Why Pisa changes may make its results incomparable

The man running the world’s most influential education study has admitted that seemingly dramatic changes in performance for top-ranked countries shown by its “comparable data” could, in fact, be explained by changes to the way its tests are delivered.

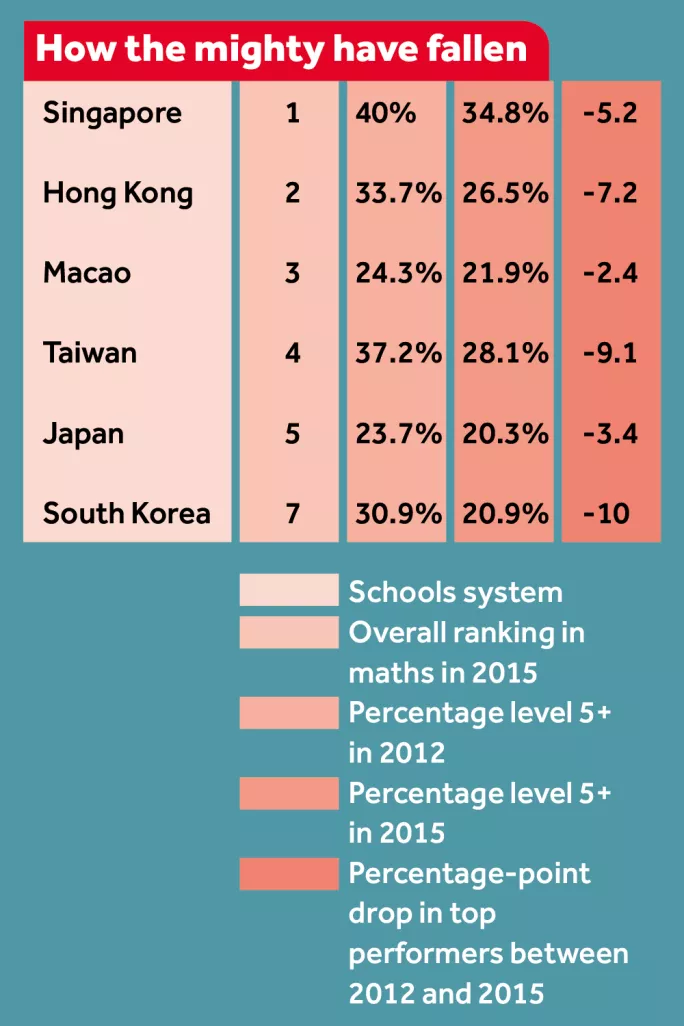

According to the latest Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) study from 2015, the global top-ranked performers in maths have all seen falls in the percentage of their pupils achieving high test scores in the subject over the previous three years.

That apparent decline in the ability of East Asian maths superpowers to stretch the brightest could have wider implications. Schools in the US and the UK have invested heavily in emulating the Asian maths “mastery” approach.

But now Andreas Schleicher, the official in charge of Pisa, has said that this fall may not be due to a drop in the performance of these Asian powerhouses. He said he was looking into whether the decline could be explained by the fact that Pisa used computers for the main tests for the first time in 2015.

In other words, data that is clearly presented as “comparable” in the study may not be comparable at all.

The admission has led critics to question the whole reliability of Pisa and to call for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which runs the study, to be more open about its limitations.

According to the 2015 Pisa study, all six of the top-ranked systems in maths with comparable data saw falls in the percentages of their pupils with top levels of attainment in the subject, compared with the previous 2012 study.

Tigers cut down

South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong experienced respective declines of 10, 9 and 7 percentage points in the proportions of students with the ability to select and evaluate appropriate strategies for complex problems. Singapore, Japan and Macao also saw drops.

China, the other top-ranked performer in maths, had no comparable data as it entered only as Shanghai in 2012.

When asked why he thought these education superpowers had all dropped in performance, Mr Schleicher admitted they might not have done so at all. The OECD education director suggested that the move to computer-based tests might be the reason.

“Further analysis is needed to establish the causes of decline in the share of top performers in some of the highest-performing countries,” he said.

He said although the study had ensured that, “on average”, pupils taking paper- and computer-based tests scored the same, that might not be true for some groups of high-performing pupils.

“It remains possible that a particular group of students - such as students scoring [high marks] in mathematics on paper in Korea and Hong Kong - found it more difficult than [students with the same marks] in the remaining countries to perform at the same level on the computer-delivered tasks,” he said.

“Such country-by-mode differences require further investigation - to understand whether they reflect differences in computer familiarity, or different effort put into a paper test compared to a computer test.”

But there is no mention of that possibility alongside the data in the report showing the change in the percentage of top-performing students between 2012 and 2015. The report clearly says the data is “comparable”.

The possibility that the change to computer tests could have made a general difference is covered elsewhere in the study, but then largely discounted.

‘Reliability’ questioned

Pasi Sahlberg, an expert in global education reform, said that Mr Schleicher’s admission could have wider implications.

“It raises new questions about the reliability of the [Pisa] test itself,” he said. “Students’ measured literacies in reading, mathematics and science should not depend on how they are measured, if the scope of testing remains the same.”

John Bangs, chair of the OECD’s trade union advisory working group on education, said: “Minor changes to the operation of the tests can lead to major implications because governments and the media are obsessed with the rankings on the performance tables.

“It shows the absurdity of looking at rankings on a crude performance table,” he added.

Yong Zhao, professor of education at the University of Kansas, agreed. “What the OECD should really do, as a first step, is to stop the fanfare and sensation-grabbing activities about its results,” he said.

“Instead, it should talk more about the limitations and issue cautions against drawing broad conclusions from the results.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters