What would it take to rescue schools from this cash crisis?

School budgets have reached a crunch point; following more than a decade of steady increases, government funding is no longer keeping up with rising costs.

Now, after months of being overshadowed by NHS cuts, a parallel crisis in schools has become a key general election campaign issue. Pressure is rising for politicians to plug the gap. But even if they do, real damage has already been done.

How did we get to this point? The downwards trend in real-terms school budgets started two years ago, after the 2015 general election. And it should perhaps have come as no surprise.

After all, former prime minister David Cameron had admitted during the election campaign that his government would not commit to increasing school funding in line with inflation.

But it was a big departure from the coalition government’s decision to protect parts of the education budget - including schools - from cuts by increasing spending in line with rising prices. And it was an even bigger reversal from the significant increases enjoyed by schools during the spending boom under the New Labour government.

The stark change was spelt out recently in a briefing paper by respected thinktank the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), which calculates that, between 2015-16 and 2019-20, schools face a real-terms cut of 6.5 per cent, taking into account general inflation - or 8 per cent, including rising costs such as pensions and national insurance.

‘The largest fall since the 1970s’

The IFS says this represents “the first real-terms cut to school spending per pupil since the mid-1990s and the largest fall over a four-year period since at least the late 1970s”.

As we know from the National Audit Office’s report last December, this will require £3 billion in savings from schools by 2019-20.

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats are campaigning on reversing this £3 billion gap, and as Tes went to press there were suggestions that the Conservative leadership was considering offering schools more money to soften the financial blow.

The situation is complicated because, on top of real-terms budget cuts for schools, a new national schools’ funding formula is supposed to be on the way. The scheme is aimed at achieving a fairer distribution of funding. But its introduction with no extra money would leave many schools across the country facing a double whammy of cuts.

Last week, on the front page of the London Evening Standard, a succession of Tory MPs complained about the formula.

Conservative backbencher Geoffrey Clifton-Brown was quoted as saying: “The absolute minimum in the manifesto should be that no school loses out in cash terms [because of the formula].”

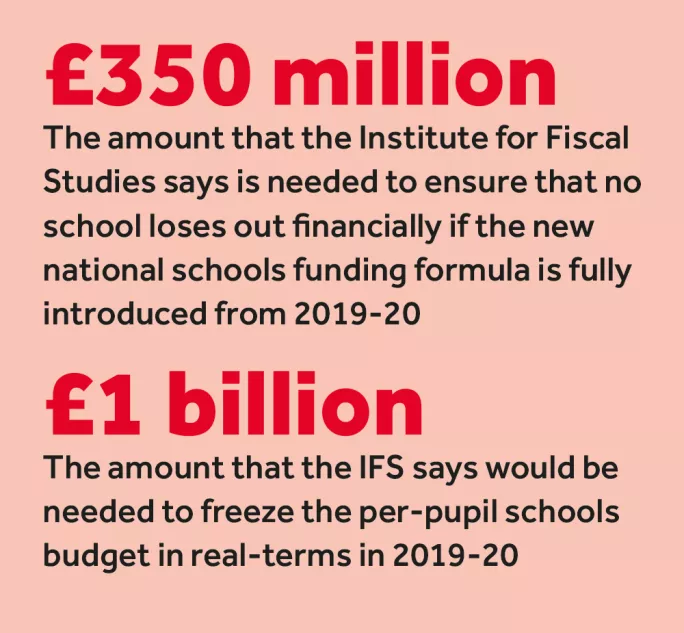

What would it take to fulfil his wish? Possibly not as much as one might think. IFS data shared with Tes suggests that the government would need to pledge an extra £350 million to ensure that no school loses out financially when the formula is fully introduced in 2019-20.

The popular option?

Of course, that wouldn’t prevent schools from losing out in subsequent years, or protect them from real-terms cuts, but it would potentially make for a crowd-pleasing manifesto promise.

However, it also would involve protecting schools currently deemed to be “overfunded”, possibly to the consternation of heads in parts of the country that have been historically “underfunded” - many of which are Conservative areas.

Professor Tony Travers, of the London School of Economics, calls £350 million “fairly marginal in public finance terms”. “The truth is that governments can find pots of money here and there if they choose to,” he says.

Travers suggests that the £350 million could be “tapered” in future years, meaning that it would be reduced gradually to avoid a sudden funding cliff edge.

But this would do nothing to protect schools from real-terms cuts. To freeze the per-pupil schools budget in real-terms would cost an extra £1 billion in 2019-20, according to a separate IFS analysis published last month.

Where could this money come from? Labour and the Liberal Democrats are confident they can find it.

But under the Conservatives’ plans to date, health and policing are off limits, and there is arguably little spare cash left to prise from local government budgets.

“The most likely outcome is the government will feel it can choose to tolerate a slightly higher deficit for a while,” says Travers. But even if the next government does choose this path, it will come too late for many schools.

Russell Hobby, general secretary of the NAHT headteachers’ union, says any funding increase would be welcomed, but many heads have already had to work the cuts into their future budgets.

“I wouldn’t want to look a gift horse in the mouth, but schools are planning hard now, and trying to second-guess what the policy of the month is going to be makes planning really hard,” he says. Adding more money now will also fail to help the heads who have already had to hack at their budgets, the pupils at their schools - or the teachers who have lost their jobs.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters