted that trying to ensure that England’s reformed GCSEs matched the world’s most “rigorous” standards had been “challenging”.

Despite admitting its inability to directly compare the country’s system with other education systems, Ofqual said that the standard for a grade 5 would be “internationally benchmarked”.

Now, Greening has said that a grade 4 - the equivalent of a middle or low C - is enough for a pupil to avoid compulsory post-16 resits in English and maths, as well as to be admitted to college - and the proportion of pupils achieving a grade 4 will also be included in schoolperformance tables.

Ongoing confusion

Malcolm Trobe, interim general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says: “What is clear is [the government] did not want to see a large number of young people labelled, potentially by the media, as not being successful.”

However, confusion remains in the sector as the more demanding grade 5 - a “strong pass” - is still the government’s aspiration and the benchmark for schools in performance measures like the English Baccalaureate, despite the softened pass announced for pupils (see box, below).

Some teachers are still struggling to identify which standard they are working to and which grades to predict under the nine-point scale, which does not directly match up with the old alphabetical scale.

“It is confusing,” says Sarah Jennings, an English teacher at Lady Lumley’s School in Pickering, Yorkshire. “We are just constantly trying to push our students into achieving the best for them, based on where we think the grades will fall. We would say this would have been an ‘old money’ C, but where that falls on the new course, we don’t know.”

Ofqual has warned schools against trying to predict the grade-boundary marks for the new GCSEs, saying it would only be a “best guess”. So for many teachers, results day will be their first sight of what the new grades look like.

There is also a chance that some schools will achieve lower grades than expected under the new qualifications. In a letter to heads last week, Ofqual boss Sally Collier said changes were “likely to mean individual schools and colleges will see more variation” compared with last year.

But she tried to reassure schools that national results would “remain stable”, as statistics will be used to ensure that the cohort taking the new qualifications will not be disadvantaged compared with previous years.

This means that broadly the same proportion of pupils will be given grades 1, 4 and 7 and above in any subject as would have received grades G, C and A and above.

But Ofqual’s statistical approach to grading - known as “comparable outcomes”- will not provide a comfort to all heads. Trobe believes that the controversial approach has a limiting effect on the proportion of students who can achieve both the government’s “standard” and “strong” passes. “There is an expectation on schools that youngsters will improve and more of them will do better,” he says. “But the use of comparable outcomes means that can’t happen.”

An Ofqual spokesperson says: “We’re aware of recent comments and discussion around the number of learners who might, in the future, receive grade 9 results in all of their GCSE exams. We have not done any modelling regarding these numbers and make no prediction of figures like these in advance of a future awarding process. Neither did we previously make these kinds of calculations for the number of A* awards at GCSE.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters