- Home

- Why we can’t assume every student welcomes a Biden win

Why we can’t assume every student welcomes a Biden win

The day after the 2010 UK election, I printed out a picture of the newly elected MP and pinned it to the sixth-form notice board.

The school’s constituency had swung from Labour to Tory, and I thought it important that our students be able to recognise their new MP.

The head of sixth form came in 20 minutes later, saw the picture and ripped it down.

She would not have known that I’d put it there, so I didn’t take it personally. But I was struck by how partisan this action was.

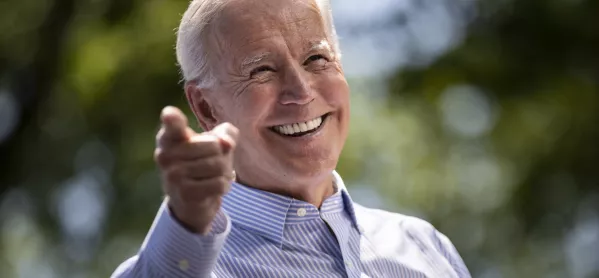

Celebrating the defeat of Donald Trump

Fast-forward to 2020 and I found myself in a discussion with a colleague, who told me that it was his “moral duty” to tell students about his political views regarding the US presidential race.

It was clear that he saw it as a moral duty because he was certain he was morally correct.

I have no problem with teachers talking about their own political convictions, but I think we have a much more important task in front of us than simply telling students what we think.

That is, to foster in students a desire to find out why people hold views that are different to theirs.

The thing is, it’s much too easy to follow Hillary Clinton’s mistake of putting all those whom we disagree with into a “basket of deplorables”. And this really is a mistake. It causes harm because it demonises the other.

That’s never a good thing, even if you’re doing it because you’re certain you are morally superior.

Why is Joe Biden the right choice?

So, if you think Donald Trump is a bad person, the question is, why did 70 million people in the USA vote for him to be president?

It’s just not good enough to write them off as stupid, bad or brain-washed.

If you were a passionate Remainer in the Brexit debate, the question becomes, why are so many people in the UK pro-Brexit? Calling them out as uneducated, old or racist is too lazy.

If you think Boris Johnson is a buffoon, why did he win such a strong majority at the last election, with support from many people who had previously been staunch Labour supporters?

As teachers, we need to be asking these questions ourselves and bringing our students with us on this journey.

Model reasoned debate

We need to model the practice of being brave enough to ask people we vehemently disagree with why they think the way they do, without writing them off.

Apart from anything else, this is a student wellbeing issue. Demonising people who disagree with us creates demons. Young people have enough to deal with - they don’t need those of a different political persuasion turned into hordes of fantasy monsters.

Also, creating an atmosphere where only some political views are acceptable is obviously going to alienate some young people.

I often play devil’s advocate in class discussions that touch on politics and I am routinely surprised that, when I do, there’s much more of a variety of opinion than was first apparent.

The bubble of acceptable groupthink needs to be punctured to let every student express themselves.

It also needs to be punctured in order to allow every student to think about and articulate the reason why they hold the views that they do.

Explain your reasoning

Often, I find simply asking a student why they think a certain way politically is met with surprise because they’ve never actually been asked to justify it before.

They’ve grown used to the idea that it’s simply a fact - it’s the correct way to think - everyone they speak to thinks the same way, and everyone who doesn’t think that way is wrong and bad.

That’s a problem because, if you don’t get a chance to think through your arguments, and you’re suddenly confronted with someone who disagrees with you, you’re much more likely to find you don’t have the killer arguments you thought you did.

That, in turn, leads to emotions such as frustration and anger because you know you’re right but you don’t know exactly how to communicate your rightness.

Surely, we want to develop students who are confident and articulate in their beliefs, whichever point on the political spectrum these beliefs might come from?

Avoiding anarchy

None of this is a purely academic exercise either.

Moral certainty without reasoned debate leads to people who are happy to trample over others in pursuit of their moral utopia, without seeing the irony: they know they are right even if they cannot articulate why they are, or find space to accept another point of view.

This leads to fear of other people, and other ideas, which, in turn, leads to anger.

This can have profound - and often highly destructive - consequences.

That is something definitely worth avoiding, whatever political persuasion you may have.

Aidan Harvey-Craig is a psychology teacher and student counsellor at an international school in Malawi. His book, 18 Wellbeing Hacks for Students: using psychology’s secrets to survive and thrive, is out now. He tweets @psychologyhack

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters