‘Schools don’t need cash to close the attainment gap’

It sounds rather like the promised land - but could there be strategies that would allow schools and local authorities to tackle Scotland’s notorious attainment gap without spending an extra penny?

The idea that there could be such miracle cures for one of Scottish education’s biggest problems is just one eye-catching message from a project designed to get teachers across the country working more closely with colleagues from other schools.

The final evaluation of the School Improvement Partnership Programme (Sipp) has found that teachers can significantly improve the prospects of children from poor backgrounds with little - if any - extra funding (see the evaluation here).

Sipp, which also helps teachers to apply the latest education research in the classroom, has proved a hit with schools amid shrinking local authority budgets.

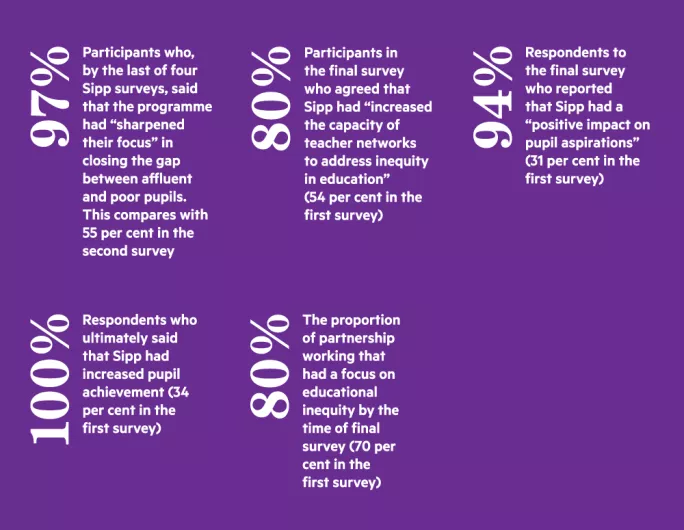

Teachers report that the project, designed to spark “innovative collaborative working” with “modest” funding, has had a dramatic impact. In an early survey that was carried out soon after Sipp was launched in 2013, around a third of respondents said that it had increased “pupil achievement” - but by the final survey that had risen to 100 per cent.

And while some 31 per cent initially said that it was raising pupil aspirations, that has now jumped to 94 per cent.

For example, a joint project by Clydeview Academy, in Inverclyde, and Dunoon Grammar, in Argyll and Bute, had increased the number of target pupils taking National 4s, while there were signs of the East Lothian-Midlothian partnership reducing pupil exclusions.

Meanwhile, Sipp teachers’ understanding of disadvantaged pupils had “substantially increased”, the report suggests.

Limited funds

These successes were achieved despite no funding being available for the third year of the project, which involved a total of eight partnerships, after £690,000 was spent on the first two years.

“The rationale for providing limited funding was to encourage partnerships to explore approaches that were not reliant on funding and, therefore, were more resilient to economic uncertainty and flux,” said the report from the University of Glasgow and Education Scotland, which jointly ran the Sipp project.

But the authors go even further, saying that it is “arguable” that defining features of successful partnerships across schools and local authorities “do not necessarily require additional funding”. These features included a “risk-taking culture” and “high levels of autonomy” for teachers.

Professor Stephen McKinney, of the University of Glasgow - a member of the Sipp team - said that “some of the schools have done brilliant work”.

‘Partnerships explored approaches that were not reliant on funding’

The programme had demonstrated a potentially lasting impact, Professor McKinney added, if schools are encouraged to find ways of tackling the attainment gap that suit their local circumstances. Joint working with other schools and councils - along with support from universities in accessing academic research - could also help projects to thrive even after funding stops.

Jim Thewliss, general secretary of School Leaders Scotland, said: “While it is heartening to find teacher professionalism overcoming financial and other constraints, I would be loath to turn adversity into a virtue.”

But he added that projects like Sipp, which provide some initial funding then limited ongoing support, “can be a powerful lever of change when judiciously targeted”.

John Stodter, general secretary of the ADES education directors’ body, said that the Sipp findings were “very positive” and that his organisation had fostered similar partnerships across schools and local authorities.

‘Challenges ahead’

But Mr Stodter cautioned that the number of pupils involved in Sipp was small and that there was “as yet no hard evidence on the direct impact of the partnerships on attainment”. He added that Sipp-style projects could be difficult to maintain in a time of “significant budget reductions”.

The Sipp report comes with a number of qualifications. The programme’s collaborative element - which previous research in England had shown overcoming a resistance to experimentation in more isolated schools - had “drifted” in three partnerships after funding ended.

Some parts of the scheme, such as the Glasgow side of a Glasgow-Fife partnership, were “ambitious in scale and arguably faced particular challenges in establishing coherence”. And all of the partnerships anticipated difficulties in sustaining their Sipp activities, with staffing levels the most common challenge.

Lessons from Sipp are already influencing efforts to eliminate Scotland’s attainment gap - the issue that first minister Nicola Sturgeon has said her government should be judged on above all else.

A spokeswoman for Education Scotland said: “The valuable learning that was gained from Sipp, highlighted in the University of Glasgow’s evaluation report, is now directly influencing the broader work of the Scottish Attainment Challenge, while also continuing to inform the improvement work of the schools and authorities which were directly involved in the programme.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters