- Home

- An open letter to Nicky Morgan: ‘For the first time in my career, I’m doing things I don’t believe in. I can’t sleepwalk into…

An open letter to Nicky Morgan: ‘For the first time in my career, I’m doing things I don’t believe in. I can’t sleepwalk into this madness’

Dear Ms Morgan and Mr Richardson,

Thank you for your letter dated 11 April 2016. My initial reaction was to question whether this was meant for me, as it didn’t appear to address the concerns I had raised in my earlier letter. The main focus of my letter was the handwriting expectations (something not even mentioned in your response) and the tick-box approach to assessment this year (again, something you failed to comment on). To put it simply, handwriting should not be a deal-breaker, especially with the tick-box approach, allowing no room for error.

I would like to apologise if the point of my letter was unclear. I hope to clarify it here, through addressing some of the comments you made in your response.

Before I begin, I want to make you aware that I am all about high expectations. You don’t lead in an outstanding inner-city primary school without them. It’s important that you keep that at the forefront of your mind while reading this letter.

Identify the subjunctive

In your response, you highlight that “in order to read and write, children must also learn how to spell and gain an understanding of grammar and punctuation”.

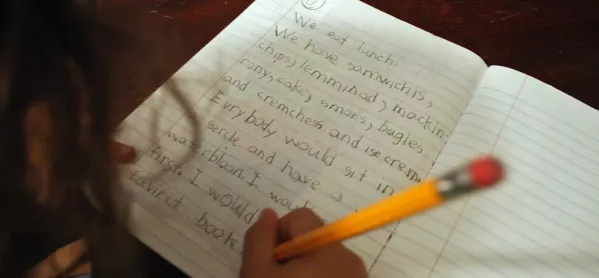

I am in complete agreement that spelling is important. I am well aware that there is a link between spelling and reading. I would assume, however, that research which highlights these links is based on children older than 7, as these children are further along in their journey to becoming a writer. It’s important that we remember that learning to write is a long and exciting journey. I also believe that an understanding of grammar to improve children’s composition is important. Teaching children to underline word classes and identify the subjunctive form does not improve the composition of children’s writing.

Let’s take a closer look at spelling. The problem I have is that the expectations of the interim framework are out of step with the developmental stages that children go through when learning to spell (assuming the children do not have dyslexia, dyspraxia or English as an additional language, which many, many children in this country do). Please could you tell me how the spelling lists were created, and what research their creation was based on?

Eating steak to improve your iron count

Learning to spell is highly complex and there are many different rules for children to learn. Throw in the fact that a lot of words in the English language are not phonetically decodable and the myriad of exceptions to the rules, and you are left with a situation in which the best strategy for children to learn to spell is through exposure during reading and through repetition in context in their writing. We’re not talking a few times here; we are talking about the children using these words over and over again, over a number of years.

Now let’s take a look at some of the “common exception words” that seven-year-olds are expected to learn. “Steak”, “Christmas” and “improve”, all appear on this list. Are these words that seven-year-olds are going to be using frequently in their writing? I very much doubt it. Are they able, then, to use these repeatedly in context? Absolutely not. What impact do you think this has on their ability to learn these spellings? This leaves teachers with one option: engineer opportunities to get these words into children’s narratives. That’s not right.

Spelling and handwriting make up 58 per cent of the statements for the expected standard. The rest is about grammar and punctuation. The total lack of text-level objectives on the interim framework for seven-year-olds means I am able to assess a piece of writing against the criteria without being able to tell you what the piece of writing is about, or even what genre it is. That’s not right.

This narrow focus on elements of writing that should come at the end of a child’s journey to be a writer (not the beginning) means that in classrooms across the country the joy is being sucked out of writing. Children are underlining adverbs rather than choosing precise adverbs for impact. Teachers are engineering opportunities for children to write commands in their narratives. Dictations about “eating steak to improve your iron count over Christmas” are commonplace. Teachers are working their socks off to get children to a standard that is unachievable and misses the point of what it means to be a successful writer. For the first time in my career, I am doing things I don’t believe in. Remember, I’m all about high expectations, but I’d be mad to expect a five-week-old baby to walk.

Rewiring children’s brains

You appear to justify these unachievable expectations in your response by highlighting that “as a result of our ambitious reforms over the last Parliament, and the hard work of teachers and leaders, English schools are now better than ever before”.

This may well be the case, but this year is going to be very, very different.

The majority of schools will not achieve well in the key stage 1 and key stage 2 Sats. I can say that with some confidence, as a leader of a school that consistently performs in the top 10 per cent nationally. However, we’re currently struggling to reach these arbitrary goal posts, so I can assume that at least 90 per cent of all other schools are struggling too (unless they’ve found the key to rewiring children’s brains to enable them to master things they are not developmentally ready to).

In Year 6, children are being tested on six years of curriculum content, when they have only experienced that curriculum for two years. Not only is this unfair on those children (and won’t be fair until the current Year 1 children are taking their Sats in five years’ time), but it’s also not going to provide an accurate reflection of the “ambitious reforms” that you talk of.

However, it’s not as simple as that, is it? As you know, the ultimate decision as to whether children are at the expected standard or not will not be taken against a set of criteria, but against a score that the government decides on once it has an idea of how everyone has done. We can assume then, that the pass mark will be quite low, in order to keep this upward trajectory that you talk of; therefore everything will turn out OK in the end. Everyone will wonder what all the fuss was about and it will be proof that schools are entrenched in low expectations and that the children could do it all along.

Alternatively, to fit with the government’s “high expectations”, and in line with the interim framework, the percentage of children reaching the expected standard could be low if the pass marks are high. Either way, it will be used to argue that low expectations are rife in primary schools. We’re in between a rock and a hard place and it’s all a hideous distraction from our core business of educating children. That’s not right.

Albatrosses around teachers’ necks

As I’m sure you are aware, there is currently a recruitment crisis. It has been said recently that leaders must be more positive about the profession in order to combat this crisis. Whatever you take away from this letter, it cannot be that I am a leader who is negative about our profession. It’s not the profession I am negative about, but the poorly thought-out albatrosses around all of our necks at the moment.

School leaders are being micromanaged to within an inch of their lives. I cannot sleepwalk into this madness without expressing my concerns and frustrations. And let’s not kid ourselves that converting to an academy will solve this by increasing our autonomy. As long as these assessments exist, so will an ill-conceived, out-of-touch, narrow curriculum. My points are based on research and experience and are driven by a passion for education and improving life chances for children, not by a desire to berate the profession. We want the same thing, but the government must slow down, take a deep breath, listen and do what’s right, however long that takes.

I am left with a shred of hope from your closing statement: “We will continue to listen carefully to what teachers tell us, and do whatever we can to support them in doing their jobs.” You imply in your letter that the best way to have your voice heard is through participating in consultations. I don’t recall there being one about this approach to assessment. However, the fact that this is an interim framework implies that it is up for discussion and debate.

I am asking you to do the right thing and open up a consultation on the end-of-key-stage assessments to enable us, together, to begin the journey towards getting it right for the children.

Thank you for taking the time to read this letter. I look forward to your response.

Kim Clark

Kim Clark is deputy headteacher at Fairlawn Primary

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters