Why misbehaviour isn’t simply a free choice

You’re on duty in the playground and say hello to Amy, who is due to be with you for an English lesson straight after break. Soon after the bell sounds you notice Amy is last to leave the playground, so you usher her in with a cheery, “Best get a move on so you aren’t late to my lesson, Amy!”

But she starts to go the long way around to your classroom. You point her in the right direction, but she says, “I left my bag in Mr Khan’s classroom.” And then she’s gone.

It’s 10 minutes into your lesson and Amy is not there. But then you see her at the door minus her bag, accompanied by the deputy headteacher. Amy had been wandering the halls. She strides in, slumps at her desk and refuses to do any work.

On this occasion, you opt to deal with the tardiness later and instead get her started on some work. You remind her of what is required and give her some take-up time by turning to talk to students at another table.

Within a second, Amy sweeps her work onto the floor with both hands, tips her chair over, and on her way out of the room she leaves you with “I’m not fucking doing it!”

As teachers, we are united in accepting that this behaviour is not OK and equally united in agreeing that disruption-free learning is a right for all children.

But we don’t all agree on how to respond to pupils like Amy because we differ in how we look at children’s behaviour, and this influences and informs how we respond.

In this situation, an obvious and common response would be a sanction, as dictated by the school’s policy. The logic goes that sanctions help children make better choices and provide clear boundaries, and if those sanctions don’t work, you escalate. If the child chooses to continue to misbehave, they climb the sanctions ladder until their time at your school disrupting the lessons of those who do want to behave (implying that some simply don’t want to) is ended prematurely.

It’s their fault, their choice.

But what if the behaviour is not as simple as cool, rational premeditation? What if that choice is the result of multiple influences that a simple sanction might not fix or deter? What if you, as the teacher, failed to see something that could have improved the situation because you believe that all you need is sanctions?

Seductive simplicity

This isn’t a theoretical exercise. This is me, armed with knowledge, underpinned by psychology, hard-won from improving behaviour in a school with my team, ringing the alarm: children don’t simply choose to misbehave, and using a system that ignores this means we are failing vulnerable pupils.

Cast-iron behaviour policies - inflexible and easily interpreted - are alluring, I won’t deny that. They feel supportive, and for many children they work. Or at least they seem to.

Almost all behaviour policies I see rely on the pop-behaviourist principles of reward and punishment to do their heavy lifting. It’s basic gain-or-avoid tactics: compliance is motivated by offering a reward; noncompliance is deterred by threat of sanction.

This approach is seductive in its simplicity, and it places the reasons for behavioural difficulties and the responsibility for changing with the child. The school and teachers set out their rules and the children choose to fit in (or choose not to).

Many who work in schools will say that, when run properly, this system works: most children comply. The pupils know where the boundaries are, and the vast majority keep to the right side of them.

I agree. Most children do comply. But have we educated them to do so, or have they simply been coerced into playing along? Do they maintain those behavioural standards at home, in wider society? Will they as adults? How many children don’t really need a behaviour policy at all because school is a relatively straightforward place for them to be successful?

I don’t believe that these systems result in long-lasting behavioural change or the ability to self-regulate and I would argue that children won’t put their heart and soul into their work if the only reason they’re doing it is to stay out of after-school detention.

And I know, from my experience working in the alternative provision sector, that systems such as this fail and reject our most vulnerable students - the ones who need us most of all. Rewards and sanctions don’t just fail to improve the behaviour of these students, it can make it worse.

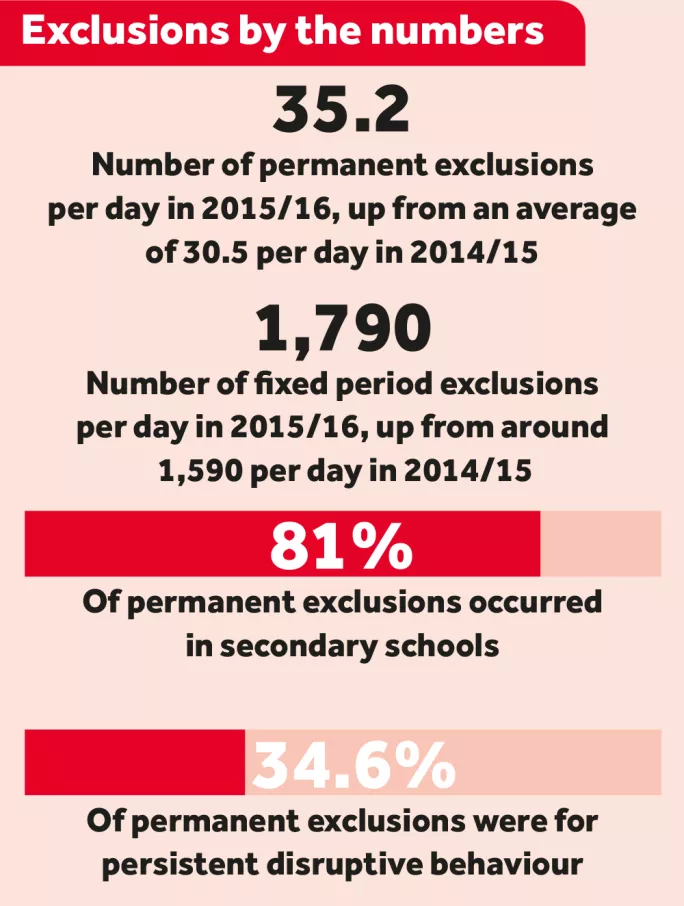

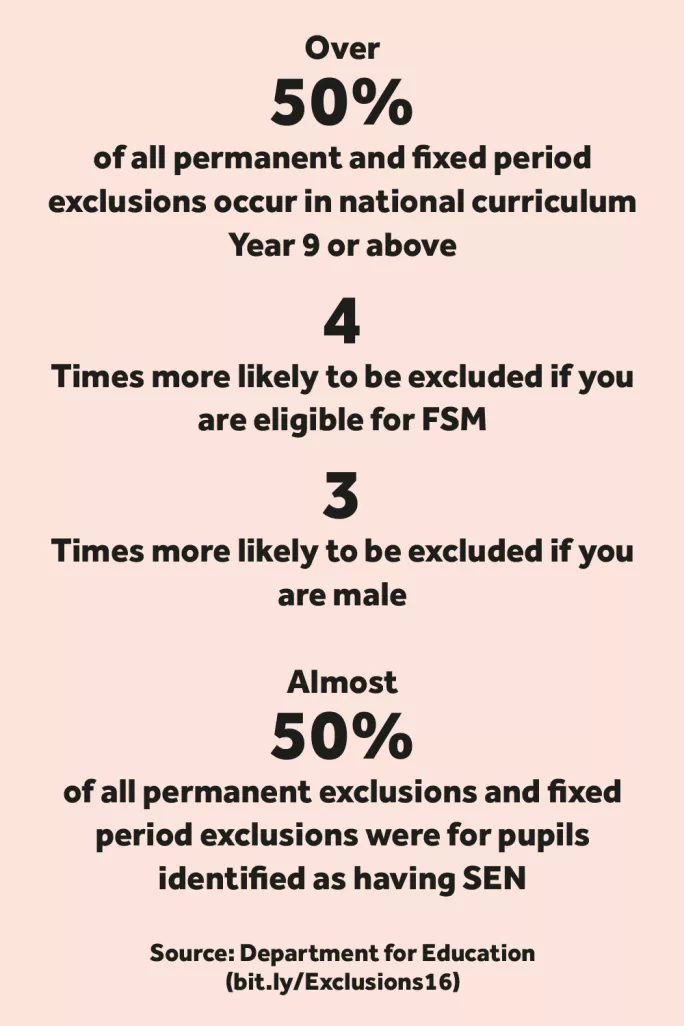

The system-wide data on exclusion is clear: the numbers of both permanent and fixed-term exclusions are rising year on year (and sharply recently). Some groups - most notably black Caribbean children and children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) - remain grossly overrepresented in the statistics. And that’s just the exclusions that we know about (see bit.ly/FloutingLaws and bit.ly/IllegalExclusion).

If these endemic behaviour policies were working, why would the statistics tell a different story?

If you stop to think about it, you know the answer because you will have seen how this works in schools: some children are earning rewards with ease while others seem to be endlessly pinballing from sanction to sanction with teachers despairing, “He never learns.”

You could argue that what is contributing to the problem is some permutation of the following: inconsistent application of policies by teachers, poor support from the senior leadership team and lack of availability of external agencies or funding.

Or it could be that the system and the thinking behind it is incomplete, which means that the children who need the most help are most likely to fall foul of it. It could be that our reductive way of viewing behaviour as a choice to be swayed through fear or coercion is deeply flawed. Psychology research suggests this is the case.

Here is the main problem: reward and punishment systems can limit a teacher’s ability to understand the behaviour of a child; this was certainly the case when I worked in a comprehensive. Such systems can lead you to overemphasise dispositional factors (essentially believing children are noncompliant because of innate aspects of their personality), and underestimate situational factors (the child’s environment, the people around them and the demands placed upon them).

In his 2015 book, Mindware, psychologist Richard Nisbett describes the importance of recognising the differences between dispositional and situational factors that affect behaviour: “[T]here is vastly more going on in our heads than we realise…Pay more attention to context. This will improve the odds that you’ll correctly identify situational factors that are influencing your behaviour and that of others…Realise that situational factors usually influence your behaviour and that of others more than they seem to, whereas dispositional factors are usually less influential than they seem.”

Overlooking details

So we could have decided that Amy’s behaviour in the situation described at the beginning of this article was because she is an attention seeker and that she would do anything to get it (how often have you heard “They’re just doing it for attention”?).

But we haven’t asked why Amy was seeking further control over the situation, nor have we identified the problem we think Amy is trying to solve by behaving in this way. For example, we may have underestimated the influence of her significant literacy difficulties on her thinking: the avoidance of work that looked threatening and the fact that risking a sanction may have been preferable, in her mind, to the inevitable failure and shame that would have followed had she given the work a go.

Children don’t always make simple choices and thus you cannot tackle their behaviour with simplistic solutions. The child in these situations is unlikely to be positively influenced by a sanction or a reward. Instead, the determining influences on the child’s decision to misbehave need to be explored by the teacher if they want lasting behavioural change. If they don’t do this, then the same behaviour is likely to reoccur because the situational factors persist.

How might this be done? Psychologist Ross Greene says that “children do well if they can”. He argues that if they are not doing well, then it is likely that their environment, including the people around them, is demanding skills that are underdeveloped in them - “they are lacking the skills not to be challenging”. This is a very powerful way of thinking.

I always remind colleagues that, in schools, “doing well” refers to the teacher’s definition of doing well. So for Amy, a fear that she couldn’t do the work that was required of her (success according to the teacher) meant that doing well involved doing whatever she could to avoid the work.

Greene’s approach to improving behaviour essentially amounts to solving problems by identifying those skills that are lagging. And this is where some teachers may become uncomfortable, because addressing the behaviour requires not just an understanding of the problems of the child, but it may also require your own behaviour as the teacher to change. In any situation there are two problems to solve, yours and the student’s - with yours almost inevitably being far easier to work out.

In Amy’s case, improving her behaviour using Greene’s approach could be as follows: the lagging skill could be identified as “difficulty managing emotional response to frustration so as to think rationally”.

This is influenced by her literacy difficulties as she deems the task to be impossible. The late arrival, swearing and disruption would be understood as secondary behaviours. Her fear of the comprehension exercise and her perceived lack of ability to attempt it, coupled with the risk of public embarrassment, would need to be supported so she could experience some early success and build some confidence and trust. Amy would then become less likely to engage in work avoidance next time.

Teachers are nervous of this approach. It takes time, leaves you feeling deskilled, irritated and worried you may be making allowances for badly behaved children. And it may feel unfair.

But let me try to persuade you. What sits neatly beside both Greene’s and Nisbett’s work is the concept of “unconditional positive regard”, which was developed by Carl Rogers (1902-87), a humanistic psychologist. A complete and unconditional acceptance of each child in your class, of who they are and what they do, is the bedrock of any work to improve behaviour. Without this, children are accepted only under certain conditions that you or the school get to decide - conditions that may well be unknown to the child - and this positive regard is withdrawn when the child behaves in ways that breach those conditions.

Unconditional positive regard means accepting that the child is attempting to deal with situations in their lives as best they can. Is the pupil’s behaviour inappropriate? Maybe. Is it destructive? Possibly. But you start from where the child is at and seek to improve from that position. You do not start by punishing them for not being where you want them to be. You do not keep them at arm’s length from the school community until they learn how to behave within. It’s an additive model, not a deficit one.

This categorically doesn’t mean that we allow children to do as they please, but it does mean that we don’t write them off or predict failure. It does mean we are forced to stop viewing behaviour as choices that can be improved through fear or praise.

You may see this approach as unworkable, but I have seen it work many times. I have used these theories as the basis to transform behaviour with my team in a school where I was headteacher. And when you start following this path you realise that reward and punishment is a glass hammer in your behaviour toolbox. It is one where the children who are vulnerable do not have their needs addressed and instead they end up in specialist provision.

We have not done our job when that happens. We spend more time with our pupils than any other professional and we build relationships with these children that are the strongest they are likely to have outside of their family. We are best placed to improve behaviour, and it is our duty to do so.

We are educators. Reward and punishment is about coercion; the methodology I have set out is about education. Behaviour is not simply a free choice, and we need to make the choice to recognise that.

Jarlath O’Brien works in special education in London. He tweets @JarlathOBrien

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters