What the pay deal means for your school

As the classroom clock ticked down to the end of term, tension had been rising.

With many school budgets already at breaking point, heads had no idea what kind of pay rise they would be able to give their teachers in September or, crucially, where the money would come from.

While the Department for Education wrangled with the Treasury over who would fund a deal for teachers, schools feared a doomsday scenario of a big pay rise without the cash to fund it.

So when NEU teaching union activists protested outside the DfE’s headquarters in the final week of term, talk of strike ballots was in the air.

“We are going to show them that the anger will be now, and it will grow across the summer. We are going to come back and we are going to be more angry about this whole thing,” joint general secretary Kevin Courtney said of the possibility of an unfunded pay rise (see bit.ly/SummerAnger).

A week later, the DfE sprang its announcement on the day MPs went on their summer holidays: teachers would receive up to 3.5 per cent.

Following that news, although Courtney still argued that the deal was not good enough, his rhetoric had shifted. “We will consult with our national executive in the autumn term about the best next steps to take,” he wrote on the NEU website (bit.ly/NEUSteps).

As the dust settles on an announcement that was more nuanced (or divisive) than expected, the DfE may have done enough to avert a nationwide strike by teachers. But that doesn’t mean schools are jumping for joy - far from it.

On the face of it, the DfE’s job was to address a very simple question: how much should teachers and school leaders be paid? But, in reality, the decision would have a profound effect on some of the biggest issues facing schools today.

So what does this year’s pay award mean for teacher recruitment and retention, school funding, and industrial relations?

First, a reminder of the settlement itself.

After months of data analysis, school visits and deliberations, the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) made a simple recommendation: “All pay and allowance ranges for teachers and school leaders are uplifted by 3.5 per cent.”

Beyond the headlines

The DfE’s response won headlines saying teachers would get a 3.5 per cent rise, but the small print revealed that leaders and those on the upper pay range would actually get 1.5 per cent and 2 per cent respectively. The Institute for Fiscal Studies noted that three in five teachers would suffer another real-terms pay cut.

And while the DfE said the pay increases were “fully funded”, this was a novel interpretation of the phrase, designed to hide the fact that schools will have to fund the first 1 per cent from their existing budgets.

What does the offer mean for teacher supply?

When then-education secretary Justine Greening handed the STRB its remit, she asked for “an assessment of what adjustments should be made to the salary and allowance ranges for classroom teachers, unqualified teachers and school leaders to promote recruitment and retention”.

Through his response to the STRB report, her successor Damian Hinds last week signalled that recruitment and retention of the former two groups was more important than the latter. It was not a distinction that STRB made.

When Tes asked Hinds why he was giving some teachers a real-terms pay rise, but their more senior colleagues a cut, he pointed to the public finances: “The pay cap has gone but we are still in a financially constrained position,” he said.

The risk is that, while a 3.5 per pay rise for teachers on the unqualified and main pay ranges may help to tip the scales when young graduates weigh up whether to join or stay in the profession, it could have the opposite effect when it comes to leadership.

The STRB report was clear that few classroom teachers it talked to wanted to become senior leaders, and few assistant and deputy heads wanted to become heads. For teachers on the main pay scale, another year of watching senior colleagues’ salaries fall further behind will give them little incentive to push for promotion.

Hinds appears to have calculated that younger teachers are more salary sensitive, while leaders who have invested a greater number of years in their careers are more likely to carry on, even through gritted teeth. Or, as Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT headteachers’ union, puts it: the government feels it can “take school leaders and teachers for granted for another year”.

This is, of course, assuming that teachers and leaders do actually receive the award the government announced. Union leaders say the heads of some schools in straitened circumstances have already told teachers they cannot afford to pass on the pay award, despite the funding the government is providing.

So what does the pay award mean for the other great pressure on schools: funding?

Compared with the scenario of a big unfunded pay rise that kept heads and school business managers awake during the last weeks of term, the settlement is undoubtedly good news.

The DfE’s £508 million grant to fund the pay awards for all teachers - not just those at the top and the bottom of the ranges, and including costs like National Insurance and pension contributions - means schools that have already seen funding fall by 8 per cent in real terms since 2010 should not have to make further cuts to give staff a rise.

Show me the money

The problem is that, while we know the extra £508 million will not come from the Treasury, we do not know in detail where within the DfE’s budget it will be found. The department carefully says no cuts have been made to existing programmes, but many still fear schemes to help struggling schools and areas improve will take a hit.

Surprisingly, some schools may actually reap a small financial dividend from the pay award. If they had budgeted for a 2 per cent pay rise, as recommended by the NAHT, the government funding for everything above 1 per cent could add a few thousand pounds to their pot.

But by the same token, schools that were so stretched that they could not budget for even a 1 per cent rise will suffer another blow.

And the late timing of the announcement could lead to short-term difficulties.

Although the DfE says schools will know in September how much grant they will be getting, the actual payments will not arrive until later in the autumn term. “There is going to be a cashflow issue,” warns Valentine Mulholland, head of policy at the NAHT. “It may cause problems because we have got so few schools that have reserves now.”

At the confluence of these three big, interrelated issues - pay, recruitment and funding - lies the answer to the big question that has hovered over the hot summer like a storm cloud waiting to break: will teachers strike?

In this respect, the DfE may have played a difficult hand nimbly, forcing the unions into a dilemma: do they claim victory for their long campaign for a DfE funded pay rise, or do they go to war over a deal that falls short of their 5 per cent demand and sees most teachers get less than inflation?

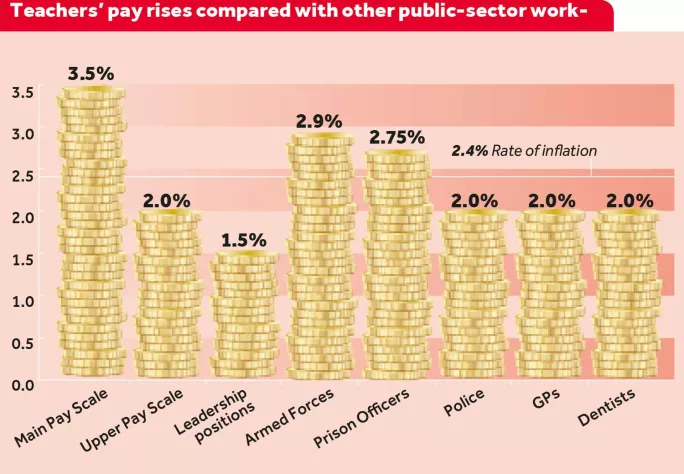

In the court of public opinion, they may struggle for support if they opt for the latter. Compared with the rest of the public sector, main-range teachers have done well. The Armed Forces (2.9 per cent), prison officers (2.75 per cent), police (2 per cent), GPs (2 per cent) and dentists (2 per cent) all lag behind (see graphic, below left). And the Treasury’s promise of £508 million makes it harder for unions to hitch the issue of teacher pay to their existing, and effective, school cuts campaign.

NEU joint general secretary Mary Bousted points to the positives. “The 3.5 per cent awarded to main-scale teachers is a belated recognition by the government that we have a teacher-recruitment crisis. It’s the biggest public sector pay award,” she notes.

Nevertheless, the decision to restrict the real-terms pay rise to teachers on the unqualified and main pay ranges “is a huge mistake”, and the NEU will “campaign” for all teachers to receive the STRB’s recommended increase.

Mulholland does not close the door fully to strike action. “I don’t think that we have secured sufficient to say that that is completely out of the question, but only the NEU and NASUWT [teaching unions] can confirm that, really,” she says.

But the government’s announcement, including what unions brand “divide and rule tactics”, can only have made it harder to clear the already intimidating hurdles that stand in the way of such industrial action.

The Trade Union Act, passed two years ago, makes it significantly harder to win a strike ballot. Not only does it require a turnout of at least 50 per cent; when it comes to schools, at least 40 per cent of all eligible members must also vote “yes”.

The nightmare scenario for the unions would be to hold and then lose a strike ballot, damaging their credibility with the government. Calling a national vote would be a big risk. Local action at any individual schools that did not pass on the pay rise looks more possible.

The summer of anger looks set to become an autumn of consultation and uncertainty.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters