Why it takes a global village to teach a child

“There, in his noisy mansion, skill’d to rule,

The village master taught his little school;

A man severe he was, and stern to view,

I knew him well, and every truant knew;

Well had the boding tremblers learned to trace

The day’s disasters in his morning face”.

Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village, 1770

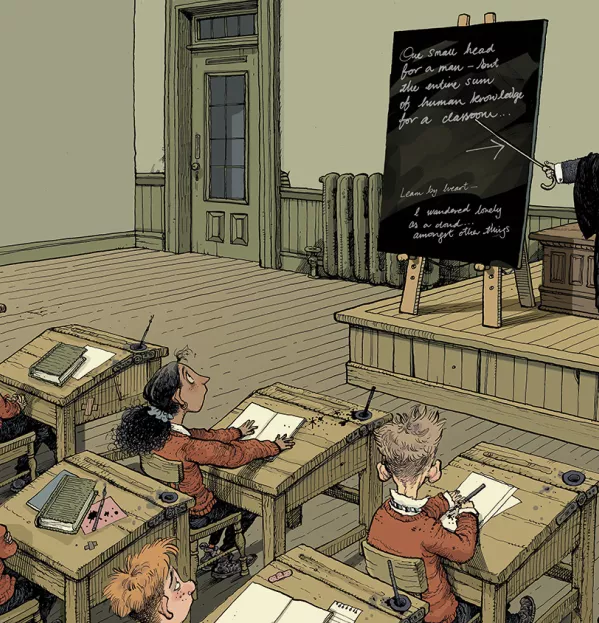

There are certain lines and ideas that never leave you. Mr Hennelly taught us The Deserted Village in Year 8, sitting at his desk, set high above the rows of bowed boys’ heads. We read the poem and learned, after a fashion, and from a teacher who would not have been out of place in Goldsmith’s context.

This is no slight to Mr H. I loved him and I loved English lessons. What we did didn’t seem like learning: it was free from the drudgery that filled so many of my other lessons, so it couldn’t be learning, could it? These classes were engaging, stimulating. The “boding tremblers” were taught in rows and by rote because that was the way it had always been done. There was little room for development because the exam results were good and it all seemed to work effectively. I went to a good school - it is still a good school, although I expect for very different reasons.

Goldsmith decried the industrialisation of the landscape. He saw the bucolic dream begin to change and he foresaw disaster.

He was right in many respects, but not in all. The Industrial Revolution brought and sustained the education system I grew up in. It answered a need for literacy, not liberalism. What it spawned, however, was an unintended atrophy, which has been challenged more profoundly in our digital age than at any time in the past. But, to be fair, this challenge has been continuing for the past 20 years, and improvements in curriculum design and pedagogy are the prime movers of change.

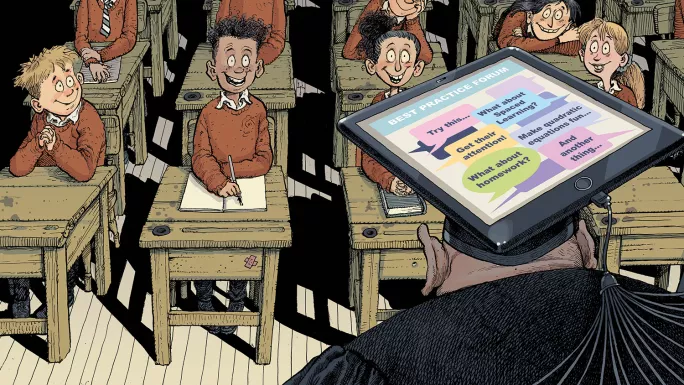

For my money, the biggest single influence on effecting change has been the collaboration, via social media, among and between professionals in a digital learning community. This is one of the best adverts for online media. Engaging with the experience and research of others, as well as our own research and development in school, allows us to put excellence into practice in an authentic and meaningful way.

It behoves educators, therefore, to examine what makes good practice, and to question in what context and in which ways excellence can be incorporated into the daily business of teaching and learning.

One way - perhaps the most obvious one - to determine levels of success is to look at examination results. Lucy Crehan spent a month in five different education systems that regularly come top in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Pisa (Programme for International Student Assessment) tables. In her book, Cleverlands, she shares some of the strategies that the world’s top-performing and equitable systems have in common, such as mixed-ability classes, where all pupils are expected to work to the same high standard, creating the tide that lifts all boats. Although this may seem counterintuitive, one cannot deny the value of reflecting on one’s own practice and comparing it with the places that, year after year, top the world’s rankings in maths, reading and science.

‘Teach as if no one’s observing’

“Exams results aren’t the be-all and end-all,” I hear you say, and quite right, too. To be fair, I don’t think Crehan is suggesting they are, but this is a worthwhile preoccupation.

“How can teachers be the best they can be when they are hemmed in by performance measures that focus on short-term and easily quantified outcomes, like lesson observations and exam results?” asks Dr Kevin Stannard, director of learning and innovation at the Girls’ Day School Trust. To Stannard, the important thing is to dance as if no one is looking - or, in our context, to teach as if no one is observing - encouraging great practice that ticks the performance and assessment boxes almost in passing.

Ann Mroz, editor of Tes, administered a dose of reality recently (bit.ly/TeachersContent), suggesting that emulating, let alone surpassing, top-performing environments becomes a pipe dream if teachers aren’t content in their work, confident in their knowledge and competent in their craft.

But there are numerous other factors that contribute to putting excellence into practice: almost too many to know them all. Almost. While accepting the Socratic premise that the more we learn, the more we are likely to find our knowledge lacking, we must be careful not to capitulate on our quest for excellence. Yes, of course we can’t possibly know everything - we’re only human after all - but that doesn’t mean we should stop trying to raise the tide.

The Deserted Village continues: “And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew/That one small head could carry all he knew.”

We all gazed as Mr H ran his course but, in a way, that approach has become archaic now. In a digital world imbued with the epistemic certainty that we may not even know what we don’t know, there has never been a time when we were in greater need of research and informed, evidenced-based practice.

Mr H was immune to changes to the curriculum and trends in pedagogy, but the boding tremblers of Goldsmith’s village are not today’s scholars in a digital world. Nor are we, as professionals, as isolated and insulated from pedagogical developments - and a good thing, too. In my reading and at my school, our endeavours are driven by one guiding principle: what is best for the children?

Unless, as professionals, we engage in evidence-based research - unless we belong to and actively support peer-to-peer review - we risk being hostage to the fortunes of fads.

What works in one context may not work in others, but we need to have a wide canvas to engage with. Through social media and peer-to-peer conferencing focusing on core classroom concerns, through the collective drive to share evidence-based practice and seek the best for everyone, the classroom of today is very different from Mr H’s and our global village is far from Goldsmith’s.

Cliff Canning is headmaster of Hampshire Collegiate School. He tweets as @HCSLearning

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters