And I’d like to thank.

A big poster of Olympic gold medallist Jessica Ennis hangs in the gym at her former school, King Ecgbert in Sheffield. It was put there not only to inspire the next generation of pupils, but also to show the pride of staff who worked with the athlete.

Teachers helped to spot and hone the talents of many of the sports stars who have kept Britain enthralled and entranced this week, with their staggering displays in events including athletics, cycling, rowing and swimming. From encouragement and advice to practical help, these teachers played a central role in their pupils’ journeys from school playing fields to Olympic glory. Many have been in the stands watching their former pupils succeed on the international stage.

Yet the arguments about the quality of physical education in state schools persist. This week, culture secretary Jeremy Hunt said some school sport provision was “patchy” and called for more investment in sport at primary- school level.

Lord Moynihan, chair of the British Olympic Association, has urged the government to increase sport funding. The peer, a former sports minister under Margaret Thatcher, said school sport policy was “bureaucratic” and needed more money to fund a major expansion.

“There is a need for radical reform and I am calling for more money,” Lord Moynihan said. “There needs to be a total commitment to ensuring a sports participation legacy that has to focus on schools and clubs.

“For seven years, successive governments have been treading water. We have tens of thousands of kids watching great moments, which will live with them forever. The government should step up to the mark.”

As well as the focus on improving participation in the 14-24 age group, primary schools should be given help to provide more sporting opportunities, Lord Moynihan added.

But school sport has produced much for us to celebrate this summer. With just two days to go until the closing ceremony of the London Olympics, TES has spoken to the PE teachers of three of Team GB’s most high-profile champions - Mo Farah, Bradley Wiggins and Jessica Ennis - to find out the role they played on the path to glory and to discover their views on the current state of school sport.

Athlete - Mo Farah

Sport - Distance running

Teacher - Alan Watkinson

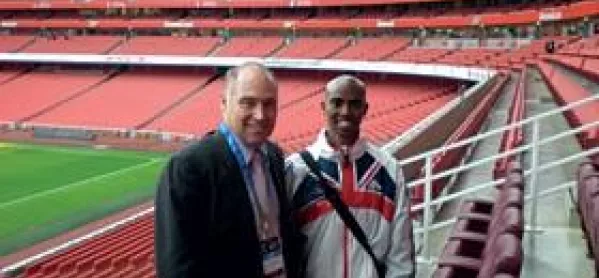

The nation will be watching tomorrow as Mo Farah lines up in his bid for a second Olympic gold medal, this time in the men’s 5,000m. None will be watching more closely than former PE teacher Alan Watkinson, who is such good friends with the athlete that he was best man at Farah’s wedding. Despite their close relationship, the 10,000m champion still calls Mr Watkinson “Sir”.

“It’s ridiculous now he is 29 and an Olympic champion, but he is something else,” said Mr Watkinson, who was in the stands on “super Saturday” to watch Farah take gold. “I have an enormous amount of respect for him and he still shows me respect.”

Farah’s life was transformed by the PE teacher, who spotted that he had the stamina needed to be a distance runner. The young Farah moved to London from Somalia aged 8 after the country sank into civil war. At 11, he found himself in Mr Watkinson’s PE class at Feltham Community College, west London. His English was “atrocious” and his struggle with the language was holding him back academically.

But all this changed when Mr Watkinson witnessed him on the football pitch. Soon Farah was winning school and national cross-country titles. His English quickly improved, too.

“He loved sport so much and it was a relief to him - sport meant he was on a level playing field with other pupils for the first time,” said Mr Watkinson, who now runs the School Sport Partnership in Hounslow, west London.

“It meant he was shown respect from other teachers and pupils. When Mo struggled to speak English he did mess around in lessons. Sporting success gave him self-esteem; he was seen in a different light. He got on with everybody and was well liked. Like now, he was gregarious and fun loving.”

Mr Watkinson helped Farah practically, driving him to competitions and getting him travel permits to go abroad for training. After leaving Feltham, he studied at Isleworth and Syon School for Boys, also in west London, where Mr Watkinson had also moved to teach.

Mr Watkinson feels strongly that there are good opportunities for pupils with extraordinary sporting talent to thrive in state schools. “Children are mentored, they get extra support and this should be more widely recognised,” he said.

“We can bring these pupils through the state system. But the powers that be could make it an easier process for us and we need to give more support to primary school teachers to teach good PE lessons. They can be good at it, but they often lack confidence, training and knowledge.”

Mr Watkinson hopes Farah will go to Hounslow to meet pupils before he returns to the US, where he trains. But for now he is still reliving the “incredible experience” of seeing the pupil once reluctant to exchange football games for cross-country competitions become the toast of London 2012.

Athlete - Bradley Wiggins

Sport - Cycling

Teacher - Graham Hatch

Graham Hatch, who taught Bradley Wiggins PE at St Augustine’s CE High School in Kilburn, north London, has watched his former pupil make history twice this year, first by winning the Tour de France and then an Olympic gold medal in the time trial.

Long before his current success, Wiggins had acknowledged the support and encouragement that Mr Hatch gave him. In an interview with TES two years ago, Wiggins said: “When I told most other teachers that I wanted to win an Olympic gold in cycling, they dismissed it as crazy. They said: `How many inner-city kids do that?’

“Mr Hatch was different. He took an interest, asked me about my cycling and generally encouraged me. I think he and my mum recognised that there were worse things I could have been involved in, like messing around with the rough kids on my estate.”

Mr Hatch remembers a boy who loved sport and could not wait to leave school. “Cycling was becoming his life; he wasn’t too bothered about the academic side of things,” he told TES this week. “Bradley was very down to earth. He had a great sense of humour. You had to take him to task sometimes and ask him to sit down and stop talking. He didn’t push himself hard in lessons; he was very capable, but his desire was for sport.

“I took an interest in how his cycling was going and when his competitions were, and I think he appreciated that.”

Wiggins left St Augustine’s after taking his GCSEs in 1996 and quickly became a professional cyclist, but his family are still very much involved in school life. His brother Ryan was a learning support assistant at St Augustine’s until this summer and his mother Linda worked in the school office before moving to a similar job in a nearby primary.

“Ryan helped in my GCSE PE theory lessons and we used to talk about Bradley and use him as an example a lot: his nutrition and heart rate,” said Mr Hatch, who has worked at the school since 1978 and is now assistant headteacher. “Ryan gave the class an insight into his schedule and the discipline needed to perform at that level.”

Mr Hatch believes better links between sports clubs and schools would help talented children such as Wiggins who face difficulty finding facilities in inner cities.

After he won his first Olympic medal 12 years ago, Wiggins returned to St Augustine’s to present Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards. Appropriately enough, the school’s motto is now “Be the best you can be”.

Athlete - Jessica Ennis

Sport - Heptathlon

Teacher - Chris Eccles

School athletic records set by Jessica Ennis at King Ecgbert School, Sheffield, still stand. Her natural ability was evident, but PE teacher Chris Eccles said she never boasted about her achievements. “Jessica was very modest, but we celebrated her success on a regular basis,” he said.

PE teachers kept a picture of Ennis in the staffroom that demonstrated how unique she was. Aged 12, she is standing in front of a high jump bar that is taller than her; the photograph celebrates the first time she jumped a height of 1.56m.

“From this moment on, we could be reasonably confident that this was someone with a little bit of talent,” Mr Eccles joked. “Jessica’s achievements were partly why we established the school records in 1999. In Year 7, when she recorded a high jump height of 1.56m in a city championship, I thought `Good grief’. By Year 9, this was 1.71m.

“Jessica did A-level PE, for which you usually have to submit video evidence for the practical part of the course. I decided just to write a letter saying she had just come back from the World Youth Championships and had got fifth place, and all her scores could be checked online.

“I never got a reply to say that was OK, but she got an A.”

Mr Eccles, who now works at Dinnington Comprehensive in Rotherham, saw Ennis compete at the Olympic Stadium last week after spending hours online trying to get tickets. He sent a congratulatory text message and received a reply from his former pupil, who said she felt like “the happiest girl in the world”.

“I remember going with Jessica to collect her first vest when she represented England. It was so emotional seeing her start to compete at such a high level. I have an incredible sense of pride seeing her achievements now; it is overwhelming,” Mr Eccles said.

After her GCSEs, Ennis achieved A levels in English, psychology and PE before going on to the University of Sheffield. She graduated with a psychology degree, despite winning a bronze medal at the Commonwealth Games halfway through her course.

Mr Eccles believes there should be better quality PE teaching in primary schools to ensure the London 2012 Games have a lasting legacy. “In primary schools, PE lessons often play second or even fourth or fifth fiddle to literacy and science. If you want to produce physically literate young people you need to teach them motor skills such as throwing and catching early on,” he said.

“People like Jessica, Bradley Wiggins and Mo Farah were completely inspired as young people and their legacy will inspire thousands of other children. So there must be high-quality PE lessons in primary schools.

“It’s not just about producing the next Olympic gold medal winner. It’s about getting children confident and engaged.”

DfE `trusts’ teachers and parents to deliver enough sport

Headlines were generated this week with stories that the government had scrapped a target for schools to provide two hours a week of PE. But the rules governing how much PE schools are supposed to offer and how they prove it have not changed since October 2010.

At that time, education secretary Michael Gove scrapped the annual school sport survey, which collected information about the number of children engaging in physical activity and the kinds of sport they were playing.

He also ended the target of five hours of sport a week - two hours in school and three hours out of school - that had been introduced by the previous Labour government. Instead, the coalition government said it “expected” schools to provide the same two hours a week of PE and sport, although without the survey it would not be able to hold them to account.

“Instead of handing down targets and quotas from Whitehall, we have chosen to trust teachers and parents when it comes to deciding how much sport pupils should do,” a Department for Education spokeswoman said this week.

“We want to strip away the red tape that takes up too much time teachers should be using to teach, run sports clubs or plan lessons. In the past, schools were heavily over-burdened with paperwork and form-filling.”

But the Youth Sport Trust said the end of the PE survey in 2010 had caused problems. “Measuring the number of young people participating in two hours of school sport did give a clear indication of participation levels in sport in schools. Obviously, now this has been scrapped it is difficult to know exactly what the picture is across the country,” said chief executive John Steele.

Photo Mo Farah and teacher Alan Watkinson. Photo credit: Corbis

Original headline: Inspire a generation? Meet the teachers who did, all the way to gold

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters