“I have learnt silence from the talkative, toleration from the intolerant, and kindness from the unkind; yet strange, I am ungrateful to these teachers”. So said Khalil Gibran, in Sand and Foam (1926). To be sure, much of what we learn at school is unintended, the product of often accidental or egregious interactions.

When students engage with the authority structures of school, rather than with each other, the results can be equally unintended and no less consequential.

In the 1970s Paul Willis undertook an ethnographic study of a group of working-class school-children in Birmingham. His 1977 book, Learning to Labour: how working class kids get working class jobs became a classic, and served as an exemplar for Tony Giddens’s theory of structuration showing how “strategic conduct” won small victories, but worked against the ultimate interests of the actors involved.

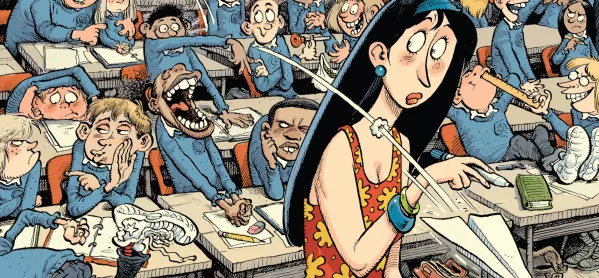

The “lads” who felt marginalised and written off by school chose rebellion. Messing about and subverting authority served a short-term purpose in giving them a sense of control. But by consciously opting out of the school norms, they ended up leaving without qualifications, consigning themselves to a low-skill, low-income future, and actually serving the structural need of the capitalist economy for unskilled workers.

Boys behaving badly is one thing; girls behaving well is surely quite another.

In her 2016 memoir, Respectable, Lynsey Hanley added a gender dimension. The same power dynamics were at work when she was at school, but girls were expected to behave better and work within rather than against the authority of the school. Female students had the additional job of moderating the behaviour of the boys. This is not to say that there aren’t girls who lark about - just that teachers and peers saw disruptive girls as signifying a double disobedience, against both school and gender expectations.

Where does that leave girls who respect and work within prevailing authority structures? Prima facie, this strategy brings success. Compliance and conscientiousness are a substantial factor in girls’ success in examinations - leading to suggestions that the system is now stacked in favour of females.

But compliance has its downside. Whitney Johnson and Tara Mohr argue that women need to realise that work and school operate by different rules: “The very skills that propel women to the top of the class in school are earning us middle-of-the-pack marks in the workplace.” Rule-following and risk aversion do not seem to ease career progression. Johnson and Mohr advocate a less conformist approach at school, urging girls to figure out how to challenge authority; to prepare, but also learn to improvise; to find effective forms of self-promotion, and to go for being respected, not just liked.

Student strategies for survival and success may not travel well beyond the school gates. Schools exist to prepare young people for the world, not just for the next set of exams. That means giving students space to question as well as conform. We certainly need to engage those who feel instinctively alienated from school; but we mustn’t lose sight of those who seem to fit in all too well.