Why is primary science dying?

It was a week that showcased the excitement and wonder of science: handmade rockets soaring into the sky, static electricity making people’s hair stand on end and cornflour transformed into amazing pink goo.

But for all the photos and videos flooding social media showing primary schools celebrating British Science Week, which drew to a close on Sunday, the hard truth is that in too many schools it is a subject that is being sidelined. Indeed, for some trainee primary teachers, science feels like a “dying field”.

One, having completed a year’s training in which science seemed to be an afterthought, questioned whether even the content she did learn would help her in the classroom.

“I don’t know if I would actually really be able to use a lot of the information I was taught [in my training], other than some of the fun activities,” she reflects ruefully.

By the government’s own reckoning, it shouldn’t be this way.

If ministerial speeches and policy announcements are to be believed, Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects are vital to the success of post-Brexit Britain. Last year’s Conservative manifesto emphasised how “our long-term prosperity depends upon science, technology and innovation”.

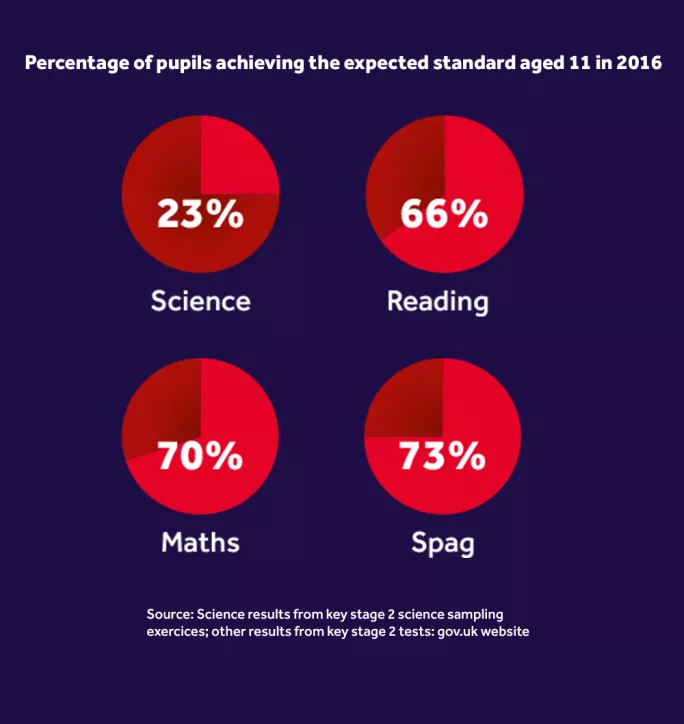

But when the government last monitored the national performance of 11-year-olds in science two years ago, it found that less than a quarter - 23 per cent - had achieved the expected standard.

As a country, we devote less time to primary science than similar nations, and many of our primary school teachers leave their teacher training courses feeling ill-equipped to teach and assess science.

It is a problem with many causes, from a system of testing and inspection that puts a premium on English and maths, to teacher training courses that squeeze out science, and a funding crisis that penalises a subject that can require expensive equipment.

The government may stress the importance of science for our future. But this is not reflected in the experience of many children in primary schools, where the impressions they form will influence their subject choices and career options in the years to come.

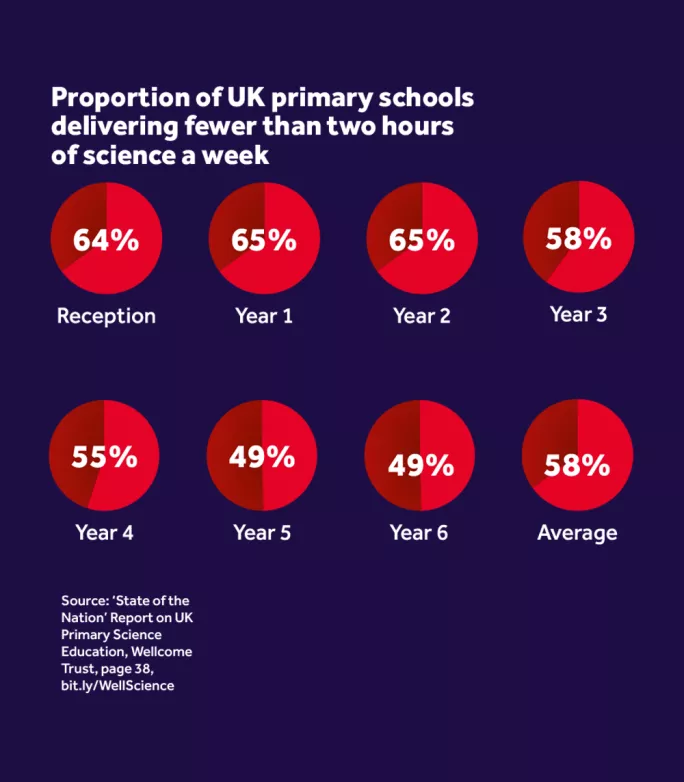

Research by the Wellcome Trust found that the UK spends less time on primary science that its international competitors, with an average of one hour 24 minutes a week, compared with two hours in other, similar countries. The Association for Science Education (ASE) knows of primaries where the figure is as low as 30 minutes.

“As people even said in the training, it seems to be like a dying field,” one NQT says. “You have to have people who champion it. People try to champion it, but it’s not given enough time.”

Some new teachers start their primary school careers raring to enthuse their pupils about science, but they find themselves stymied as soon as they start.

“I felt really confident,” says another NQT, “but then you hit the stark reality of when you get into school and, ‘Oh no, they don’t have thermometers.’ The [training] days were really great, but putting it all into practice when you have got schools with tight budgets was a lot harder.”

Hilary Leevers, head of education and learning at the Wellcome Trust, believes funding is “both a real and a perceived barrier”. “There will be some instances where it truly is a struggle, but it is also possible to work your way around it,” she says. For her, teachers who go on CPD courses can learn how to do science “on the cheap” and discover opportunities to share or borrow pieces of equipment.

However, CPD is another area of concern: 30 per cent of teachers surveyed by the Wellcome Trust said they had “not received any support for science teaching in the last year from my school”.

The trust’s report, published in September, suggests that across the UK 83 per cent of teachers thought English was “very important” to their school’s senior leaders, and 84 per cent thought the same for maths. But when it came to science, the figure was a mere 30 per cent.

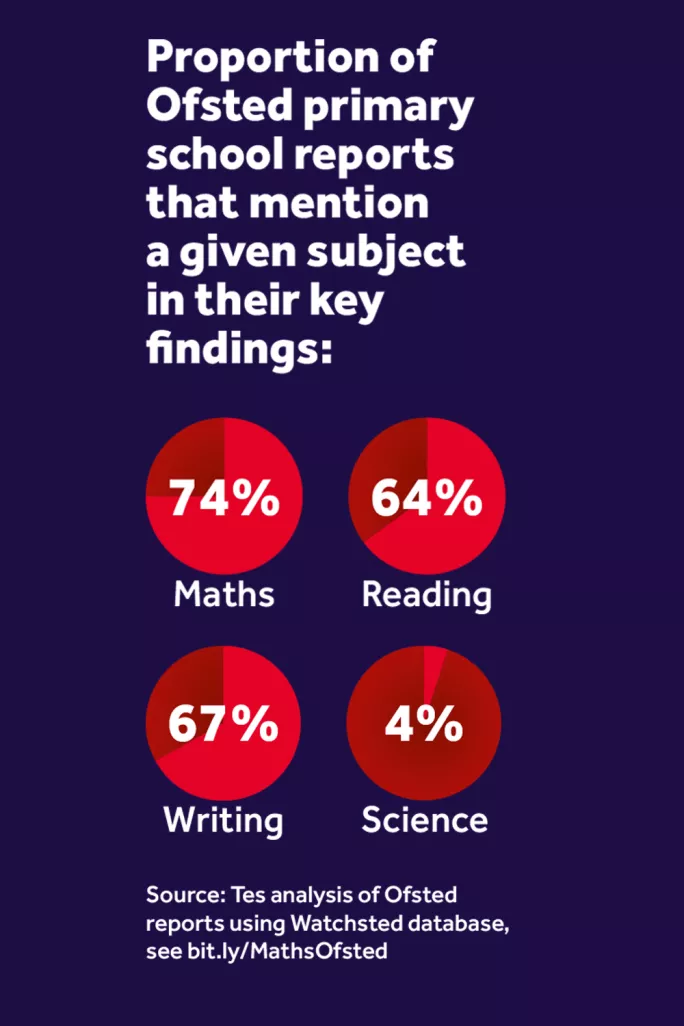

And Ofsted does not appear to incentivise schools to prioritise science.

In October, a Tes analysis found that maths was mentioned in the key findings of 74 per cent of primary Ofsted reports, and writing in 67 per cent. By contrast, science appeared in the same way in only 4 per cent of reports.

Marianne Cutler, the ASE’s director of curriculum innovation, says that “very often the message [from inspectors] was, ‘We don’t really care about your science because we have come to look at other things, particularly your English and maths, and we are very likely not to talk about science.’”

It is an issue that the ASE took up with the inspectorate two years ago, urging inspectors to ask about science when visiting primary schools, and Cutler suggests there has been some improvement since.

Assessment is another area of concern for the association, with Cutler warning that there is a “large variability” in how confident primary teachers are in assessing their pupils in science. “Teachers are not always now able to really know where their pupils are within primary science,” she says.

For her, there is a need for professional development to help with moderation, including exemplars of good practice for the subject at different stages. She recommends the “pyramid tool” developed by the Teacher Assessment in Primary Science project at Bath Spa University.

So, with these challenges facing science in primary, how well are pupils able to perform?

Every two years, the Department for Education conducts a sampling exercise involving thousands of 11-year-olds in hundreds of schools. The aim is “to monitor national performance in science”.

It last did this in 2016, when 23 per cent achieved the expected standard - a fall from the 28 per cent in 2014, although the latter sampling was carried out under a previous curriculum. Comparisons with other subjects are hard because of different methodologies used, but in 2016’s key stage 2 tests, 66 per cent of 11-year-olds reached the expected standard in reading, and 70 per cent in maths.

But when teacher assessments, rather than sampling or externally marked tests, are used, 81 per cent of pupils reached the expected standard in science, on a par with reading at 80 per cent and maths at 78 per cent.

As with so much in England’s school system, accountability is at the root of much of what is currently happening with primary science.

For primary schools, two subjects are king: English and maths. Data in these two areas decide whether a school meets the floor standard, whether it is “coasting” and whether it is towards the top or the bottom of the league tables. Performance in the three Rs will decide the future of a school, and its senior leaders.

For Michael Reiss, professor of science education at UCL’s Institute of Education, the emphasis on English and maths in Sats “massively” affects the place of science in primary schools. “The UK has a very strong tradition in primary science, with a commitment from classroom teachers to teaching science, generally quite good facilities and a tradition of science inquiry,” he says. “However, since science became one of the three core subjects in the national curriculum back in 1989, one of the disappointments has been the reduction in the time spent learning science, as schools have had to respond to an overemphasis on testing in English and mathematics.”

It is a view echoed by Leevers, who believes that the subject has experienced “a few years of decline, particularly in response to the removal of the primary science Sat”.

That happened in 2009. The Labour government scrapped the test amid concerns that it encouraged teaching to the test, rather than real-life science.

At the time, heads’ leaders warned that scrapping the science Sat would “narrow the curriculum even more” - although few today believe that reinstating a new high-stakes science test is the solution.

Recent Ofsted research on the curriculum corroborated this concern, with chief inspector Amanda Spielman telling January’s ASE conference that “in primary, there is a continued narrowing of the curriculum where schools’ understandable desire to ace the English and maths Sats has been squeezing the science curriculum out”.

But despite all the challenges, there could be some cause for optimism. Far from pushing out science, some believe that the focus on literacy could, in fact, be the key to pupils succeeding in the subject.

A report from the Education Endowment Foundation and Royal Society last year found that the strongest factor affecting pupils’ science scores was how well they understood written texts.

But even here, Leevers strikes a note of caution, warning that as science is mostly assessed using pen-and-paper tests, it is no wonder that children with good literacy skills perform well. The question of how to assess science is, she says, “an issue we have throughout the education system”, and The Wellcome Trust is now funding research into ways of assessing other elements of scientific knowledge, understanding and skills.

As for Ofsted, Spielman told science educators that it will be “looking in depth at science curriculum in primary” in the second part of its research into school curricula, which “will feed into the way we address curriculum in the new inspection framework for 2019”.

For the DfE, science is “an important subject” that all primary school children are required to study.

A spokesperson says: “We have a new more rigorous science curriculum and have backed that with £12 million of investment to establish a national network to share best practice among teachers. We have also provided a further £10 million for bursaries for science teachers to continue on-the-job training and development.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters