Arguments that the application of neuroscience could have a direct impact in the classroom are “a bit far-fetched”, according to new research.

Michael R Dougherty and Alison Robey, from the University of Maryland in the US, said that neuroscience was in fact “largely unnecessary for the development of effective learning interventions”.

“The idea that neuroscience can have a direct impact in the classroom is a bit far-fetched,” they said in a paper published this week.

“Neuroscience may be useful for understanding brain mechanisms and establishing connections to cognitive theory, but it is largely irrelevant to considerations of education policy and classroom practices.”

The pair cite the theory of “brain training” as a prime example of how “seemingly groundbreaking neuroscience findings…simply do not scale up to practical education interventions”.

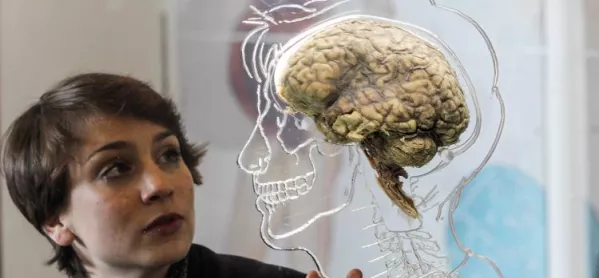

Educational neuroscience is a burgeoning field that brings together psychology, neuroscience and educational theory to explore how an understanding of brain mechanisms could lead to improvements in learning.

The discipline has been hailed as a way to transform educational practice through science, spawning initiatives such as London’s Centre for Educational Neuroscience, the Education and Neuroscience Initiative and the Neuroscience and Education Conference.

A teaching union also voted to train thousands of teachers in neuroscience to help them understand the mental processes behind learning.

But Professor Dougherty and Ms Robey said interventions based on cognitive theory, such as active learning and retrieval practice, have been far more successful in the classroom.

On this basis, they argued that funding should be geared more toward cognitive and social-psychology research, to create more evidence-based interventions in education.

They also argued that neuroscientists needed to dial down the hyperbole around their work to ensure the “public not be misled about the promise of basic research for addressing applied problems”.

Their arguments echo other academics, such as Bruce Hood, professor of developmental psychology at the University of Bristol, who has warned schools against using “neuroscience nonsense” in the classroom.