‘Staff are seen as a cost, not as professional stakeholders’

After losing the Conservative Party’s majority in the House of Commons at last year’s general election, Theresa May signalled an end to austerity.

The chancellor, Philip Hammond, then indicated a loosening of the purse strings with his 2017 Autumn Budget.

Now, the government has announced that NHS staff will get a pay rise of 6.2 per cent over the next three years. This will be funded by the government and will cost the treasury £4.2 billion - protecting hospitals’ already stretched bottom lines.

There has been no such overture yet to teaching staff in FE, where pay has remained stubbornly static for almost a decade, with colleges insisting their tight budgets simply do not allow for a significant increase.

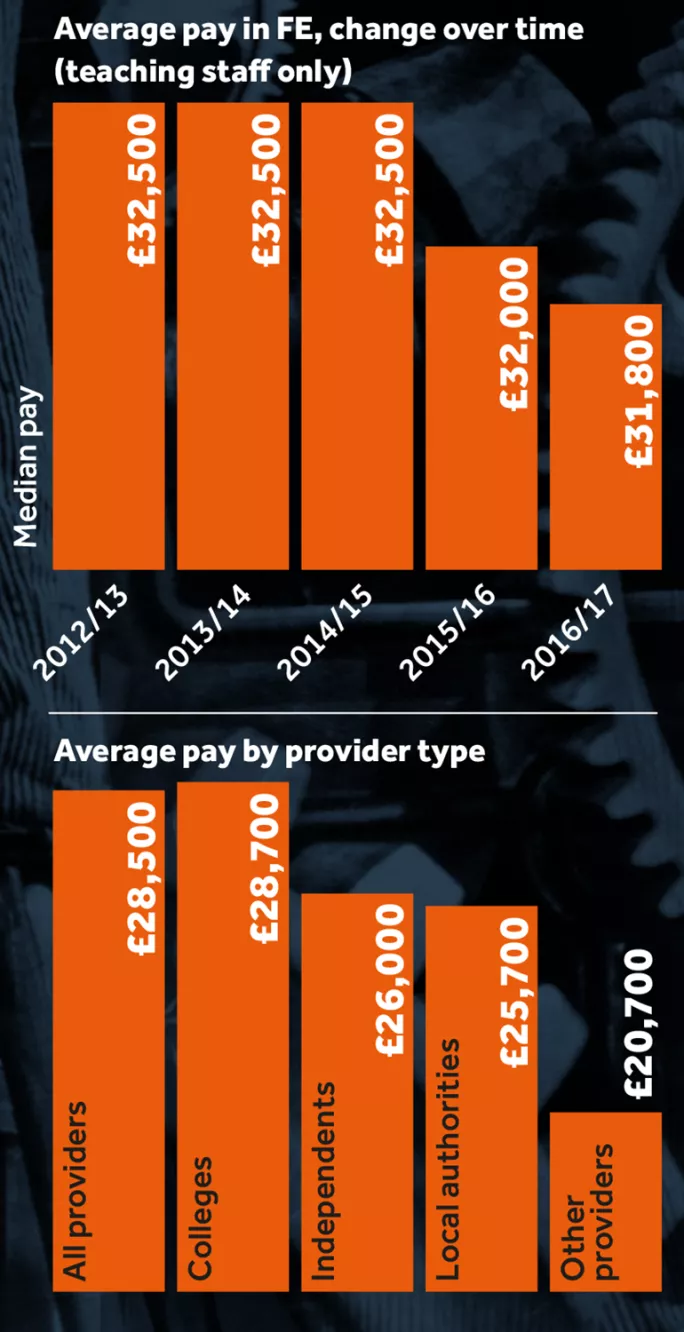

This is highlighted by the latest figures from the Education and Training Foundation’s further education workforce data for England. Published today - and revealed exclusively by Tes - the report is based on Staff Individualised Record (SIR) data from 111 colleges, almost half of the total in England, and a number of other providers.

It shows that over the past five years, the median pay packet for teaching staff has fallen by 2.2 per cent to £31,800.

With the cost of living rising faster than wages, this masks an even steeper decline. According to the University and College Union, staff are now 24.7 per cent worse off today compared with 2009 prices - even in colleges that have agreed to recommended pay increases since 2009.

This week, UCU members at a number of colleges walked out in a dispute over pay and working conditions. This follows strike action at 14 colleges last month.

The union’s general secretary Sally Hunt says that the systematic holding down of pay is the root cause of the two sets of strikes in the space of a month.

“While there is finally a consensus that pay is a real problem, staff continue to see their living standards decline year on year,” she adds.

What colleges want

David Hughes, chief executive of the Association of Colleges, says that a major part of the case for better funding for colleges is to allow the reward packages to be more competitive.

“Every college wants to attract and retain the best people,” he says, “but it is clear that cuts to FE funding over the last decade have disproportionately hit colleges - impacting directly on their ability to reward staff.

“We will work closely with organisations to campaign for fair funding for colleges and address the under investment which the sector has faced for too long.”

The ETF’s report also shows there has been a marked increase in the number of zero-hours contracts across the FE workforce.

In the past year, there has been a 2 per cent increase, meaning that staff on zero-hours contracts now make up one in 20 members of the FE workforce.

College staff are more than 10 times more likely to be employed on a zero-hours contract than at an independent provider, according to the ETF’s data.

The report states that a fuller picture will be possible in coming years as more data becomes available, as this is only the second report that has monitored the level of zero-hour contracts.

Norman Crowther, the national official for post-16 education at the NEU teaching union, says that the rise in zero-hours contracts is a disappointment.

“We have been arguing for some time that casualisation not only demotes the status of teachers and staff in the sector but also adds to the flexibility colleges have over staff costs,” he adds. “Staff are seen as a cost and not as professional stakeholders in the sector.”

Time for change

Next month, at the annual conference of Association of Teachers and Lecturers section of the NEU, the FE lead member group will call for a national contract, a “robust and credible pay mechanism” and a professionalised workforce.

“The recruitment problems in the sector, the low morale and the growing casualisation all point to a race to the bottom rather than to the top,” Crowther adds.

Hunt agrees, arguing that where employees want flexibility, colleges should provide it, but warns: “They should not impose contracts that give staff no guaranteed income or hours. We urgently need better data on the levels of people employed on casual contracts if we are to properly address the issue in our colleges.”

Hughes stresses that there is a need for a flexible and dynamic workforce to meet the challenges of the skills agenda, adding: “FE reflects the changing world of employment generally but prides itself on being a good employer.”

A Department for Education spokesperson says that teachers’ pay is a matter for individual colleges to decide upon.

“The department has committed £19 million to support teaching in further education, including over £4 million in bursaries that are worth up to £25,000 per person.”

Pay differentials

According to the Office of National Statistics, FE lecturers are still paid significantly less than their teaching colleagues elsewhere in the education sector. University lecturers earn on average 34.6 per cent more than those in FE, secondary school teachers earn 8.3 per cent more and primary and nursery teachers earn 0.7 per cent more.

Charlynne Pullen, head of data and evaluation at the Education and Training Foundation, says: “As has been the case for a number of years, and as is highlighted in the report, teachers in FE are paid less than secondary school teachers, on average.”

Pay is not uniform across the UK. Because education is a devolved policy, pay scales are different across the England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

A qualified lecturer, who is not involved in advanced training, can earn up to £36,524 in England, for example. However, lecturers at colleges in Wales can earn up to £38,246, while in Northern Ireland a typical lecturer can earn up to £32,778.

Meanwhile, lecturers in Scottish colleges are all to be moved onto a new pay scale towards a salary of over £40,000, after a pay deal was agreed in 2016.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters