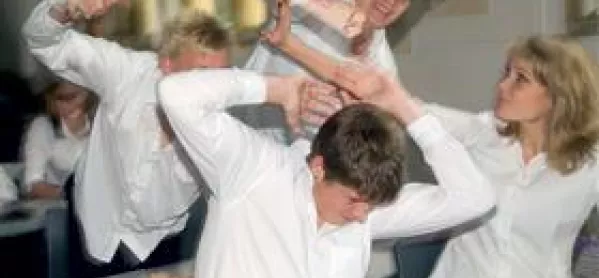

Dial 999, the students are playing up in class

A catalogue of issues, made worse by budget and staffing cuts, is affecting teachers’ ability to cope with bad pupil behaviour, new research suggests.

Early findings of a survey of teachers by the EIS teaching union indicate that inadequate assistance for pupils with additional support needs (ASN) is a major issue for behaviour management. Even experienced teachers report being reduced to tears by “constant disruption”, prompting calls for urgent measures to tackle the problem.

School policies that now make exclusions relatively rare should also be relaxed, some teachers told the EIS.

Yet despite respondents calling for the introduction of tough measures to combat the problem, including schools being more prepared to call the police in the worst cases, education directors hit back at the findings, insisting that pupils’ behaviour was “as good as it has ever been”.

One remedy suggested by union members is for the worst perpetrators to be punished by tending school grounds.

The declining number of educational psychologists is also cited as a crucial issue, with many teachers arguing that these professionals play a key role in helping pupils at risk of exclusion.

“With teacher numbers falling and class sizes rising, schools and teachers will face an ever-greater challenge in maintaining effective discipline in the classroom,” said EIS general secretary Larry Flanagan.

“That is bad news for staff, with indiscipline one of the key causes of stress for teachers, and bad news for the majority of pupils who are keen to learn.”

The initial findings by the union’s education committee are based on responses from EIS members in 21 of Scotland’s 32 local authorities, received in the first week of the research.

Although most pupils behaved well, Mr Flanagan identified a “persistent minority” who often failed to behave appropriately in classrooms. Persistent low-level problems - such as verbal abuse, misuse of mobile phones and refusal to follow instructions - were taking up “far too much” of teachers’ time, he said.

“Of particular concern is the situation where pupils who might be better placed in special schools are being mainstreamed, without the appropriate additional support being put in place,” Mr Flanagan added.

“I have heard first-hand from teachers faced with this situation and they have reported instances of experienced colleagues being reduced to tears trying to cope with the consequent disruption, which serves neither the needs of the individual child nor his or her peers.”

Serious misbehaviour such as physical assaults should prompt a call to the police, Mr Flanagan argued.

Meanwhile, one survey respondent said that serious offenders should be given jobs around the school or in the community, for example decorating the hall for Christmas or improving the appearance of the school grounds.

Overall, early responses suggest that most discipline policies are only “reasonably” effective or do not work at all. There is also a feeling among respondents that high-quality training on how to deal with misbehaviour is lacking.

John Stodter, general secretary of education directors’ organisation ADES, responded robustly. “Pupil behaviour in Scottish schools is probably as good as it has ever been, owing to the skills and confidence of teachers, the strength of school leadership and the rigour and consistency of behaviour policies,” he said.

But Sophie Pilgrim, director of Kindred, a charity that works with ASN children, warned that pressure on special school places was causing some pupils with complex requirements to be placed in mainstream education. The increasing number of children diagnosed with conditions such as autistic spectrum disorder, combined with declining teacher numbers, was putting a strain on mainstream schools, she said.

Speaking on behalf of the Scottish Children’s Services Coalition, Ms Pilgrim added: “This is not a matter of `indiscipline’ since children are not able to control behaviour which results from their condition.”

Scotland’s new Children and Young People Act grants educational psychologists a more central role in helping troubled pupils overcome behaviour problems, yet recent figures show a sharp drop in applications to the profession (“Support services - depressing times for psychologists”, 27 September 2013).

Carolyn Brown, chair of the Association of Scottish Principal Educational Psychologists, said: “There are significant worries about a general lack of capacity to respond to [these] increasing demands, thereby having a knock-on effect on teachers’ stress levels.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters