- Home

- FE leadership stress: what can research tell us?

FE leadership stress: what can research tell us?

It’s time to talk about stress. But before we get on to how it’s caused and what can be done to counteract it, there’s a crucial factor that needs addressing.

Many college leaders will say they suffer from stress. But the reality is that many suffer from distress - a type of stress that damages us as individuals.

I’ve been a senior leader in further education for the past 20 years - six (and still counting) of which have been as a chief executive. I’ve witnessed masses of senior colleagues around the sector in distress, caused by the constant, unrelenting, long-term pressure of working in leadership positions within FE. I, too, have experienced years of distress and being under pressure - and I was forced to find positive coping strategies to survive and occasionally thrive under prolonged impacts of pressure.

Opinion: Why college leaders must learn to embrace failure

Tes FE Podcast: The FE leadership challenge

More: 6 secrets to being a great college leader

When looking for coping strategies, I turned to research, looking for tried-and-tested methods. But actually, there is so much written about stress that ignores the basic academic evidence and the truths behind the suffering - and worse still, there is almost a total absence of research into leadership stress in FE.

Leadership stress in FE

But based on what’s available, what can we learn about chief executive stress - and how to cope with it - from research?

To begin with, it might be helpful to define stress a little more clearly. The working definition from Lazerus in the 1960s suggests that stress is “an interaction and the relationship between individuals and their environments”. He also went on to say that it was a “consequence of those interactions”. In essence, often it is what happens after an interaction, and how we think of that experience, that affects our ability to cope with pressure in the long term.

Pressure performance curve

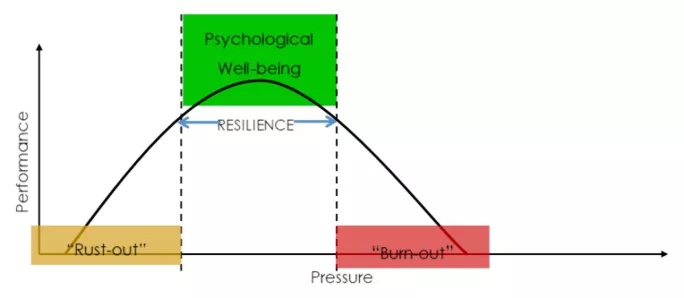

The first coping strategy is the Pressure Performance Curve. It suggests that pressure runs in the form of a curve and everyone sits somewhere on the curve at any one time.

At one end we have “rust-out”, where we have low pressure and low performance because there is nothing to get us excited. At the other end is burn-out, where we have high pressure but low performance. Somewhere in the middle is a sweet spot that we should aim to secure.

If we think about where we are on this pressure performance curve, it is helpful to, firstly, self-reflect on our own position, and, secondly, to sometimes think about where our teams might be at any given time on that curve.

Using a simple scaling exercise, between one and 10, of where we might be on the curve, is a quick way to test the amount of pressure we might be under at any one point. As a college chief executive, I use this technique frequently with good effect and it might be worth trying with the teams that you lead.

The stress bucket

The “stress bucket” is a really simple model and has become the mainstay of mental health first-aid teaching. It’s a helpful tool to use with staff, students, and ourselves, alike, and a quick way of understanding how distress can build over a period of time.

Stress flows into the bucket caused by externalities. If it overflows then that becomes the breakpoint. It’s important for us to understand what is filling the bucket up: what are the environmental factors? Is it management? Is it funding pressures? Is it sheer abundance of workload?

Now consider which activities can stop our buckets overflowing. What positive coping strategies can we use? Exercise perhaps, or spending time with family and friends - whatever helps you to alleviate stress, make sure you carve time out of your week for it.

The burn-out checklist

Professor Cary Cooper suggested that time pressures, the demands of work on our private life, the impact of work on relationships with our family, work-related travel and the concept of work overload all lead to burn-out. Combine this with long working hours, inadequately trained people in your team who work for you, and all the stresses and strains to cope with in interpersonal relations, and make a master burn-out checklist. Reflect regularly on how many boxes you tick, and how many of those working for you tick - and if it’s an overwhelming majority, take positive steps to prevent complete burn-out.

A resilience prescription

In 2006 Dennis Charney identified a whole set of factors that would support a reduction of overall levels of stress while developing and building resilient leaders. His work suggests that, as leaders, we should develop a strong sense of purpose and the stronger our personal moral compass, the less likely we are to be affected by the ups and downs of our environment. Leaders should adopt a positive attitude and link to that our ability to use cognitive flexibility - ie, the ability to reframe situations and to think differently. The ability to recognise and develop your own strengths is also important.

Charney also suggested that the magic bullet might be looking after our physical condition and that exercise might be the single biggest factor to allow people to build up resilience over time. Combine this with strong social support networks: having friends, and proactively making use of friendship groups, creates more perspective in our lives.

Not all of those strategies may work for you, but it’s clear that, as leaders, it’s more important than ever to develop a greater understanding about the causes of, and solutions to, distress.

In the long run, it not only allows us to support our own physical and mental health, but also those of our employees and colleagues. When an emergency oxygen mask drops from the ceiling in an aeroplane, it’s crucial that you put on your own before helping others - distress works the same way. And if we don’t model good behaviours relating to coping mechanisms with stress, it’s likely that not only we will suffer, but also the teams that work for us will suffer, too.

Stuart Rimmer is the principal of East Coast College

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters