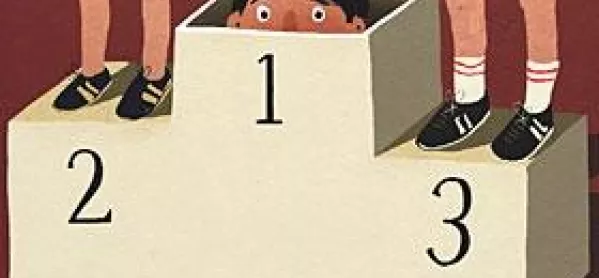

Myth: ‘State schools see sports as elitist’

Original paper headline: Myth: `Competitive sports and setting are frowned on in state schools as elitist’ The belief that state education is driven by a widespread “all must have prizes” philosophy is both persistent and ill-founded. Critics of modern schools often cite opposition to competitive sports and support for mixed-ability teaching in all subjects as prime examples of this view. Nor are these claims new. A decade ago The Times said “the decline in competitive sport in state schools” was the result of “aggressive political correctness”. In 2004, the author Ferdinand Mount claimed comprehensive education was imbued with “a different ethos . hostile to competitive sport”. The same year, Dr Andrew Cunningham stated that “for too long there has been the view amongst experts that team sports are wrong”. London’s selection to host the 2012 Olympics led Alyson Rudd to write in The Times, “I expect schools to change, to allow in the competitive streak that they have been trying to eradicate.” And at the recent Conservative conference, Michael Gove, shadow education secretary, praised one school that played “proper competitive sports” as if all but unique. Yet as early as 1987, the Thatcher government commissioned an inquiry into the issue, which found no evidence of “any philosophy that is against competition”. Two years later The Times discovered only one of 60 Labour- controlled education authorities - Sheffield - opposed competitive games, and even this was ambiguous. The authority’s PE adviser said that although many primary children were too young for full-side team sports, “it was not their policy to discourage competition in schools” and certainly not team games in secondary schools. In more than 40 years working in and with state schools across England, I have never met a single head, teacher, governor, inspector or officer who opposed competitive sport. I have asked council members of the Association of School and College Leaders, who collectively have decades of experience in schools, about the issue. Again, none had ever even met such views, let alone held them. If there has been a decline in competitive sport (and if so, it has been grossly exaggerated) it has nothing to do with ideology. The reasons are more complex, including pressure created by academic league tables and the national curriculum, and the number of teenagers working after school and on Saturdays. Yet, despite such constraints, the range of extra-curricular sporting activities in state schools is far wider than in the past. At school in the 1950s, I played only soccer in the winter and cricket in the summer. Although a sports day was held, athletics featured little. In contrast to this thin diet, the mixed school where I was head offered soccer, rugby, hockey, netball, tennis, swimming, badminton, basketball, cricket, athletics and dance. Schools across the country, both primary and secondary, continue to play competitive fixtures against other schools in many sports. In September 2008, the Daily Mail appalled its readers with news that 438 schools no longer held an annual sports day - or, as a non- Mail reader might put it, 2 per cent. Equally nonsensical is the claim that state schools are ideologically wedded to mixed-ability teaching. Like most heads, I approached this issue pragmatically. While I favour setting, it has pitfalls: the threat of low teacher expectations of pupils, children being misplaced, or easy assumptions that setting removes any need to differentiate. Yet such caveats hardly justify Daily Mail writer Melanie Phillips saying that the original intention to preserve setting “lost out to mixed-ability classes”, or former chief inspector of schools Chris Woodhead’s claim that a genuine comprehensive would not contemplate setting or streaming. The research of educationalist Caroline Benn, based on HMI reports, showed that even in 1968 only 4 per cent of comprehensive schools organised teaching on fully mixed-ability lines. In the mid-1970s, HMI found only 2 per cent of comprehensive schools had mixed-ability classes in all five years, and even in London the figure was only 7 per cent. Studies in the 1980s found 80 per cent of comprehensive schools set for maths after the first year and 93 per cent after the second. My own survey of members of the council of the Association of College and School Leaders schools revealed that none had come across a school ideologically opposed to setting by ability. Recent DCSF figures do show that only 45 per cent of comprehensive classes are set, a figure seized on by Michael Gove to demand an end to mixed-ability teaching. This misunderstanding reveals the extent to which ignorance of school organisation can distort educational reporting. Many schools, which have no objection in principle to setting, leave it to the end of Year 7 so they can judge pupils’ ability properly by allowing them time to settle in. This is a valid approach, hardly indicative of over-zealous egalitarianism. Few schools set in PE, technology, art or personal, social and health education. I suspect not many outside schools would expect these to be organised by ability. Certain optional subjects in Years 10 and 11, such as music or a minority language, may throw up only one group, which prevents setting. The 45 per cent figure is not nearly as low as it may first appear, particularly when Year 7 alone might account for a good proportion. Ill-informed columnists on national papers will doubtless continue to portray state-school teachers as left-wing ideologues desperate to prevent the emergence of any new Wayne Rooneys. And politicians of all parties, eager for favourable headlines, will regurgitate such nonsense as if based on the soundest academic research. But nonsense it remains, as thousands of teachers and millions of parents and pupils across the UK well know. Next week “A return to grammar schools would improve standards and social mobility” Gordon Brown used last year’s Olympics to announce that schools should bring back competitive sports and end the “medals for all” culture. His comments surprised heads, nearly all of whom organised sports days, and the 1,500 pupils who travelled to Bristol for the fiercely competitive UK Schools Games. Only winners there gained medals. A 1987 Thatcher government inquiry into the supposed lack of competitive sport in schools found no evidence of “any philosophy that is against competition” and noted that “allegations made are without foundation”. Nick Gibb, shadow schools minister, has criticised schools for failing to set enough lessons by ability. “There’s a big section of the education establishment that regards mixed-ability teaching as an important element of social engineering in our schools, and don’t care whether or not it leads to higher academic standards,” he told the Daily Mail in July.A ban on setting?

The state of sports

Setting the scene

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters