Teaching science students to reach for the stars

As a statement of intent for ambition in science, it’s hard to beat: a huge image of a space shuttle stretching up three floors. Inside Larbert High, school corridors - traditionally drab and empty - are packed with eye-catching reminders of why the subject matters.

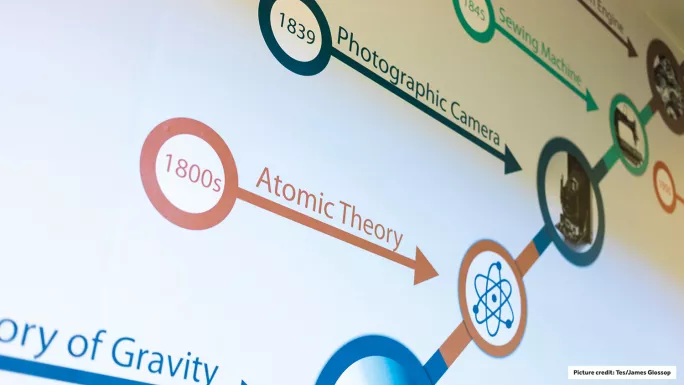

You see dozens of cartoon figures of heroes in the field - astronauts, doctors, chemists and more - and a vertiginous timeline of scientific landmark achievements, from Archimedes’ screw to virtual reality. There’s also a sprawling recreation of the solar system (with a playful addition for any sci-fi fans looking carefully - the Death Star from Star Wars).

Larbert High, in Falkirk, won the science, technology and engineering teacher or team of the year at this year’s Tes Schools Awards, impressing judges with the breadth of its ambition and depth of its teaching. And teacher Ashifa Naseer says that Larbert has another crucial quality: “I think we’ve all got a brass neck - if you don’t ask, you don’t get.”

The school is always on the hunt for funding schemes to improve Stem resources and competitions that could provide pupils with confidence-boosting experiences. Recently, it has been putting a £100,000 award from the Scottish Futures Trust to good use.

One room in the 1,700-pupil school holds 11 3D printers - an example of “university-level resources right from S1”, as one teacher says - where the fruits of pupils’ labours can be seen lying around, whether a spanner, fidget spinner, model building or industrial part.

Similarly impressive is the transformation of a previously workaday classroom into a microbiology lab, an innovation driven as much by Larbert’s can-do mentality as any new pot of money. When health and safety regulations got in the way of plans for pupils to work with staff at nearby Forth Valley Hospital, the school flipped the idea on its head and built its own lab, so that NHS staff could bring their expertise to the school instead.

Sixth-year Advanced Higher biology student Annette Selwyn is one of those reaping the benefits of the microbiology lab. She explains that if, like pupils in other schools, she were travelling to a college or university lab, time would be limited and she would have to stick to tried and tested areas of experimentation. Now, however, biology teacher Eilidh Wilkie says “the pupils can be more creative, have a bit more independent thought”.

Naseer, who is principal science teacher for the broad general education, explains that a culture of innovation is also encouraged among teachers. “If [an idea] is going to have an impact, you can go along with it - you never get shot down,” she says.

Now, Larbert staff want other secondary schools to benefit from their 3D printers and other cutting-edge equipment. Martin Thomas, principal teacher of technologies, says: “We’re incredibly fortunate and it’s now our responsibility to share [these resources] with others.”

That sense of communal spirit also extends to local primaries. Larbert staff run Stem CPD for primary teachers and make up boxes of lab equipment for them. Larbert pupils also work with primary children, who, by the time they move up to the secondary school, are familiar with complex scientific terminology and well-versed in seeing the links between fun classroom activities and potential careers - after all, what else is a marble run than an introduction to rollercoaster engineering?

Amanda Martin, a teacher at nearby Ladeside Primary School, says that primary staff often lack confidence in Stem and oversimplify lessons as a result. Now, however, local primary teachers talk of five-year-olds confidently using terms such as “hypothesis”. “Why not just use the big long words?” says Ms Martin, rather than simpler but less precise language. That approach is backed by the University of Glasgow’s Professor Aidan Robson - who works at the pioneering CERN centre in Switzerland to which he has invited Larbert pupils - who says that scientific language “can be a barrier” that’s hard to overcome after pupils start secondary school.

Primary pupils who excel at science will be encouraged to become part of Larbert’s “Stem Academy”, meaning that, from the moment they enter first year, they will follow a curriculum heavily focused on science, technology and engineering, just as the school has become well known as a centre of excellence for pupils who want to specialise in sports.

Larbert wants Stem pupils to visualise right from the start where their studies might lead them. The school has designed a London Underground-style map of “Stem pathways” to show the huge range of careers that could open up. A Stem “advisory board”, meanwhile, comprises well-connected people in Stem industry and academia. Paul Rodger, principal science teacher for the senior phase, laughs as he recalls that his only experience of “external partnerships” at school was a 1988 visit to the Glasgow Garden Festival.

Headteacher Jon Reid says that pupils working on Stem projects do not work in a vacuum and “always have on the horizon where this might lead to”.

On the day that Tes Scotland visits Larbert High, we meet and hear about pupils - across different year groups - who have created an app for autistic children, investigated potential cancer treatments, designed an oil rig and won a UK-wide competition after inventing an innovative method of flood prevention.

“There are so many opportunities,” says sixth-year student Gavin Kane. “I already knew what an Advanced Higher project looked like before I even got to that level.”

Larbert’s approach to Stem is not simply geared towards those who might gain a PhD in astrophysics, but also pupils who might, for example, aspire to an apprenticeship in the construction industry. One member of Larbert’s Stem advisory is Dale Lyon, of the Concrete Society, who thinks the school has hit upon an important truth: that “closing the attainment gap is not just about qualifications”, but creating as many opportunities as possible for pupils to discover what they like and excel at.

Or, as Lyon more pithily puts it: “Too many schools think about Stem as things that go ‘pop’, ‘bang’ and ‘flash’ - but at Larbert there’s so much more.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters