“Can I have a word?”

These five little words have the power to fill a parent of primary-aged children with dread. Because it’s always bad news when spoken by a teacher at the end of the school day. You see, the after-school chat with a parent is a favourite behaviour management tool among teachers at primary level. Unfortunately, it is a deeply flawed one.

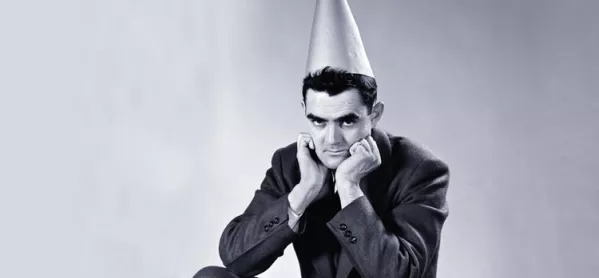

It’s not just the awkwardness of the whole situation, though that makes for a bad start. If the whole playground of waiting parents can’t actually see you being singled out for a chat, it certainly feels like they can as you walk off, away from your car and into the school building with the teacher.

It’s also that the end of the day is a difficult time to have a proper discussion about behaviour issues. Parents have often rushed from work to get to school on time, or are on their way to pick up siblings or attend after-school activities. This means that the opportunity to have a meaningful and constructive discussion about what is happening with your child is missed: you are simply too preoccupied and in urgent need of being elsewhere to really give the conversation your full attention.

This method of “calling out” a parent sets the wrong tone, too. I spoke to one parent who spent much of her son’s Reception year at school cowering at the back of the playground at pick-up time, dreading the teacher walking towards her, which happened several times a week. Her son was often the last one let out, which she knew was a bad sign. After these pick-up time chats with the teacher, she would regularly walk home in tears. She was left feeling responsible for her son’s bad behaviour and wondering what she was doing wrong as a parent.

But what are the alternatives to the playground walk of shame? Is there another way for teachers to reach out to parents when their children’s behaviour has become problematic?

Say it in a letter

Some teachers say that they prefer to talk to parents on the telephone, which means that the parents can usually talk out of earshot of their child and avoid the gauntlet of the playground. But this has its own drawbacks. Parents recall horror stories of receiving phone calls from the teacher during the working day, which meant that they weren’t able to give the teacher their full attention, and they then spent the rest of their time in work worrying. It’s also unlikely that you would candidly discuss your child’s various misdemeanours in your silent, open-plan workplace.

A much better option, according to parents, is actually often seen as a last resort by teachers: the humble letter.

Parents that I spoke to preferred this method of communication, be it emailed or sent traditionally through a book bag, as it gave them a buffer between receiving information and formulating a plan of action and writing a response. They check their email when they are ready to deal with email. They are able to talk about things with their partner, or just consider their response more carefully before replying. It also prevents that initial defensive response dictating the conversation.

Might this method cause a delay in dealing with the issue? All the teachers I spoke to agreed that it was best to let parents know as soon as possible if there were legitimate concerns about their child’s behaviour. They felt that they wanted to get parents on their side and support them to improve things for the child. Yet the speedier methods do not necessarily elicit that supportive response. The letter may be a longer process but it will undoubtedly prove to be the most successful.

Fiona Hughes is a freelance writer based in Devon. She tweets as @superfiona

This is from an article in the 12 February edition of TES. Subscribers can read the full article here. This week’s TES magazine is available in all good newsagents. To download the digital edition, Android users can click here and iOS users can click here

Tell us what you think on TES Community.

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook