‘Why must we label primary children as failures?’

You’re running a marathon. As you approach the halfway mark, you can see runners ahead being spurred on by people waving signs saying how well they’re doing.

Now it’s your turn. But as you puff past 13 miles, the spectators are booing and telling you that you’ve failed.

Still feeling good?

At Year 6, children have seven years of education behind them - and another seven to go. They’re facing their biggest challenge so far - the transition to secondary school.

But as they leave primary, schools must by law tell their parents whether they have met - or failed to meet - expectations.

“I think it’s a disgrace and a damning indictment of our education system that we do this to children,” says Rob Carpenter, chief executive of Inspire Partnership, which runs four primary schools in south-east London.

“No improving education system in the world labels children in the way we do.

“They are moving away from labels and we are still using them. It’s crazy and it does nothing to raise standards.”

Now the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) is calling for change.

In a wide-ranging review of primary accountability, it makes a number of recommendations aimed at making the system fairer for schools and better for children.

And one of them is that schools should no longer have to tell pupils that they have not met the expected standard; something they been forced to do since last year.

‘Potentially damaging’

At the end of primary, children take external tests in reading, maths and Spag (spelling, punctuation and grammar), and are assessed by their teachers on writing.

The results of these tests are reported to parents - and the ASCL thinks it is important that they are. What it thinks is “potentially damaging”, however, is the insistence, in law, that they are told if their children have not met expectations in any of the three external tests.

“We do think parents should be told their kids’ results. We think parents have a right to know and children have a right to know,” says Julie McCulloch, interim director of policy at ASCL and author of the review.

“But there is a big difference between being told you’ve got 96 marks on a test and being told you’ve not met the expected standard.

“That is not something we do to a child at any other stage of education, even at GCSE - if they get a grade 3, they’ve got something; they understand that within a broader context. But the starkness of the phrase ‘not met expectations’ is potentially damaging when kids are at a vulnerable point.

“However much schools play Sats down, kids know it is an important set of tests and then to be told they have not met the standard expected is really harsh and damaging.”

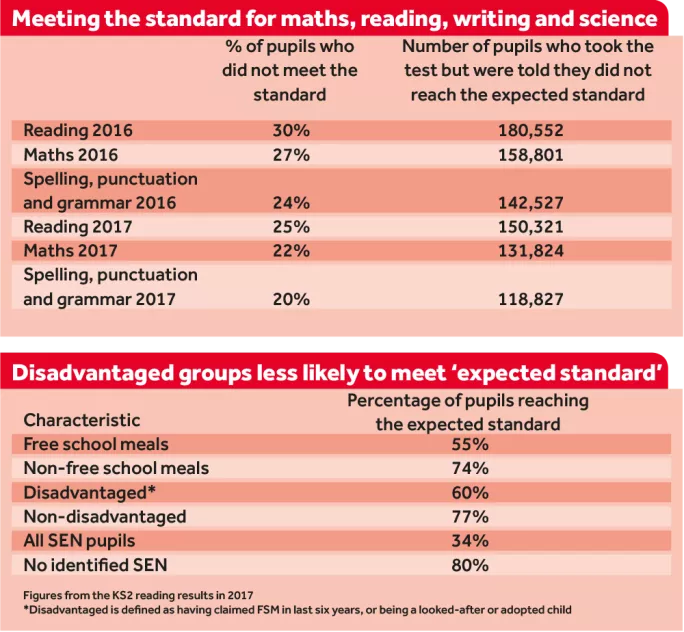

Last September, more than 150,000 pupils began secondary a few weeks after being informed that they had not met the expected standard in at least one of their Sats.

Some schools do their best to try and sugar the pill. “We discuss it at parents’ evenings, saying your child is on track or not on track, but we are much more positive about it,” says Laura Darley, assistant head and Year 6 teacher at Parklands Primary in Leeds.

“We say, ‘This is where you can go, this is what your child needs to develop.’ Because I would panic if I thought my child had not met expectations and that was the end of it.”

Parklands’ parents’ evenings are held in the first two terms of the year, letting parents know what progress their child has made and prepping them for the Sats to come.

But the letters to parents telling them their child’s Sats results, and whether they have met the expected standard, are sent alongside the child’s reports at the very end of Year 6. The results come back into school only a couple of weeks before the children leave.

“We have to send the results, legally,” Darley says. “But throughout the whole of Year 6 we do talk about Sats and how they are not the be all and end all of primary, and that rubs off on the kids.”

The legal requirement to tell parents a child’s Sats results is nothing new and has been in place since at least 2005. But the last two years have seen a change that has left many schools concerned about the impact it is having on children.

Until 2016, the old system of national curriculum levels of attainment was in place and parents were told something positive about their child’s achievements, even if they were lower than had been hoped for. The vast majority would have achieved a level.

“At least when school said, ‘You have achieved level 3,’ it focused on what you had achieved - it is psychologically different,” McCulloch says. “Now we are at the point where children have got to the end of seven years of primary education and this is the culmination of all that work. There is something about that phrase ‘not met expected standard’ that feels like it negates all the hard work children have put in.”

The problem goes back to 2013, when the government proposed changing the primary assessment system to reflect the new national curriculum.

Since the introduction of Sats in 1989, pupils had been assessed against an attainment score that initially consisted of 10 levels, and then, after the 1994 Dearing Review, eight levels. The national curriculum set out descriptions of what children needed to be able to do to reach each level, and teachers assessed pupils against these descriptions.

But in 2011, the expert panel asked to review the national curriculum recommended that levels be scrapped because they had little real meaning in terms of what pupils had learned. The government obliged and Sats results were last reported in terms of levels in 2015.

In 2013, a suggestion had been made that parents should be told which national 10 per cent band their pupil’s score finished in. Final government proposals in 2014 rejected this but simply said that a pupil’s results in reading, maths and Spag tests should be reported to parents as scaled scores.

Two years later, new Sats were introduced to match the new curriculum, in a process that was traumatic for all concerned, with leaked papers, repeated clarifications and a reading test later deemed “unduly hard” by Ofqual.

By September of 2016, the Commons Education Select Committee had begun an inquiry into the impact of the reforms on primary schools. And it was around this time that concerns about the reporting of the results and the effect this was likely to have on children began to surface.

Among the 389 pieces of written evidence submitted to the committee’s inquiry, the growing anxieties were there for anyone willing to look.

“How must it feel, as a child, to be told that they have not met the ‘expected standard’, rather than praising them for the progress they have made?” the primary association of St Helens’ Headteachers asked.

Wednesbury Oak Academy, in the West Midlands, wrote: “A child who has scored under 100 (sometimes only by a point) is regarded as not achieving the national average. There is no measure of success for these children.”

Henley Primary School, in Ipswich, was also concerned about “the impact of this pass/fail assessment” of pupils.

“Do the committee seriously consider pupils at 7 and 11 old enough to shrug off the label they have given when, in many cases, it is clearly a false label?” the school wrote in its submission to MPs. “How motivated will these pupils be as they move on to the next stage of their learning?”

Maybe these genuine concerns about the impact that a new “cliff-edge” verdict would have on 11-year-olds were drowned out by wider problems with the new Sats. Or maybe they were just ignored.

But when the reporting requirements for Sats in 2017 were announced, the necessity for schools to tell parents whether their child had met the “expected standard” was made explicit.

And in July, as Year 6 children all over England began to set their sights on secondary school, more than 150,000 of them had letters sent to their parents saying they had failed to meet expectations.

“It makes them feel like a failure - that score doesn’t show how much progress they’ve made,” says Chris Dyson, head of Parklands Primary in Leeds.

For critics, what makes the current situation even more concerning is the kind of pupils who are affected. Children claiming free school meals are roughly twice as likely to fall below the expected standard in reading than their wealthier classmates.

And Carpenter, who as a former head has been at the sharp end, worries that giving any parents this news may only make the situation worse. “We talk a lot about how to build confidence for children at school, but what damage is this doing to children via their parents?,” he says. “Parents see the label, not the journey.

“Parents tend to put more pressure on their children. Parents tend to see performance in terms of test scores, rather than progress.

“Children carry that badge with them into their secondary school and there is a high likelihood that it will impact their success later in life. I don’t agree with that.”

But couldn’t being told that they have failed actually spur children on to success? There are plenty of examples of people who used early setbacks to drive them to achieve in later life.

“There are some people for whom that sort of categorisation ups their motivation,” says Daniel O’Hare, a chartered educational psychologist from the British Psychological Society. “If you come from a home where you go to libraries and have access to a range of cultural activities, then it is not necessarily the case that a label would possibly do you harm.

“But where you have children with a low level of resilience, who have family backgrounds where education is not valued, those labels can have a hugely detrimental effect.

“The idea of saying to a child at the end of seven years of primary school, ‘You have not met the required standard’ - is that promoting psychological wellbeing? No, not at all.”

He points out that this is not how adults expect to be treated.

“Adults who are going through difficulties at work would be supported by their line manager or supervisor,” O’Hare says. “The approach would be to build on their strengths. You certainly wouldn’t expect to just get a letter on your desk saying that you are not meeting the expected standard.”

And yet this blunt approach is deemed entirely appropriate for tens of thousands of children, including some of the most vulnerable children in our society.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters