Victims of pupil violence ‘don’t get proper support’

Secondary teachers report that verbal abuse by pupils has become commonplace and failure to tackle physical violence is leaving them increasingly vulnerable, Tes Scotland can reveal.

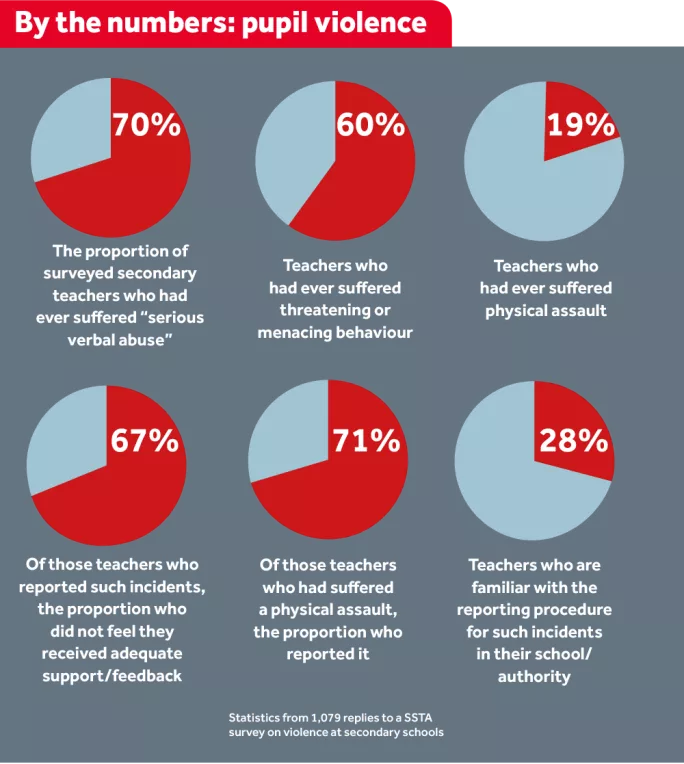

A Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association (SSTA) survey of 1,079 of its members has identified concerns that many teachers do not receive adequate support after incidents of violence or abuse. The survey also shows that inclusion policies often leave teachers without the protection from violence that other professions - and council employees - routinely expect (see pages 8-9).

General secretary Seamus Searson says the survey confirms “the regular reports we have been receiving from members of the increasing problem of poor behaviour in schools”.

In the SSTA survey, 19 per cent of respondents reported that they have suffered a physical assault in their career, while 70 per cent have experienced serious verbal abuse. Yet it also shows that teachers often do not report such incidents - only 28 per cent are familiar with reporting procedures, which are widely criticised as opaque and cumbersome - and only a third who did report felt they received adequate support and feedback. Some of the more extreme incidents reported in the survey include:

- * A pupil throwing a chisel at a teacher.

- * A drunk and disruptive pupil being removed from a lesson but returning to it after sobering up.

- * A teacher receiving no feedback after reporting that a pupil had carried a knife into the classroom.

- * A one-day exclusion for a male pupil who punched a female teacher in the stomach then repeatedly punched a male colleague who came to her assistance.

- * A probationer who talked to senior management about going to police over concerns about sexual harassment by a violent pupil, who had filmed the teacher, but found the pupil back in their class the next day.

One teacher said that their old school was simply “not a safe place”, while others were told by school senior management that verbal abuse was now “part of the job”; many complained that being told to “fuck off” no longer led to consequences for pupils.

One teacher said: “Although the victim of acts of violence, I was often made to feel by managers at all levels that I was somehow to blame for the incident.”

The concerns of many teachers were summed up by one who said: “There is a worrying culture of abuse towards staff in my school now, which has come as management have become increasingly reluctant to use sanctions for serious incidents.”

Searson says: “Headteachers and teachers feel unsupported in trying to maintain good discipline. The constant statistical drive to reduce exclusions is putting tremendous pressures on schools and teachers.

“Exclusions have become seen as a teacher and the school failing, when in reality it is showing that schools, following years of staffing and funding cuts, are unable to meet the needs of all their pupils.

“These pupils become frustrated and disillusioned and ‘hit back’ at the teachers and education support staff in schools.”

He adds that the number of teachers who feel that schools try to “sweep [violent incidents] under the carpet” is “alarming”. “It is no wonder that teachers are leaving our schools when levels of poor behaviour and lack of support is a regular occurrence in schools.”

But Maureen McKenna, president of education directors’ body ADES, rejects the idea that local authorities and heads are sweeping problems under the carpet. “There will always be a time when, for the safety of the pupil themselves or of others, that a pupil needs to be excluded,” she says. “However, we need to ensure that we are excluding for the right reason and for the right length of time.

“The cause of behaviour that led to the incident needs to be fully explored. This must involve both teachers and young people reflecting on their respective behaviours.”

Permanent exclusions have become extremely rare in Scotland, but McKenna says exclusion can still be “a very powerful deterrent” if it is “used wisely and when all understand the reasons behind the exclusion”.

McKenna is education director in Glasgow, where she says there has been “extensive training” in recent years - including one course called All Behaviour is Communication - to help school staff understand the underlying causes of poor behaviour, which is “particularly important in a city where so many of our children and young people experience trauma in their lives”.

A Scottish government spokesman says: “The majority of school heads and teachers believe that most pupils are well behaved in classrooms and around the school.

“However, we want all our children and young people to behave in a respectful manner towards their peers and staff, and no teacher should have to suffer abuse. Our refreshed guidance on preventing and managing schools exclusions, published last year, includes guidance on managing challenging behaviour.”

He adds that the government’s Behaviour in Scottish Schools research report, published in December, said that, in a representative survey, 2 per cent of secondary teachers reported that they had experienced physical assault in the previous year.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters