‘Language exams, originally constructed to be more attractive to potential candidates, are now driving the best away’

A couple of years ago, the director of the RSC sat the A2 English paper on Shakespeare. I think he scraped a B.

Many colleagues will have experienced the frustration and disappointment we feel when some of our brightest and best pupils fail to achieve their predicted grades. These poor results are seen by pupils, parents and senior management as failures, and have disastrous consequences for university applications, not to mention confidence in ourselves and the system.

The well-heeled can ask for a re-mark or even appeal, but the costly process appears just as arbitrary in its outcome as the initial result. Further enquiries to the exam boards generally yield the helpful advice from the examination boards to “refer to the criteria”.

The criteria purport to be objective and to lend themselves to the quantifiable as readily as do those of maths or science. A top grade should be within the reach of a non-native speaker. Nevertheless, when assessing Camus or Schlink, two examiners are bound to have different ideas about what constitutes satisfactory or excellent understanding of the text.

Following on from last year’s conference at Dulwich College on subjectively severe/unfair grading at AS and A-level, there seemed no better method of testing the system this summer than to enter the examination alongside the pupils I had taught. If, after over 30 years of teaching French and German at all levels (including IB Language A), I could not apply the criteria correctly and achieve a top grade, what chance would my pupils stand?

To cut a long story short, the German was fine, the French was not.

I approached both the French and German papers with equal seriousness. I went to bed early the previous evening. I did not whizz through the questions and leave the examination room early. I took sips of water at regular intervals. I planned each response clearly, wrote on alternate lines and in my neatest handwriting. Everything was arranged to make the markers’ job logistically easy. My script was “accessible”. I confess to the odd slip in the heat of the moment. I forgot the second accent on “événement” in the prose. I wrote “Sie sagte, daß…” instead of “dass”. I gave the exercise my best shot.

In the German research-based essay, I linked the historical theme of “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” in der Vorleser to issues wider than the Second World War, such as social attitudes and legal questions that have arisen since reunification. This seemed to go down quite well.

By way of contrast, in French, my linking of lethal violence in L’Etranger with Daru’s rage against “la folie des hommes” in L’Hôte was less successful. Admittedly this paragraph was quite brief, as the limit of 270 words must be respected. In the rest of the essay there was, nevertheless, extensive quotation from, and analysis of, a specific, significant episode from the longer work. The mark I achieved was just one point better than “Adequate understanding; some evidence of reading and research.” Obviously, I had failed to demonstrate any trace of “Clear evidence of reading and in-depth research” (my emphasis). Hmmm. Evidently, I am a beta minus man and lucky still to have a job.

The re-mark brought about no changes. A copy of my paper was requested and then assessed by the rest of the department at Fettes, along with heads of department from other schools. The response can be summed up as follows: even allowing for some degree of subjectivity in reading, research and understanding, the mark achieved for quality of language and organisation and development in French was ridiculous. God help our students!

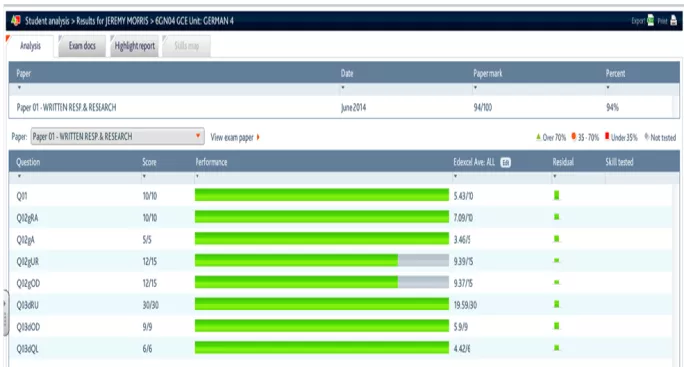

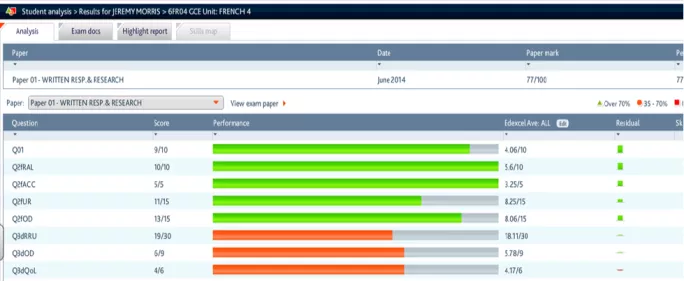

The marks I received are given below.

The irony of the situation is that an examination, originally constructed to be more attractive to potential candidates, seem to be driving the best away. Among those who do persevere with languages, some very weak pupils have achieved quite respectable grades, far surpassing expectations, so perhaps we should not carp too loudly. However, the perceived reluctance to award the top grades (which so many universities require) is a factor that prompts our ablest pupils to opt for subjects with more predictably successful outcomes.

Fortunately, Oxbridge entry depends far more on performance at interview and in-house language tests than the elusive A*. Let us hope that other universities adopt an equally benign (enlightened?) approach, at least in modern languages, and that the current decline in entries can be halted.

And the consequence of this particular tale? I have not been sacked for incompetence; indeed, I have just applied for a job as an A-level examiner when I retire next year.

Jeremy Morris is former head of languages at Fettes College

To read more, get the 22 May edition of TES on your tablet or phone, or by downloading the TES Reader app for Android or iOS. Or pick it up at all good newsagents.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters