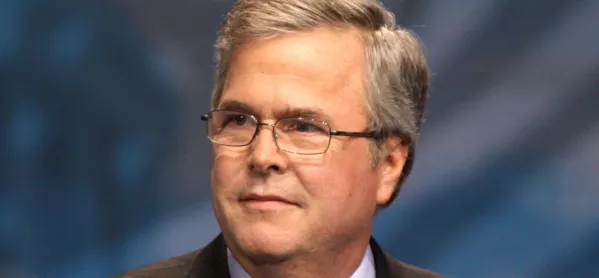

Jeb Bush: the man who would be president skirts issues of education

On his first trip to Iowa as a prospective US presidential candidate, former Florida governor Jeb Bush sidestepped a question about what is supposedly one of his strongest issues: education.

Mr Bush, who is poised to bid for the Republican Party nomination, might have been expected to take credit for his dramatic education reforms in Florida, which include the conservative ideas of letting parents choose their children’s school and paying teachers on the basis of their students’ test scores.

But Mr Bush is vulnerable on another education issue: he has backed the Common Core, a set of nationwide standards opposed by many conservatives, partly because it is seen as an intrusion into local control of schools and partly because it’s supported by Democrat president Barack Obama.

So when he was asked about the Common Core during his recent visit to Iowa - a sparsely populated state that nonetheless enjoys great influence because it’s the first to select the parties’ nominees for president - Mr Bush never referred to the initiative by name, and insisted that he opposed the federal government’s meddling in education.

It was an insight into the complex role education plays in the deep partisan divide that is American politics, and it highlights the irony that one of Mr Bush’s strongest assets in his likely campaign is also one of his biggest liabilities.

“Everybody says they’re for improving education. It ranks behind only motherhood,” says Peter Brown, assistant director of the influential Quinnipiac University Poll and a former Florida political journalist. “But this is the same thing that happened when everybody said they were for reforming healthcare. Then, when they got down to the details, there was a huge difference about what constituted reform.”

A conduit for ambition

Mr Bush announced in December that he was considering running for the Republican presidential nomination.

The son and brother respectively of former presidents George H W and George W Bush, Jeb Bush failed in his first campaign to become governor of Florida in 1994. In the aftermath, he helped to start that state’s first charter school - paid for by taxpayer money but run independently of teachers’ unions - in a predominantly black, low-income section of Miami.

By the time he ran again for governor in 1999, he had a plan to drastically transform Florida’s weak education system, plagued by low graduation rates, a big gap between the achievements of white and non-white students, and some of the nation’s worst 4th grade reading scores.

“Education was a good issue for him because almost everyone cares about it,” says Matthew Corrigan, a professor of political science at the University of North Florida and the author of Conservative Hurricane: how Jeb Bush remade Florida. “And when you’re talking about trying to help those at the lower socio-economic levels, education for conservatives is a lot better way to do that than redistribution of wealth.”

Mr Bush won easily this time, and almost immediately set to work. His “A+ Plan” was based on the principle that competition breeds success. It gave parents vouchers (Mr Bush called them “opportunity scholarships”) to transfer their children from low-performing to high-performing public (and sometimes private) schools of their own choice. And teacher pay and student promotion were tied to the results of annual assessment tests.

The results appeared impressive: 4th grade (aged 9-10) reading scores shot up five times faster than in the country as a whole; only one state improved more quickly. Black and Hispanic students made particular gains, and graduation rates rose from 52.5 per cent in 1999 to 76.1 per cent last year.

“It is just very clear that the reforms under Jeb Bush led to pretty dramatic gains,” says Marcus Winters, a professor at the University of Colorado College of Education.

By 2011, these accomplishments were being noted even by Mr Obama. “We are so grateful to him for the work that he’s doing on behalf of education,” the president said at an event in Miami.

‘Gaming’ the system?

Florida’s successes have not gone entirely unchallenged. Some researchers point out that the policy of holding back students in the 3rd grade based on assessment test scores artificially inflated the reading results of 4th graders.

“The miracle was a fraud, basically,” says Walter Haney, senior research associate at Boston College’s Center for the Study of Testing, Evaluation and Educational Policy. “There are all kinds of strategies to game the system to make test score averages seem to improve without actually benefiting students.”

And while they applaud Mr Bush’s attention to the achievement gap between white and ethnic minority students, Florida teachers resent that they were shut out of the reform process.

“It’s been done with almost no concern for what classroom teachers, education researchers, even elected school boards have to say,” says Mark Pudlow, spokesman for the Florida Education Association teachers’ union.

There has also been extensive criticism of diverting taxpayer money, through those vouchers, into private schools, including some religious schools. Mr Bush’s “opportunity scholarships” were blocked by the Florida Supreme Court in 2006, partly on the grounds that they violated the constitutional separation of church and state.

So, privately educated Mr Bush, who also sent his own children to private schools, got around the problem by instead letting -private corporations put money directly into scholarship funds to pay for student vouchers - and knocking the same amount of money off their tax bills. Florida’s voucher programme is now the biggest in the US, and this year sent nearly 70,000 students to private schools.

Legacy of charter schools

The extent to which the private sector has become involved in education in Florida has been particularly controversial. Many of the charter schools are run by non-profit corporations set up by private companies - often residential developers who see the schools as inducements that can help them to sell houses - or are run under contract by private companies.

Under Mr Bush’s tenure, the number of charter schools in Florida exploded from one to 651, collectively educating more than 250,000 students. Not coincidentally, say critics, this has weakened the teachers’ union, a mainstay of the Democratic Party, since charter schools are not subject to collective bargaining.

Unlike public schools, charter schools can be selective about which students they admit, making direct comparisons difficult. They enrol more non-white students than traditional public schools, for instance, but fewer from low-income backgrounds or with special needs.

Students in charter schools score higher on standardised tests of reading and slightly higher in maths and science, according to the Florida Department of Education, and the gap between white and non-white students is narrower.

Such results gave rise to a new national organisation that Mr Bush founded after he left office in 2007, called Excellence in Education, which encourages the spread of his ideas.

“The thing I think he doesn’t get enough credit for is how much the Florida reforms spurred the modern educational reform movement,” Professor Winters says.

But Mr Bush’s support for the Common Core threatens to come back to bite him. As well as now avoiding saying the words “Common Core”, Mr Bush has endorsed a Senate measure discouraging the federal government from creating incentives to encourage states to adopt the standards.

Meanwhile, in Florida, the teachers’ union and other groups have filed yet another lawsuit to block the voucher programme, and the new governor and legislator are taking steps to eliminate some of the many assessment tests Mr Bush put in place. “That was a major part of his agenda,” says Professor Corrigan. “If some of it gets rolled back, then he’s got less to talk about.”

To read more, get the 5 June edition of TES on your tablet or phone, or by downloading the TES Reader app for Android or iOS. Or pick it up at all good newsagents.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters