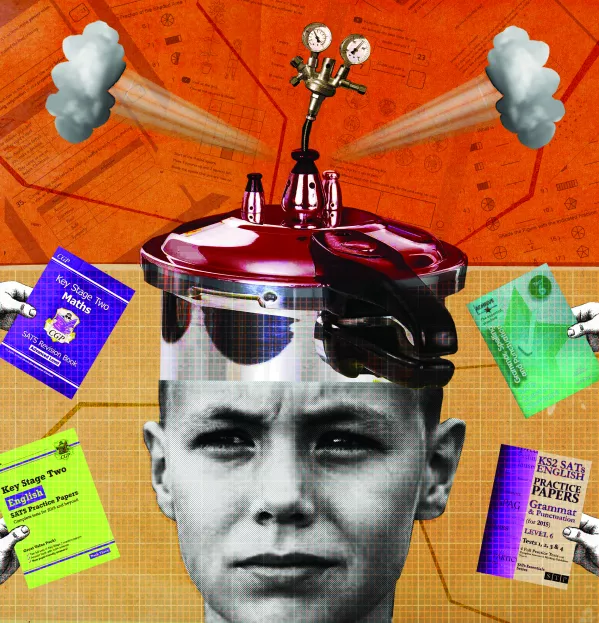

Sats are far more than ‘just another test’

Sats week is upon us again. Each year, wedged between the London marathon and the FA cup final, comes the most pressurised spell of the primary year - when England’s 10- and 11-year-olds are challenged to get over the line in tests that will see their schools ranked against each other.

Schools put up “quiet please” notices on the Year 6 classroom doors, teaching assistants are redeployed to invigilate and EduTwitter is filled with survivor in-jokes about past Sats questions. But not everyone copes well with the impending challenge.

“Sats and the regime of extreme-pressure testing are giving young children nightmares and leaving them in floods of tears,” Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn told delegates at the NEU teaching union’s national conference last month, saying that, should Labour come to power, the Sats would end.

Education secretary Damian Hinds retorted that it was quite possible for Sats to go by without children feeling stress, comparing them to dental check-ups. It’s an interesting analogy as, for many children, a visit to the dentist is likely to bring to mind apprehension and fear. For some pupils, the same could probably be said about Sats.

The tests were introduced in the early 1990s as part of the government’s accountability regime to check on how schools were performing and, by extension, its own education policies. They ought to have no real bearing on the lives of pupils, and yet some are having sleepless nights.

Like his boss, schools minister Nick Gibb is convinced that it doesn’t it have to be this way. “The heads I meet, who are running very good primary schools, say: ‘We would not dream of putting pressure on our young people,’” he says. “Sometimes, pupils don’t even realise they are taking tests.”

But if that’s true, why is the pressure on in other schools? Is there just too much to lose in a high-stakes accountability system to carry on with business as usual, simply slotting in the six test papers around lessons, PE and lunchtime? Or is there, even in the most confidently led schools, something about the test process itself that pupils cannot help but pick up on?

On Monday, around 600,000 children aged 10 and 11 will be sitting at their desks ready to take the first Sats test - a 20-word spelling test and 50 questions on punctuation and grammar. Clare Sealy, headteacher of St Matthias CE primary in East London, agrees with Hinds that school leaders can reduce stress, but points out that there is a limit to quite how oblivious children can be kept to the importance of the test.

“It is a formal exam,” she says. “The children know it. They are sitting at a desk by themselves, they are not allowed to talk and have to work solidly for 45 minutes.”

But Sealy hopes that, after several mock Sats and - in some years - Easter revision classes, the apprehension has transformed into something more positive.

“For the children, there is a vibe about them coming up,” she says. “They are a bit nervous but it’s a bit like running a marathon - something they have worked for and want to do their best in.” She is also careful about the language she uses, avoiding “pass” and “fail”, and motivating children who are not at the expected standard by explaining that they are not at it “yet”.

A similar approach of reducing stress by reframing exams as opportunities to demonstrate what you know, rather than traps aimed at revealing weak spots, is taken by Chris Wilkins, executive headteacher of the St Ninian Catholic Federation, Carlisle. He has argued in Tes that Sats shouldn’t stress pupils out. When that does happen, it is because teachers are passing their own stress on - which has probably also been passed on to them by their headteachers.

“We make sure any pressure is off teachers; we ensure that leadership sucks up pressure and teachers don’t feel it,” he says.

“We establish that Sats in Year 6 are the outcome of the past four years of work - it is a shared outcome.”

And for pupils, they have lots of “low-stake” testing in the run-up so that they understand what they will be doing and that it is a chance to show what they can do. “In life, some people enjoy [job] interviews, they see them as a positive experience. It is about instilling that mentality,” he explains.

Striking the balance

Both Sealy and Wilkins eschew the idea that no test preparation would reduce test stress. Spending time running through past papers is seen as a way of helping to ease fears about what will happen on the day - after all, practising in advance is the approach that adults use to prepare for the most stressful situations. As retired astronaut Chris Hadfield puts it: “No astronaut launches into space with their fingers crossed.”

But how do headteachers strike the balance between ensuring that pupils have enough preparation to reduce stress without tipping over into so much preparation that pupils get the anxiety-provoking message that these are going to be really, really tough exams?

At Cavendish Community Primary in West Didsbury, Manchester, preparation begins after the autumn half term in Year 6. “From October/November, we run booster classes for all children in English and maths,” headteacher Janet Marland says. “We rejig the timetable and cut down on foundation subjects. We reduce the amount of time during the first two terms on subjects like drama and music, which we then do after Sats, but we still do history, geography and science. So, we probably end up doing an extra three hours a week on English and maths.”

The booster classes also involve splitting the 60-strong year group into smaller groups - with the deputy head teaching to enable this. As well as the rejigged timetable, there is one-to-one tuition after school for some children and an optional Easter revision class, which this year included a trip to engineering firm Siemens. A few past papers are done over the year to familiarise children with the test itself. Marland says she wants her pupils to feel confident when they come to take the tests and believes this is the level of preparation needed.

Narrowing the curriculum prior to Sats is common. In a Tes/NEU survey last year, 46 per cent of teachers said their schools started running KS2 Sats preparation sessions in the autumn term and 74 per cent said that other parts of the Year 6 curriculum got squeezed out “a lot” in preparation for Sats.

But are these schools really thinking about pupils or is it, in fact, about their own accountability?

Schools that don’t do well enough and fall below the floor standards can be forcibly academised or moved to another trust. The headteacher could lose their job. Teachers’ actions will be closely scrutinised.

And while the government is removing Sats as a trigger for intervention and relying instead on Ofsted judgements, it wants performance data to “remain a key feature of the system”.

This accountability system has been put in place because the government thinks that ensuring pupils leave primary with sufficient proficiency in literacy and numeracy is vital - the Sats are a lever, not just a neutral check-up. They are designed specifically to ensure that primaries pay special attention to English and maths.

‘A flying start’

Primary headteachers also need to consider the fact that their pupils will be going on to, in most cases, much larger secondaries, where they will be moving between several teachers each week and will need to be more self-sufficient. So, the better prepared they are in these essential building blocks of their education, the better they will do.

This is a key issue for Marland’s school, where around 30 per cent of pupils have been eligible for free school meals in the past six years and a high proportion have English as an additional language. “Rather than link [the preparation in Year 6] to the Sats, we say that this is about making sure that when you leave us, you are confident about your next steps, that you are starting secondary school with the skills, knowledge, understanding and confidence you need for a flying start,” the headteacher says.

She rejects the argument that what she is doing is about the school rather than the pupils. “If we were really focused on being at the top of the league tables, we’d be constraining the curriculum from Year 5 and I know schools that do that. We have no constraining earlier in school. We have two whole years of music tuition, so all pupils leave reading music - the breadth of our curriculum is strong.”

And if the curriculum does narrow in the Sats run-up, almost all schools ensure they have a flurry of post-tests leavers’ events: residential trips, plays, PSHE sessions, music concerts, sports days and visits to secondary schools, alongside the more academic lessons.

Headteachers know their pupils will inevitably be spending more time than usual in June and July on PE, music and drama. So, reducing those subjects earlier on can provide more balance over the year as a whole.

Broad and balanced

But other schools argue that the tests do not necessarily reflect the learning that children will need to do well in secondary. Instead, they believe keeping a broad curriculum for as long as possible in Year 6 will help pupils more. “There are some schools that, the moment they start in September, they are prepping,” Simon Smith, headteacher of East Whitby Academy, in Whitby, North Yorkshire, says. “I don’t believe in that. I believe if we keep teaching a broad and balanced curriculum, the children will be in a better place to do well in these tests anyway.”

He starts familiarising children with the test format about two weeks before Easter, to help reduce stress. But he is not convinced that the tests align closely enough with the curriculum to justify doing more than that.

“Our curriculum, which is broad and balanced, probably does have a lot more writing and books than some schools, because that is what our children need,” he says. Smith adds that, as he believes the reading test is more of a “test of general knowledge” than of reading, sticking to his school’s curriculum gives pupils a better chance of reaching the expected standard than narrowing their focus.

He admits he does feel pressure - especially when the school slipped to 44 per cent of pupils reaching the expected standard in 2017, compared with a national average of 61 per cent (they have improved since this “blip” year). He feels able to deflect this pressure from pupils. But, while high-stakes accountability may quickly identify struggling schools, Smith points out that it also deters some teachers and headteachers from taking them on. And it isn’t just struggling schools where the pressure is felt.

Sats don’t just give a sense of who is at the bottom of the table, but who is at the top. Indeed, one reason that the results are public is to enable parental choice in school admissions - and research has shown that middle-class parents are far more likely to draw on such information than working-class parents.

In fact, it is not always schools that put the pressure on. Parents may be the ones buying revision guides and urging their children to take the tests seriously - 30 per cent of primary-school pupils whose mother had a postgraduate degree had private tuition, compared with 19 per cent of those whose mother had no qualifications, the Nuffield Foundation reported in 2015.

Even where parents and schools agree that pupils should be protected from pressure, the politicians’ insistence that Sats are not a measure of the child but the school does not take into account how that message comes across to children themselves.

Kay*, whose daughter attended a West Sussex primary school, says she was not keen on her daughter taking the Sats last year, but she wanted to challenge herself and do them. “The school would say there was no pressure on the child,” says Kay. “But children want to please their teachers, so there is pressure regardless of whether or not the school thinks there is, just by the whole way it’s focused on English and maths in Year 6. I have no objection to children sitting tests but I object to such high stakes.

“They can’t help but be pressured because it means so much to the school,” she says. “The headteacher’s job depends on the Sats, the teachers may not get pay rises - and that can’t be the children’s responsibility.”

When Sats week starts, the bureaucracy, formality and detailed rules and regulations that surround the tests mean it would be virtually impossible for a child not to register their importance.

One pupil’s supportive revision class is another person’s hour of repeated failure. But everyone knows that the Sats are happening. And everyone knows they are far more than “just a check-up”.

Helen Ward is a reporter at Tes

*Name has been changed

This article originally appeared in the 10 May 2019 issue under the headline “Stress testing”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters