- Home

- Schools should have dedicated ‘reading time’ that encourages eclectic choices

Schools should have dedicated ‘reading time’ that encourages eclectic choices

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Pirls) results have been celebrated as a turning point for literacy attainment in England and hailed by the government and parts of the media as a victory for phonics. This is a marked change from the recent Programme for International Student Assessment rankings that exposed some of the stubborn challenges we were facing.

Can this improvement really be solely attributed to phonics? The Pirls test examines how pupils read, comprehend and interpret information. Other factors, such as dedicated reading time in schools and appropriate reading challenge of books, have been shown in our research to facilitate better comprehension skills.

But that’s not to say, as a nation, we’re now set to be propelled up the global rankings. The truth is we still have further to go. Despite an improvement in standards, it is still only a modest improvement. More than that, when you look closely at the results, there is further cause for concern. Of the 50 countries that took part, England had the lowest ranking of any English-speaking country for pupil enjoyment of reading and the lowest-ranking English-speaking country, with the exception of Australia, for pupil engagement in reading.

These findings reveal one of the major hurdles to improvement of reading standards in this country: the notable lack of a ‘reading culture’ in our schools and homes.

Unfortunately, building a reading culture does not happen overnight, nor is it something that you can impose. It should happen organically - but that doesn’t mean that we can’t act to cultivate a culture in our schools.

One of the clear takeaways from the Pirls results was that English pupils are better at absorbing fiction than fact. We need to foster a reading culture that accepts fiction and non-fiction on equal terms. Both have educational merit, from English, to history, to maths; literary skills are invoked in practically every educational discipline.

Beyond the crossover between literary skills and non-fiction, there is also a cultural benefit from promoting non-fiction reads. Renaissance recently conducted a study of nearly 1 million young people’s reading habits across 3,897 schools, in partnership with the University of Dundee, which showed boys take a greater interest in non-fiction than girls, but that they read less thoroughly; this is contributing to poorer educational outcomes.

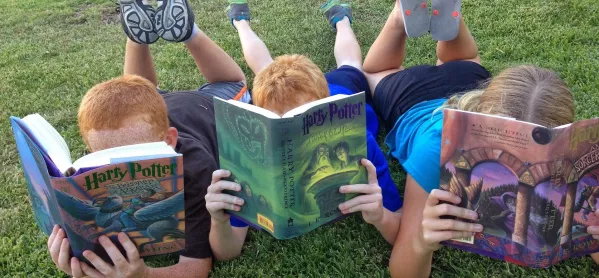

Accepting non-fiction into the selection of books to read in schools would make for a more inclusive reading culture, and one that takes non-fiction seriously. Our only concern should be encouraging children to read challenging-enough books, and getting them to read them frequently and thoroughly - whether fiction or non-fiction. Dedicated reading time can help with this.

Dedicated reading time in schools would help to normalise reading for children. Reading needn’t and shouldn’t feel like a chore. Yet, statistics show that this may well be the reality for children. The recent Read On. Get On. (ROGO) report published by the National Literacy Trust, on behalf of the ROGO coalition of 12 education charities, analysed nationwide government and commercial data (including that of Renaissance). It found that children’s reading enjoyment and frequency of reading is markedly lagging behind their reading skills.

It also showed that children’s reading skills have remained consistent over the past three years - and that girls continue to outperform boys.

It’s not just a gender issue either. Pupils should be encouraged to read at all stages of their time at school, and to push themselves to sustain a higher level of challenge in their reading, but especially on transfer to secondary school. Our research with the University of Dundee shows that problems in literacy, like the disparity in literacy rates between boys and girls, tend to become more acute on entry at secondary school. In bringing in a dedicated reading time at all levels of school, teachers and librarians would provide the necessary support in recommending appropriate reading tailored to a student’s age, ability and interests.

Perhaps because it is a long-term effort, reading culture is something that is often overlooked by educationalists - but all the evidence shows that it is fundamental to improving standards.

If you build a reading culture in schools, you have a self-perpetuating means of improving literacy standards. Children seek books out themselves, get into the habit of reading, and try to tackle different, new and interesting things. Fact or fiction, both contribute to children’s development.

While the Pirls results have been a welcome silver lining to the cloud that has been looming on the horizon for some time, there is still a long way to go. Our schools can be the drivers of positive change; a dedicated reading time that encourages eclectic choices would certainly be a good place to start.

Dirk Foch is managing director of Renaissance Learning UK

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters