#ToYouFromTes: The jigsaw children

First, Alice* laughs. Then she suddenly becomes serious.

“No,” she says. “The various agencies, institutions, support services and education bodies involved in supporting me are not joined up. I would say the approach is as opposite to being joined up as it is possible to be.”

Alice is a looked-after child. The shorter list of places in which she has a file under her name includes her local children and adolescent mental health services (Camhs), school, doctor’s surgery, local authority children’s services department, the office of the council’s virtual school head and the county police. The full list runs longer than a tightly-typed side of A4.

For her support to be adequate, at the least, the short list of organisations would need to be talking to each other, discussing her case and creating a holistic plan of action. But they don’t. In fact, they barely talk at all.

Alice’s case may be an extreme example, but the issues she faces can be seen throughout the education system. Schools can’t produce healthy young adults all by themselves - the NHS, housing associations, councils, social care and myriad other services all have a role to play, and with the most vulnerable children in particular.

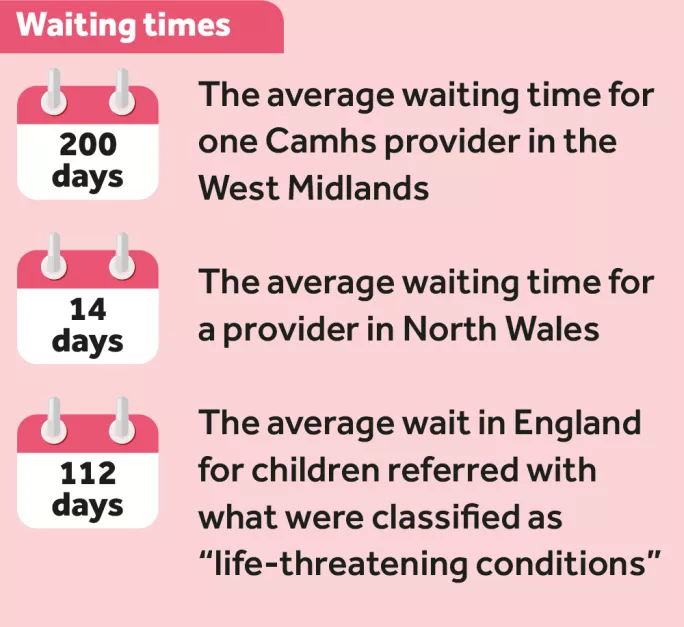

Unfortunately, schools can too often feel that they don’t receive vital support. Thresholds to access Camhs are now higher than ever. Serious case reviews highlighting poor communication between agencies that resulted in a child being failed occur with tragic regularity.

Schools are not off the hook, either: agencies such as the police and health professionals claim that schools do not do enough to communicate in the other direction.

How have we reached this point? And more importantly, can the situation be changed? A growing number of people think it can.

Paul Reville is a former classroom teacher and principal, who is now the Francis Keppel professor of practice of educational policy and administration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It was there that he founded the Education Redesign Lab, which has made breaking down service “silos” its mission. For Reville, the case for joining up education with other services is straightforward.

“We [think] that a pathway to an equal opportunity, meritocratic society is to simply give people a good school,” he says. “Six hours a day, 180 days a year, 20 per cent of their waking hours between [the ages of 5 and 18].” But there’s a problem, Reville argues: “That’s just not enough to level the playing field.”

What happens outside of school is often as important in determining educational outcomes as the quality of teaching a student receives, he argues.

“Students can’t perform if they’re not [at school] owing to health problems,” he says. “Or if they’re so distracted by a toothache, or a mental health problem, a housing problem or a safety problem, they can’t concentrate.”

Often, a school won’t even know about these problems, despite their being addressed by other governmental support services. Sometimes the information will be shared, but then services won’t talk to each other to ensure proper support plans are put in place.

It is often the case that each agency or body involved with a child may hold one piece of the jigsaw of that child’s circumstances, but no one is putting them all together. That equates to a lot of lost time, a great deal of wasted effort, and frequently no one really knowing what is going on. It results in children being failed.

Reville says it’s not surprising public services have become siloed. “Naturally, the range of services provided by government is highly complex,” he explains. “You’ve got to break it down in some way in order to organise it.”

Governments work to “logical categories” - health, education, welfare and so on - but he says problems emerge when these ossify into units that are incapable of working together. “We know of mental health clinics right next door to schools full of kids who need services,” he says. “The clinic is not authorised to provide services in a school setting, the parents culturally don’t want to send their kids to a mental health clinic, and so these two silos stand side by side.”

In the UK, the need to join up education with other services will be no revelation. The former Labour government launched “extended schools”, which aimed to support families beyond the standard school day via breakfast clubs and after-school activities. The idea of integrated services is also at the heart of Sure Start children centres - another Labour programme - which provide help and advice on child and family health, parenting, money, training and employment.

A lack of time and money

However, the momentum behind integration waned following the change of government in 2010. A commitment for all schools to provide extended provision was dropped, with ring-fenced funding for extended schools abolished in 2011 (though most schools do continue to offer some sort of before- or after-school activities).

As for Sure Start, a parliamentary question by the Labour opposition earlier this year found that more than 350 centres have closed in England since 2010, with only eight new centres opening during that period. In total, there are 3,351 centres currently in England.

As mentioned above, anecdotal reports also suggest that communication between the various people involved with a child’s care is worse than ever due to the budget and time constraints that are common across all governmental agencies.

Thankfully, some work is taking place to try to change this on a national level. On both sides of the Atlantic, pilot projects and studies are beginning to emerge. For example, Reville is leading a project with six US cities to join services up. Each city has set up a “children’s cabinet”, bringing together school managers, heads of health and social services, as well as other community leaders, to come up with and implement strategies.

In Oakland, California, “Future Centres” are being rolled out - school-based hubs that provide advice on colleges and careers, help students apply for financial aid and access internships, and which deliver wraparound health and social services. And in Salem, Massachusetts, a website is being built to help parents, teachers and other community members find the best and most appropriate resources to meet children’s needs.

In the UK, some work is also being done to integrate services - in relation to mental health in particular. For example, the government has piloted “lead contacts” within NHS services and schools, and in June, prime minister Theresa May announced the government would be rolling out “mental health first aid” training to staff in secondary schools.

A government Green Paper setting out more radical plans for integrated children’s mental health services is expected by the end of the year. But with government initiatives for the most part remaining piecemeal, agencies and schools are often left to sort out the problems themselves.

An increasingly common solution is home-link roles. Tony Draper is the chief executive of Lakes Academies Trust, which runs two primaries serving a relatively deprived part of Milton Keynes; a past president of the NAHT headteachers’ union, he likens schools to “the A&E departments of society”, scooping up a whole host of acute social problems that haven’t been dealt with elsewhere. He thinks this has become more pronounced in recent years, as austerity has forced other services into retreat.

“A lot of services are being pushed towards schools to sort out because nobody else is capable or willing to see the bigger picture… It’s necessity that is forcing schools into this.”

Like many schools, Draper made the decision to appoint a family support worker; Emma Burrows joined the trust six years ago.

“We needed someone to work with families in need, whether it be on housing, finances, mental health, drug addiction, alcohol abuse,” she recalls.

Burrows now leads a small team working across both schools. The case workers take referrals from teachers or directly from parents. “A teacher may come in: ‘Bobby has not got his socks on, or he’s a bit dirty, he’s always hungry’, things like that,” she explains. “I will speak to the parents to try to get a bigger picture without being too judgmental… because it’s hard for parents in that state to tell people they’ve got no money, can’t fund a washing machine.”

Burrows or one of her colleagues will then work with the family to create a plan to address any issues. If necessary, the support worker will liaise with other agencies.

“It could be as simple as a family not claiming the correct benefits,” she says.

The beauty of this sort of support is that it lifts work off teachers’ shoulders, Burrows says: “They can do what they’re paid to do and teach.”

Unfortunately, those in a similar role to Burrows can continue to be frustrated by the lack of inter-agency working. So could schools push things even further to improve the situation?

Those leading Reach Academy, a free school in Feltham that opened its doors in September 2012, believe so. The all-through school already provides a range of non-educational support to children and families. But it is also in the process of trying to acquire a second site adjacent to the school, in which it plans to create “Reach Hub” - a centre bringing together various service providers under one roof.

“Our aspiration is that we will build this hub where we’ll be able to offer the local midwives a space to do midwifery appointments, and a space to do health-visiting appointments,” says Ed Vainker, Reach Academy’s co-founder and principal. The academy has even spoken to locals GPs about the idea of establishing a satellite surgery, with doctors using the space one or two days a week.

Reach Academy is pushing for integrated services for two reasons, Vainker explains. The first is a “convenience point” - providing a “one-stop shop” where families would be able to access all the services they need, to make life easier for parents who would otherwise have to traipse between providers. But he adds a second, more important reason: joining up services around a child is the best way to guarantee effective intervention.

Vainker gives the example of a five-year-old child who routinely goes to bed at 1am before getting up at 7am. The school becomes aware of this, and is concerned that his sleeping hours are affecting his learning. His parent goes to the GP, believing the child is unable to concentrate because he has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or a special educational need. Rather than leading to an automatic referral to an educational psychologist, a conversation at this point between the school and the GP would flag up the child’s lack of sleep, and as a first step, the parent would receive support to help establish a healthier routine.

The end result: the child’s concentration improves, he does better at school and an inappropriate referral to an overstretched service has been prevented.

One-stop shops for services aren’t new. For example, the Bromley by Bow Centre in East London brings together employment and housing advice, a GP surgery, language learning, a church, arts organisations and a cafe. But Rebecca Cramer, co-founder and secondary headteacher at Reach Academy, thinks schools might be even better placed than health centres to function as community hubs.

“People don’t have to engage with health,” she says. “You don’t have to go to the GP if you’re sick. Whereas you have to engage with education - we see families that the GPs might not see, the dentist might not see.”

Reach Academy’s plans for co-located services at the Hub are still some way off, but the school already offers a package of support to students and parents alike. It employs a family support worker and provides free food to parents who need it via the charity FairShare. It runs adult educational courses and will next year be partnering with the parent-support charity NCT to provide a peer-mentoring project for mothers during the first three years of parenthood. And, mindful of the increasing pressure on young people from social media and stretched NHS services, Reach brought in mental health charity Place2Be from day one.

“Because of the timelines being so long to get Camhs involvement, we feel like we have no choice but to have our own service,” says Vainker.

At this point, some people might ask whether these sorts of activities are really the core business of a school - shouldn’t they be sticking to what they know best: teaching?

“Fundamentally, it is outside their core business,” Vainker says. “All things being equal, every child would come into school, well fed at breakfast, their parents would be comfortable, would have purpose…

“In that scenario, you don’t need to do all those things.”

The problem is, that is not the reality.

Reach is not alone in trying to break down walls - many schools are striving to join up services for their families. Whether it is home support workers or more ambitious projects, though, the challenge of filling gaps in provision is growing.

Valentine Mulholland, the NAHT’s head of policy, says that austerity has not just tipped more work onto schools as other services have been cut but it has also restricted their ability to respond. “Schools have had to source services themselves,” she says. “The problem we now have is that the funding crisis is making that much more challenging.”

Funding pressures mean schools are struggling to retain existing staff, let alone employ new family support workers.

Another barrier, Mulholland says, is that school leaders often lack the headspace to think about integration because they’re preoccupied with other things - not least delivering academic results and staying on the right side of the accountability regime.

“The punitive accountability system that we have means it’s easy to focus very much on that,” she says.

Reach Academy’s leaders are aware of their privileged position as a new free school. “We are fortunate because we started from scratch,” admits Cramer. “We haven’t inherited lots of legacy financial issues.”

From the beginning, the school decided to employ a family support worker, rather than an additional teacher.

“We put those things on the budget and we say we’re not taking them off, and then we work around it,” says Vainker.

But while he appreciates money is tight and most other heads won’t have the luxury of starting with a blank canvas, Vainker thinks investment in wraparound services has the potential both to save schools money and deliver the results demanded by the accountability system.

He gives the example of two students at his school on very different trajectories*. The first is a girl who is now in key stage 2, “still behind, although she’s caught up a lot”.

“When we met her, she couldn’t speak at all, she just sat in front of the TV,” says Vainker. “There were no toys in the house; it was incredibly barren.”

Her 18-month-old brother had a similar home environment. The school bought toys and the family support worker would go to the house once a week, playing with the toys and modelling this to the mother. She got the little boy into a “stay and play” and encouraged the mother to take a course to develop her English.

“[The boy] is now in key stage 1 and has exceeded all the early learning goals, so he’s on a completely different path to [the other child], who we only encountered in Reception,” says Vainker. Moreover, he now requires “zero additional intervention”, while the older girl is still getting “a huge amount of one-to-one”.

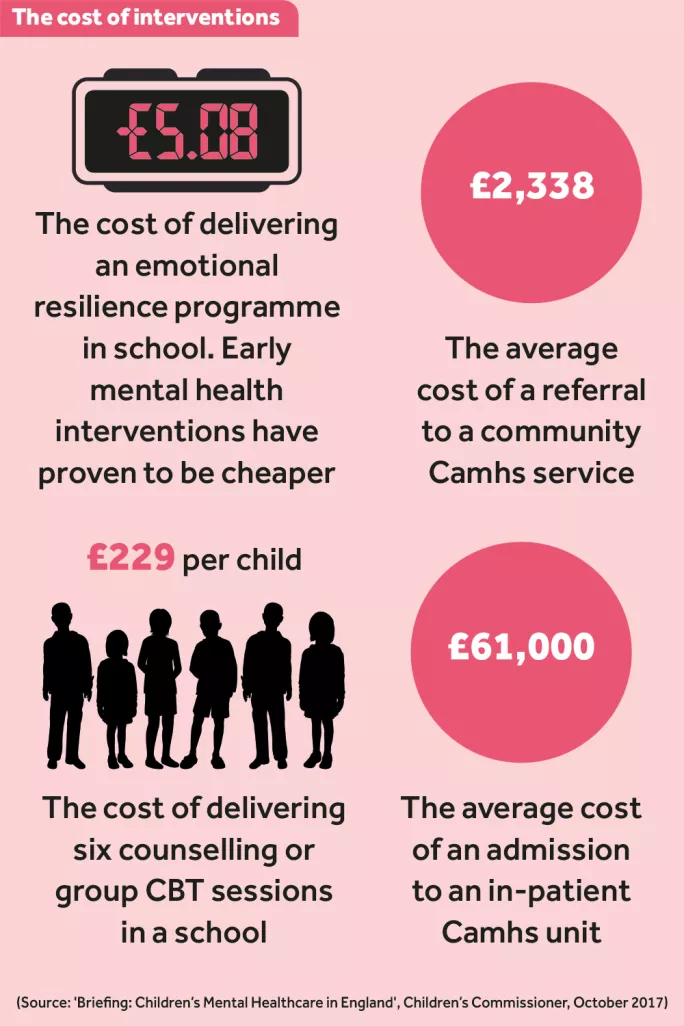

“It’s a cliché, but we think that early intervention definitely pays - it yields a financial return,” he says.

It’s good to talk

It’s a similar story for mental health interventions, Vainker argues. “If we’re able to support a child in secondary who’s really struggling in terms of their mental health before things get to a crisis point, that’s going to mean our senior staff are not tied up supporting that child further down the road.”

As for the accountability system, while it’s still early days for Reach Academy, it came fifteenth in the Progress 8 table with its first set of GCSE results. “If we look at that cohort of children, they received a huge amount of what we would say is additional support,” he points out.

But funding and accountability are not the only barriers to cooperation. Perhaps the most fundamental obstacle is poor communication between services.

Jac Ragozzino, director of inclusion at Lakes Academies Trust, says her trust is “very open to working with other professionals”, but sometimes encounters “a barrier from the other side”. In particular, well-meaning concerns about protecting patient confidentiality often hamper information sharing. Ragozzino says Camhs workers will occasionally come to the trust’s schools to observe children and ask teachers to fill out assessments, but then won’t share the findings with the school. In one case, a clinician recommended a pupil went on medication, but the first thing the school knew about it was when “mum turned up with tablets one day”.

Unfortunately, you often hear counter-claims that the school seat at local multi-agency meetings sits empty, too.

A lack of communication between schools and other agencies is not universal, though. In specialist education - special schools, pupil-referral units (PRUs) and the like - a whole view of the child’s care from multiple perspectives is common, often because the situation or needs of the child are critical enough to force cooperation.

Ollie Ward is a maths teacher who currently works at the Key Education Centre, a PRU in Gosport, Hampshire. Prior to this, he taught in both mainstream secondary schools and a school for pupils with profound special needs. When it comes to partnering with other services, he believes the mainstream sector could learn a lot from specialist education.

“The special needs school…they had such close links [with service providers],” he says. “It was so well drilled, because it had to be.”

Likewise, his PRU works closely with the police, the youth-offending team and other local services.

He says he’s dismayed by what he sees in mainstream settings: “It is quite shocking to go into some schools and see even their inclusion teams don’t really have much of an idea about the risk factors in a young person’s life.”

One project that aims to push the special-school connections even further is run by Bradford Council, which has recently drawn up plans for a social, emotional and mental health-needs free school. Complete with a residential facility on site, the school will offer a range of health and therapeutic interventions alongside its teaching.

If such initiatives work in settings where the need is most critical, then it shows that it is possible to make these connections. Could it be that many of the problems in less severe cases, then, are simply down to mindset?

“Instead of thinking about what’s convenient for those who are funded by taxpayers to provide a service, what about starting with the ‘client’?” asks Reville.

The first step, he says, is to view every child as being in a “developmental pipeline” that begins before they are born and ends when they emerge as an adult, ready to go to university, start an apprenticeship, get a job or otherwise contribute to society.

The second step is for teachers and other professionals to ask themselves which support services each child and family needs at every stage along their journey to successfully get to that end point.

“If we think of it in that way, then that forces the integration of services,” he says.

But the fact remains that much of this will have to be driven from central government. A strong central figure or body is needed to corral providers, get professionals to sit around the same table, and ensure the right funding streams and IT systems are in place to support new ways of working.

In the US, Reville’s projects are being coordinated by city mayors. With the election of “metro mayors” in Greater Manchester, Liverpool, the West Midlands and elsewhere, perhaps these high-profile figures will one day also call the shots in England, too. Until then, to prevent young people from being failed, it seems that central government will have to shoulder the burden of joining up our fragmented public services.

*Personal details have been changed to protect the students’ anonymity

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters