Supply and demands

You’re on supply at a school you’ve never worked at before, and first up it’s Year 8.

They’re cheeky and take time to settle: “Are you a proper teacher?” “Have you got kids?” “Are you gay?” “Do you watch Family Guy?”

By contrast, in period two you feel as if you’re invisible in front of Year 11 bottom set English. You learn names, you smile, you chat and you gently start to encourage them to get their books out, to sit on chairs and not desks, and to remove their coats, caps and headphones.

They ignore your instructions and start moving desks and chairs so they can sit closer together, while a boy blatantly opens a can of energy drink in front of you. You tell him to put it away but he becomes confrontational and swears at you.

Right on cue, the head of year enters and suddenly the pupils turn into angels, taking off coats and opening books. You feel as if you’re in the presence of a superhuman.

At break, in the staffroom, the head of year ignores you. You try to engage in chat with other teachers, but they’re cold. You wonder if you’re sitting in someone’s chair.

Many would say that supply teachers have always been up against it. While the job allows greater freedom and generally less workload, it can be a lonely life, and traditionally one in which you get less respect than other teachers.

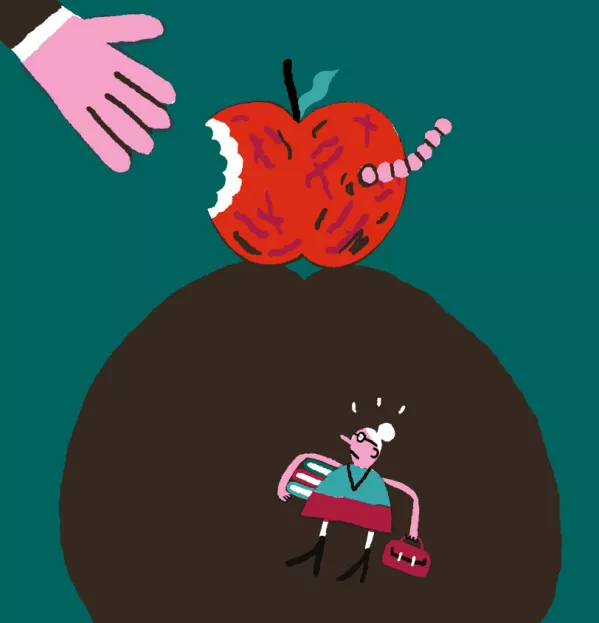

New research has shed light on just how little attention is devoted to giving these essential staff even the most basic tools that they need to do their jobs. Many supply teachers are simply given a map, a timetable and a name badge before being sent off to teach the most unruly classes in the school - without even a sniff of the school’s behaviour policy or being forewarned about pupils with behavioural issues, or those with special educational needs.

That could be because the school hasn’t given them the information, or because they haven’t had time to read it - they might have only got the job an hour ago.

And a recent survey by the NASUWT teaching union highlighted how supply teachers can be up against it from another angle: the agency that employs them.

In some cases, how they are employed amounts to “exploitation”, says the union, which found that out of the £1.1 billion spent by schools on supply teachers last year just 31 per cent actually went to the teachers.

“The agencies take money off you for every little thing,” says Mary, a former head of department who began supply teaching 18 months ago. “They say they won’t register you unless you do their training courses, and guess what? You have to pay for them as well. And a course can cost up to £200.

“It’s just another way to make money, but you don’t want to make a big fuss because you need the work.”

Mary, who earns up to £160 a day (when the agencies offer her work), says she is forced to pay 3 per cent of her daily rate to an umbrella company that handles payroll (which can cost up to £100 a month, if she works every day).

She says that the bargaining power of supply teachers has been diminished by ex-police officers and soldiers who are employed by the agencies as cover supervisors, and who are happy to work for lower rates because they are already on a pension.

“They might be good at discipline but they’re not trained teachers,” Mary explains. “And we’re going to see the effects in a few years’ time when kids are not passing their exams.

“I’ve seen NQTs being paid as little as £40 or £50 a day, while the agencies are making a fortune. They’re making a minimum of £50 a day out of each of us.

“There are two agencies setting up every month where I live, because they know how much money they can make. Last year, in one agency I know of, there were 12 people, but now it has taken over two floors in a large building and it has all this fancy furniture.”

‘The Wild West’

Some are wondering whether supply teaching is worth continuing at all. Mary, who has almost 20 years’ experience and was on £45,000 in her head of department role, says she reached the lowest point when she turned down a £60-a-day job as a cover supervisor, which was 25 miles away from her home. Instead, she took a £7 per hour factory job, which was closer.

“You grit your teeth and you get on with it, and you’re like anyone else in the factory. You work hard or you go under. We’ve all got mortgages and bills to pay,” she says.

The NASUWT describes a “murky world” akin to “the Wild West”, in which supply agencies are operating without enough regulations.

It says, for instance, that there is a common practice of tying up the best teachers in bogus bookings to keep them free for the next day and to prevent them from being booked by rival agencies.

Supply teachers also report deductions being made from their daily rate when they are given a free period.

Last year, Tes revealed that agencies were sending teachers on unpaid trial days.

And all the while the agencies are making “huge profits” and keeping teachers’ rates down, says the NASUWT.

It states that schools are paying around £200 a day for a teacher, although the rate can vary according to subject and region, and can go up if an agency knows that a school is desperate. Last year, one school was paying £277 for a science teacher, Tes understands.

Yet the NASUWT survey - of a sample of 1,080 supply teachers - shows that the most common wage is between £50 and £119 a day, and more than a third of supply teachers have had to cut back on food in the past year.

The majority of those surveyed said they hadn’t been made aware by their agency that after 12 weeks of working in the same school they were entitled to the same pay and conditions as permanent members of staff there, and almost a quarter said that placements had been cancelled on or approaching 12 weeks.

“In my last job, they let me go at bang on 12 weeks even though there was only three weeks to go before the end of term,” says John, a teacher from Yorkshire in his fifties.

“I felt gutted when I overheard other teachers in the department saying they were getting someone else in. I’d been doing great and got on really well with the kids.

“What’s more, if the school had wanted to employ me permanently, it would have had to pay a huge finder fee to the agency.

“It makes me sad because I have a lot of skills to offer, but the kids are missing out. I’d love a permanent job and I’ve applied for loads, but at my age I’m lucky if I get an interview.

“Supply teachers are just getting battered. We’re getting used and abused, and the government is just allowing it to happen.”

Exploitation game

There are those, including NASUWT general secretary Chris Keates, who question how the agencies are getting away with making “huge profits” in light of the financial problems facing schools.

“These poor practices are especially driven from exploitative agencies who put their own financial gain ahead of the best interests of both teachers and pupils,” she says.

“This approach not only denies teachers the rights and protections they should be entitled to, but it is also leading to children not having access to quality education delivered by qualified teachers.”

The union is among those calling for the return of supply teacher “pools” run by local authorities, whereby supply teachers were “paid to scale” and allowed to pay into their Teachers’ Pension Schemes (which they currently can’t do if they’re employed through an agency).

Nowadays, just 8 per cent of supply teachers are employed through such pools, according to the survey, and while the reasons for the demise of these systems are not clear, the union says the cuts to local authority funding have something to do with it - and that there’s irony in the fact that some councils are now paying more to supply teacher agencies than it previously cost them to run the pools.

Meanwhile, many schools are happy to let agencies do the work around vetting and interviewing supply candidates, it seems.

“I’ve sent out my CV directly to lots of local schools,” says Mary. “But they won’t take you on unless you go through an agency. The big multi-academy trusts are using the agencies because they do all the work for them. But school leaders should be considering whether agencies are saving them money, and they should be thinking about how they are treating supply teachers, who are their ex-colleagues. They should realise that could be them one day.”

The NASUWT survey also highlights the pressures faced by supply teachers in the classroom, showing that more than a third are kept in the dark about pupils in their class who have special needs and behaviour problems.

And a quarter of respondents said that they had not been told about their schools’ behaviour management policy or who to contact in the event of a problem.

“It made me very upset because they hadn’t prepared me,” says Fiona, a supply teacher who recalls a “terrible” Year 9 geography class with which, she says, the school clearly knew there were issues.

“The school hadn’t even given me a behaviour policy…Yet they knew this sort of thing might happen.” (See box, below.)

Could this sort of treatment spell the end for supply, as more teachers hear of the problems and are reluctant to give up the pay and conditions of their school contracts?

In recent years, some schools have increasingly replaced supply teachers with cover supervisors, and research by the NEU teaching union found that even teaching assistants were increasingly replacing supply teachers.

Stephen Tierney, chief executive of the Blessed Edward Bamber Catholic Multi-Academy Trust, in Blackpool, says cover supervisors employed directly by the trust had originally been brought in to reduce the amount of regular teachers having to cover for absent colleagues.

He adds that they were sometimes a better option than supply teachers, partly because they knew the children and the disciplinary system. “It wasn’t a massive money-spinner, it was just a different way of spending money at that time. The difficulty is that sometimes a supply teacher changes and then you start to think about learning and continuity for a child,” he says.

Attractive prospect?

The NEU teaching union, which itself carried out a survey of 900 supply teachers this year, says that, despite “well-known issues” over pay and pensions, supply teaching continues to attract teachers. There are those who don’t wish to continue, or feel that they can’t continue, in a permanent full-time teaching post, while others can’t get a permanent job.

Meanwhile, the NASUWT research shows that, for the first time in several years, there has been a slight increase in the number of supply teachers being able to work the days they choose, rather than those they are given. The study also suggests that teachers, pupils and parents are all, this year, marginally more appreciative of supply teachers, possibly in light of the recruitment and retention crisis.

Even Mary, who describes the state of supply teaching as “very, very bad,” says: “At least supply teachers are now appreciated more by other teachers. They’re looking at us and realising that we’re coming to their meetings and doing the marking.”

So, if the end of supply teaching isn’t in sight, could we at least see the demise of the disreputable agencies, as more people speak out about the level of “exploitation”?

Mr Tierney says his trust stopped using supply teacher agencies altogether last year after one agency tried to charge fees that it wasn’t entitled to.

“The largest finder fee I’ve heard of was £9,000,” he says. “It was an exorbitant amount, and £5,000 isn’t uncommon either.

“They’d have got away with it for longer if their fees had been more reasonable.”

Last year, a campaign was launched by headteachers’ unions in light of agencies’ large finder fees.

And at the start of this term, the Department for Education set up an online database of agencies that do not charge such fees, which it says is being regularly updated as more agencies are accredited.

The NEU found that more than three-quarters of supply teachers wanted a campaign for higher pay from agencies, while more than half wanted a campaign for national standards for agencies.

The Recruitment and Employment Confederation (REC), which represents supply teacher agencies, says it is “committed to raising standards and sharing good practice” and that it works “with its members to ensure workers were aware of their rights”.

Tom Hadley, REC director of policy and professional services, adds: “We fully appreciate the challenges faced by schools in managing their budgets. However, like any business providing a professional service, recruiters charge fees for their work. These fees cover the extensive checks agencies carry out to ensure that candidates for the role are safe, appropriately skilled and the right match for the school. This involves sourcing, placing and vetting suitably skilled and qualified teachers. Often this is all done at very short notice to ensure cover is provided - for instance, when permanent teachers are ill.

“Recruiters must agree any charges that will apply with the school, otherwise they have no contractual right to claim payment. All REC members must agree in advance written terms with clients that include details of fees.”

Dave Speck is a Tes reporter. He tweets @specktator100

*The names of supply teachers mentioned in this article have been changed as they wished to remain anonymous for fear of being blacklisted by their agencies. The parent company of Tes magazine owns three teacher supply agencies

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters