‘Smile to help the youngest widen their vocabulary’

Teachers who act more like parents by using emotive words could boost children’s grasp of complex vocabulary, research suggests.

Researchers claim that schools could also help pupils to gain a rapid mastery of abstract words in the first few years of primary by smiling a lot and talking about events that make children feel happy, such as birthdays.

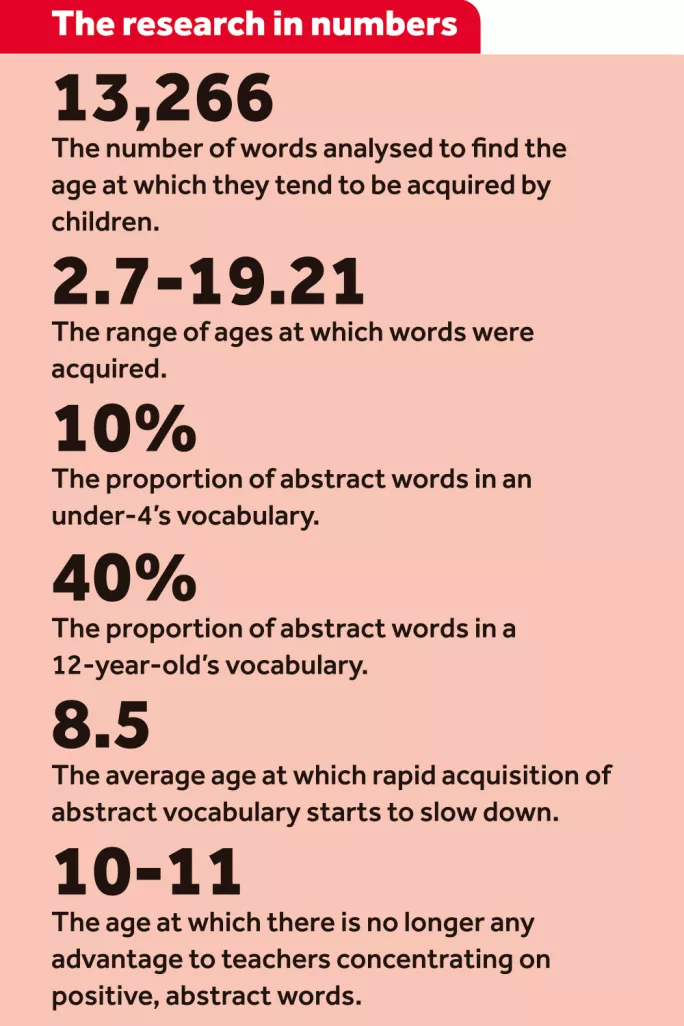

Understanding words such as “cup”, “ball” or “dad” is relatively easy for children, academics say, because these are things they can see, touch and manipulate. Before the age of 4, such “concrete” words make up the vast majority of a child’s vocabulary.

The key to learning trickier, abstract vocabulary, they explain, can often be found in interactions between parents - or other caregivers - and their children.

When children are around age 4 or 5, for example, parents tend to emphasise more emotional, abstract words such as “good”, “naughty”, “pretty” and “cute”.

Lead researcher Gabriella Vigliocco, professor of psychology of language at University College London (UCL), said: “The caregiver will express emotions while saying these words, for example smiling…and when they pick up the smile, children…will feel some emotion themselves as well.”

‘There’s a bias towards positive words being learned before negative and neutral words’

This makes it easier for them to understand that such words refer to something internal rather than “objects out there in the world”, Professor Vigliocco said.

Exaggerated use of emotional words, especially those with positive connotations, is thought to help children as they prepare to enter a period of their life, from age 6 to 9, when - the research shows - they rapidly accumulate complex words.

By the age of 9, about 40 per cent of their vocabulary will be abstract, perhaps including difficult concepts such as “goodness”, “heaven”, “dream”, “trouble”, “tragedy” and “shame”.

Professor Vigliocco said previous research on early vocabulary acquisition had focused on words relating to objects, but this was the first study looking in such detail at abstract words.

She argued that these findings had the potential to help teachers. For example, when introducing a new topic, she said, “the teacher could put up front more abstract words that have emotional connotations”.

Happy occasions

Teachers could also try introducing vocabulary in a “more smiling and emotionally connected way”, said Professor Vigliocco, perhaps by focusing on an incident or event filled with emotion, such as a birthday or someone being hurt - but mostly positive scenarios.

“What we do see very clearly is that there’s a bias towards positive words being learned before negative and neutral words,” she said. “It’s just part of our society and culture that we want to have beautiful, nice things around our children - we want to protect them from negativity.”

She warned, however, that educators should take care not to overload children when they are younger and “not quite ready” for complex abstract words.

The research was based on 60 “typically developing” children aged 6-12 from mainstream classrooms in south-east England.

‘Good teachers instinctively add emotional connection to everything they teach’

Children were asked to press a green button if a word they knew came up on a screen, or a red button for a “funny made-up word”. They were then shown - one after the other, in quick succession and in random order - words from a pool of 24 abstract words, 24 concrete words and 48 non-words.

Scotland’s teacher of the year in 2015, Anne Hutchison, of Carmyle Primary School in Glasgow, said that she could see how the approaches recommended by the UCL research might help her primary pupils.

“In the age of social media and computers, nothing really beats a teacher to help children learn, and I think that good teachers instinctively add emotional connection to everything they teach, not just abstract vocabulary,” she said.

“This definitely helps children to progress because they want to do well when they are encouraged with a smile and feel secure in their learning.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters