Where will we find a further 47,000 secondary teachers?

Teachers have known for years that their profession is in the throes of a recruitment and retention crisis. But they might not realise just how bad the shortfall of teachers is about to become. Exclusive research by Tes shows that England needs 47,000 more secondary teachers by 2024 if it is to cope with an explosion in the number of pupils.

To put that into perspective, the figure represents a 22.5 per cent increase in the number of secondary teachers currently in the system - at a time when recruitment for new trainee teachers is already going backwards.

The analysis also reveals that the government is now faced with a stiff challenge if it is to hit its target for teacher enrolment in some key subjects. In modern foreign languages, for example, nearly a quarter of all suitably qualified MFL graduates would have to be signed up each year.

These bombshell figures pose stark questions for the government. Could the Department for Education somehow beat the odds and find enough teachers to plug the looming gap? And if not, does it have a Plan B? Might schools have to let class sizes rise or could they even have to resort to lessons without teachers?

The government’s standard response whenever people talk about a teacher recruitment and retention crisis is to say there are “more teachers in our schools than ever before”. Asked to respond to this story, the DfE did exactly that. It added that there are 15,500 more teachers than in 2010 and that new staff outnumber those who leave.

While this is technically true, the picture it suggests is distorted; the looming recruitment disaster is concealed by opposing trends within primary and secondary schools.

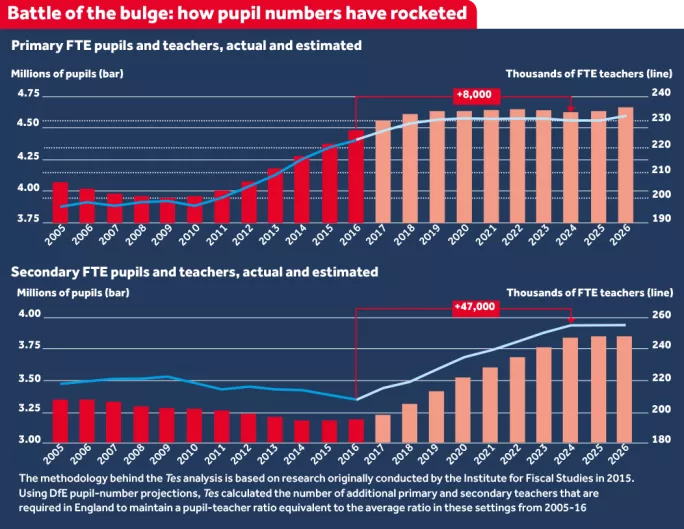

In primary schools, the number of teachers has indeed expanded considerably in recent years. From a low of 196,400 in 2010, it has since ramped up to 222,300 in 2016 - the latest year for which figures are available. This is in line with an increase in the number of primary pupils, which has risen each year, from 3,947,450 in 2009 to 4,479,325 in 2016.

Following years of growth, the primary population is expected to stabilise in the coming years. If the government wants to keep to the average pupil-teacher ratio that it has maintained since 2005 (20.1 pupils per teacher at primary level), it will still have to add nearly 8,000 teachers by 2024.

That won’t be easy. According to the latest figures from Ucas, applications from people wanting to train as primary teachers have fallen by 26 per cent on the same point last year.

But the challenge of recruiting 8,000 more primary teachers looks straightforward compared with the onerous task facing the secondary sector. While the overall number of teachers in English schools has gone up, the increase in primary teachers has masked a decline in the number of secondary teachers. Since 2009, the number of secondary teachers has fallen from 222,400 to 208,100 in 2016.

Secondary schools are already feeling the recruitment crisis bite. Getting hold of good teachers is now “a lot more challenging”, says Arwel Jones, headteacher of Brentside High School in London. He says that even subjects such as history - which were “easy” to recruit to a few years ago - are now proving tricky.

The effect of the crisis has been softened by a decline in the secondary pupil population, which has fallen from 3,348,950 in 2005 to 3,180,175 in 2014. But now, as the demographic bulge in pupils moves from primary into secondary, the trend has been jolted into reverse: the number of secondary pupils is expected to steeply climb to 3,838,700 by 2024.

This means that to stay in line with the average secondary pupil-teacher ratio since 2005 (15.1 students per teacher), the number of teachers would have to rocket by nearly 47,000, from 208,100 in 2016 to 254,822 by 2024. That’s an increase of over a fifth. And it’s against a backdrop of applications to train as a secondary teacher falling 16 per cent year on year - and at a time when the DfE has missed its own teacher-recruitment target for five years running.

Worse still, schools could be hit with a demographic double whammy. While the number of secondary students is set to increase, a fall in the number of 18-year-olds this year will mean a smaller pool of potential new teachers to draw from in the future.

If the situation didn’t already look dire, it’s thrown into even starker relief by the existing monumental recruitment challenge facing some subjects. In MFL, the DfE has a target of recruiting 1,500 new teachers in 2018. The problem is, only about 6,200 MFL degree holders graduate with at least a 2:2 grade each year. This means 24.2 per cent of all such graduates would have to opt for a career in teaching to meet demand. In maths, the proportion is even higher, at 40 per cent of all graduates, though this is distorted by the quirk that subjects such as engineering - which in practice are suitable for a career teaching maths - are not technically deemed by the DfE to be relevant degrees; in English, it’s 17 per cent of all graduates with relevant degrees.

Perhaps the most frightening aspect of the Tes analysis is that 47,000 extra teachers is the net increase that is required - the figure does not take into account the teachers leaving the system who will need to be replaced. As the National Audit Office (NAO) has reported, the number of qualified teachers leaving state schools before they reach retirement is on the rise, increasing from 9.3 per cent of the qualified workforce in 2011 to 9.9 per cent in 2016 (more teachers are also returning to teach in state schools than in the past, but not enough to compensate for the early retirees).

The severity of the crisis highlighted by Tes has been greeted with alarm and dismay by education unions. Geoff Barton, the general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, calls the figures “eye-watering”. The NEU teaching union’s joint general secretary Mary Bousted says they are “potentially catastrophic”.

So what is to be done? The one ray of light in an otherwise gloomy scene is that most people agree on the key actions that are needed to boost teacher supply. Better pay for teachers is the first ingredient - though whether the DfE would be able to find enough cash to make a difference is another question.

The second big thing that might ease the situation would be a cut in teacher workload. That could both help limit teacher turnover and neutralise one of the major factors putting people off entering the profession.

Workload woes

Education secretary Damian Hinds said only last month that he regarded workload as “one of the biggest threats” to teacher recruitment and retention.

The unions, unsurprisingly, feel the same way. “Workload becomes ever more important,” says Barton. “We need to paint a far more optimistic picture of teaching than we have.”

Bousted agrees: “[The government] has to make teaching more attractive a profession, and to do that, it has to tackle excessive workload.”

Action on these fronts would give retention a much-needed shot in the arm, which would stop the projected gap in teachers growing even further. Education Datalab estimates that if the government had been able to maintain retention rates at the level of 2009, there would be 4,398 more teachers in our schools today.

Higher pay and lower workload may be the two most important changes needed to attract extra teachers, but there are other things the government could still do to boost supply. Barton says “simplifying routes into teaching” would make a difference, as would “making teaching more flexible” to accommodate those who want to work part-time or job share.

There are belated signs that the government is waking up to the crisis. Hinds has pledged to “strip away” unnecessary workload, and promised a teacher recruitment and retention strategy. But it is difficult to shake the feeling that it could all be too little, too late.

“If you look at the [government’s] strategy, it’s just a mixture of current initiatives, which the NAO has said are small scale,” says Bousted.

Patrick Roach, deputy general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union, says that government policy to date has been “piecemeal”.

Asked whether the extra 47,000 teachers could be found, Barton seems unwilling to give up the ghost just yet, although he admits it will be a “Herculean” task. But Bousted is already willing to call it - she thinks it is simply unachievable. “It’s just untenable that you’re going to recruit those numbers,” she says.

If so, the government will now have to give serious consideration to a Plan B.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters