Will artificial intelligence ever transform our schools?

Every day, children arrive at school and receive their personalised schedule of what they will learn. The programme is determined not by a teacher, but by an algorithm.

They might be learning in a class with a teacher or with classmates only. Or they could be on their own with a computer, or online with a tutor. The computer decides.

And after each 90-minute lesson, they take a quiz to see what they know, which the computer uses to decide what and how they will learn tomorrow.

This isn’t a dystopian future, this is Teach to One: a middle-school maths programme operating in six schools in Manhattan, New York.

But on this side of the Atlantic, the edtech revolution that would transform our schools is like tomorrow: something we always feel is imminent, but that never arrives.

This is not to deny that tech has played an increasingly important part in school life for a number of years - just think of interactive whiteboards and management information systems - but it has largely been a case of evolution, not revolution: helping schools do what they have always done rather than fundamentally changing what they do.

Believe the hype?

If truly transformative technology were to arrive in schools in England, how would this actually manifest itself?

In America, charter schools - the equivalent of free schools - are most closely associated with artificial-intelligence assisted approaches, such as blended learning, in which pupils are taught by a mixture of machines and humans. Some believe it will take a new, trailblazing free school to inject the jolt of a new technology-based model of teaching into the English educational bloodstream. And if it worked, more would inevitably follow.

Others take into account the high costs associated with new technology and believe that, in England’s fragmented school system, only the large academy trusts would have the necessary resources.

High-performing academy chain Ark originally intended to introduce blended learning when it was first envisioning the creation of Ark Pioneer Academy in Barnet, but it has since backed away from the plans and now says the school will be more traditional.

So academy trusts might not yet be ready to take the risk. But the trigger for change could avoid the need for major top-down decisions and expensive overhauls of IT systems altogether. And it could come quicker than you think. Rose Luckin, an expert in AI and education at University College London’s Institute of Education, outlines a scenario in which, far from requiring huge new investment from schools, technology that would transform teaching would simply make use of the existing software and computers that the likes of Google and Microsoft are already putting into schools.

“It may be that things that are not explicitly designed to support teaching and learning are a huge part of the infrastructure,” she says, “and then if those organisations also start introducing more and more things, then the way in which those things are taken up could be quicker because the infrastructure is already there and is already being used.”

A former school teacher, Luckin can see a great prize in the grasp of AI. “It would be that increased ability to be a more effective educator because I’ve got information that I’ve just never had access to before that helps me understand my students’ needs more effectively,” she says. “A good AI system can also help me to develop knowledge and understanding in my learners by tutoring them in a very individualised way with particular parts of the curriculum.”

But she is no naïve, starry-eyed optimist, and can see a darker future for AI in schools if teachers and wider society were not involved in shaping the technology. Others simply do not buy the hype.

For Joe Nutt, an international education consultant who spent almost 20 years as a teacher, “we’ve not even taken the first steps” into a world of tech-enabled personalised learning. “You have to reject AI hype as the marketing hype it is,” he says.

Still, the transformative power of technology in education is something that is being taken seriously by some serious people.

The House of Lords has a select committee dedicated to AI. The Commons Education Select Committee has issued a call for evidence about “the impact of the fourth industrial revolution on the delivery of teaching and learning in schools and colleges”, and when members of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference gathered at the British Library for its spring conference, the theme was “artificial intelligence and virtual reality in education”. But schools could be late to the party.

In transport, Uber has upended the world of taxis. In retail, Amazon is threatening the high street. And in news, Facebook and the web are calling the future of print journalism into question. But if a teacher from the Victorian era walked into a 21st-century classroom, the chances are that they would be familiar with most of what they saw.

Why has education, a sector whose core purpose is to prepare young people for the future, been the slowest to make use of the new technologies that are transforming the world? Answers often focus on schools themselves, with suggestions that they are conservative and traditionalist; risk-averse and resistant to change. But while edtech consultant Henry Warren agrees with this assertion, he also points to the other side of the equation: the failure of edtech companies to create transformative products that are irresistible to schools.

Education is, he says, “highly, highly fragmented. It’s a hard space to make money in.” He contrasts the sector with the video-games industry, where he says a $260 million (£192m) investment in the creation of Grand Theft Auto V in 2013 was justified by the $1 billion (£739m) it reaped within the 72 hours of its launch. Why? Because it was a single product that could be sold in markets around the world.

“You just don’t have that [equivalent] in the education space,” says Warren. “It’s really difficult to take a product and port it between different markets, and then when you add in how complex the sales cycle is selling into schools, it’s kind of hard to justify spending half a billion dollars on a product.

“If you take how complex education itself is - educating kids is really hard, and you are not educating a child, you are educating lots of different children, all with different abilities - then your software is going to have to cope with that. And to do that you need to be able to write some fairly big cheques to do complex things in terms of software.”

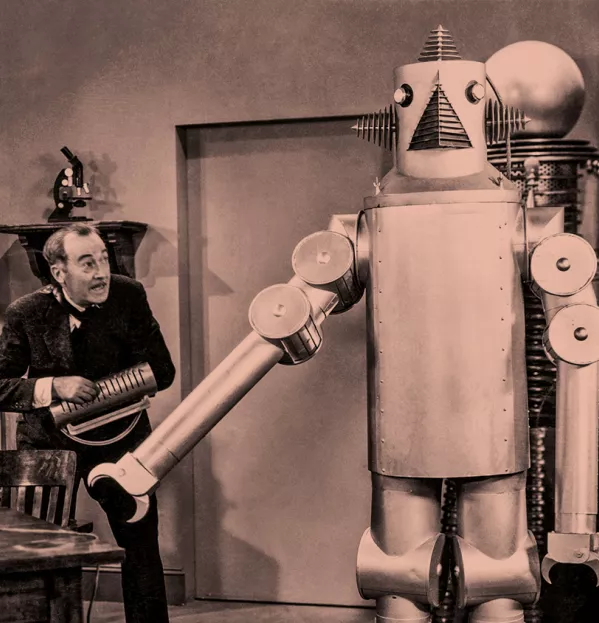

This is not to say that the technology does not exist. But AI is unlikely to translate into what scientist and broadcaster Kat Arney has called the “bizarre dystopia of the robot at the front of the class teaching the lesson”. She has said that she would be prepared to bet money on this scenario never happening.

No replacement for good teachers

Technology is already bringing a different model of schooling to some parts of the developing world, to deliver education in areas in which teachers are either poorly trained, or where none exist.

Bridge International Academies is the best-known and most controversial example. Its teachers deliver heavily scripted lessons from tablet devices, which send data back to America where it is analysed to assess both the teacher and their pupils.

Warren says this technology is not being used in England because, while the service offers a better alternative to a bad teacher, it is not better than a good teacher - and England has plenty of those.

However, some people believe a current set of circumstances in the English education system could provide an opening for transformative edtech to emerge.

One is the workload crisis. Education secretary Damian Hinds, who has made it a priority to address the growing burden on teachers, has spoken positively about the role of edtech in tackling the issue.

Another is the teacher-recruitment crisis. Last month, Tes reported that England would need to find tens of thousands of extra teachers by 2024 to cope with the projected rise in pupil numbers (“Where will we find a further 47,000 secondary teachers?”, 6 April). It is a task that Geoff Barton, general secretary of Association of School and College Leaders, called “Herculean”, and one that Warren believes will force schools to turn to technology to teach children.

Then there is the financial squeeze facing school budgets. Again, Warren believes this will give schools no option but to use technology to transmit information to pupils, with the humans in the room providing pastoral care - roles that are cheaper to fill than qualified-teacher positions. And if a developing country that is relying on edtech shoots up in the Programme for International Student Assessment rankings, it could force the issue onto the ministerial agenda.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters